“Art functions by creating highly visible exceptions to the status quo,” Renzo Martens writes, “placing love, critique, and singularity outside the circle of exploitation and violence. […] While war and economic segregation pay the bills, love, critique, and singularity are reserved for the audiences of the white cube. Providing this exception for an audience that already lives the beautiful exception is not critical; it is make belief. Illusionism.” (quoted from: Renzo Martens: Art for the Post-Plantation, in: Critique in Practice: Renzo Martens’ Episode III: Enjoy Poverty, ed. Anthony Downey, Sternberg Press, 2019, p. 330)

The world of the photobook is not one we associate with the white cube — photobooks are typically enjoyed in the privacy of one’s home. Yet it is not hard to think of a photobooks bringing the white-cube mindset to people’s homes, one book at a time. We might replace a few words in Martens’ statement — “photobooks” for “art,” say, to arrive at a valid and searing indictment of much of what ills the world of the photobook as well.

Most photobooks dabble in illusionism.

This illusionism is caked into the larger world of art, of which photoland has become a niche. Things are said and shown one way, yet they really mean something entirely different when seen in the contexts in which they are made to appear.

The very first advertising in the most recent edition of Aperture‘s magazine (#245), a colourful double-page spread, presents Gucci, the luxury fashion house. Assorted other luxury brands (incl. Leica) follow. So when viewers then see a photograph by William Camargo entitled We Gonna Have to Move Out Soon Fam! (Anaheim, 2019), showing a person holding a large sign that says “THIS AREA WILL GENTRIFY SOON”, what are they supposed to make of it?

Of course, this is a Gedankenexperiment on my part, because the ads don’t target the likes of me who begrudgingly shop at Walmart, given their limited economic options.

What does the latter have to do with the former? Martens explains: “If art takes responsibility for its entanglement with circuits of capital and exploitation, then it goes beyond the production and display of mere images.” (ibid.)

If.

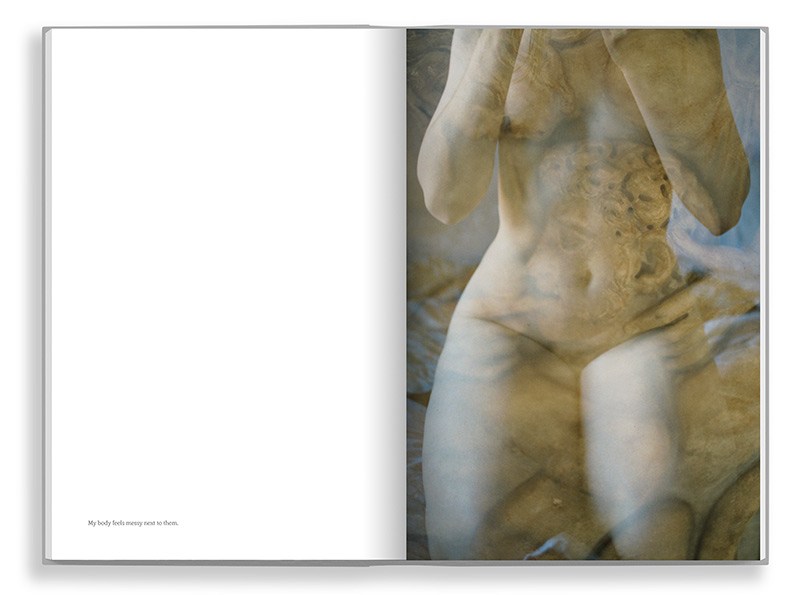

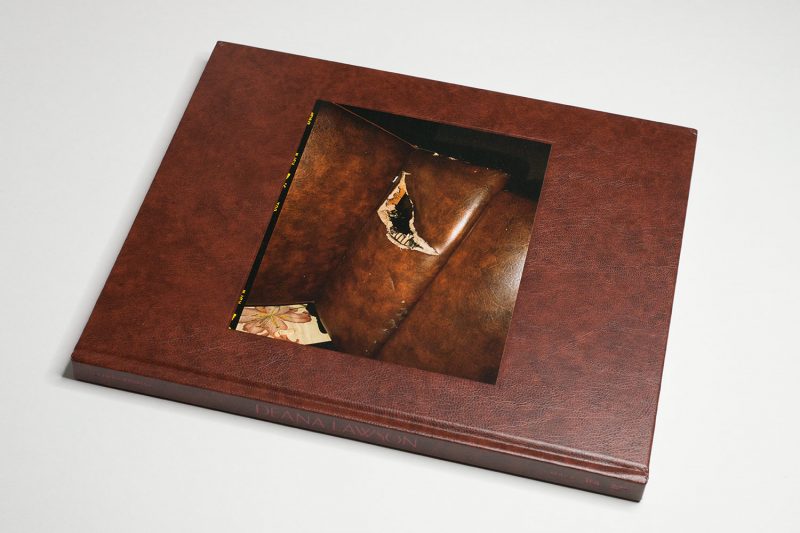

How would you go about your “entanglement with circuits of capital and exploitation”? For sure, it’s not by making photobooks with over one thousand images that sell for hundreds of dollars or Euros, that, in other words, are luxury objects themselves.

“The photobook world is in danger of imploding,” Russet Lederman told me a little while ago, “It’s a niche community and very insular.” If photographers and publishers make books for other photographers and wealthy collectors, but not for the people who find themselves in the pictures, then it seems obvious that we’re facing a very serious problem.

In fact, the problem is widely acknowledged by photographers and publishers themselves, given that the market for these books is stagnant at best. But it’s just so hard to get out of the white cube.

Or is it?

After Poland’s far-right government managed to hijack the country’s Constitutional Tribunal, said Tribunal ruled that existing abortion laws were unconstitutional, essentially outlawing abortion (this might sound familiar to Americans who are seeing this play out right now). Thousands of Polish people had already taken to the street in support of women’s reproductive rights; after the ruling, the country erupted in mass protests on a scale previously unseen.

A group of photographers, researchers, and activists got together to funnel their individual work into something larger: they named it the Archive of Public Protests (APP). Here are their names: Michał Adamski, Marta Bogdańska, Karolina Gembara, Łukasz Głowala, Agata Kubis, Michalina Kuczyńska, Marcin Kruk, Adam Lach, Alicja Lesiak, Rafał Milach, Joanna Musiał, Chris Niedenthal, Wojtek Radwański, Bartek Sadowski, Paweł Starzec, Karolina Sobel, Grzegorz Wełnicki, Dawid Zieliński.

On the website (and on social-media channels), their work is disseminated as a group effort. Furthermore, they produced a number of newspapers, all of which are available for download from the website (most of them are only in Polish; full disclosure: I contributed minor copy editing and translation services to the most recent issue). With very limited financial resources (some minor grants, some crowdfunding, some support from NGOs), the newspapers were produced and then distributed at the very locations where new visual material was being produced: at sites of demonstrations.

In addition to photographs, the newspapers feature slogans often seen at demonstrations; they’re designed in such a way that someone can take the newspaper apart and use a page as a banner at a demonstration. APP have gone out of their way to bring the newspapers to smaller Polish cities, deliberately reaching out of the Warsaw photo bubble.

“My photo book of the year is a protest choice,” writes Rob Hornstra, referring to APP’s work, “both within the world of photobooks and in the country where the work is made. My photobook of the year is a free newspaper.” Alas, on a bookseller’s website a free newspaper isn’t any good: “photo-eye and any photobook store cannot run a business by distributing free newspapers”. And so the newspapers didn’t make this list or any other (unless I missed it — entirely possible, given there now are dozens and dozens of them).

And neither did the 18 Polish photographers, researchers, and activists make the shortlists of the two major corporate photo prizes (one of those oversized tomes for wealthy collectors did, though). At least, they found recognition locally, in their native Poland, where thankfully their work is being recognized. Make sure to head over to Zachęta Online Magazine to see their faces and read their words.

If the Archive of Public Protests can teach us something beyond what it means to be a well-engaged citizen who embraces solidarity with others, then it’s that photoland’s illusionism is a choice and that rejecting it is an option, however arduous this might end up being (especially when faced with a relative paucity of resources — here is a related read: why does success have a paywall?).

The white cube might offer the comfort of a shared make belief. But in light of the increasing challenges faced by our societies, that’s just not good enough any longer — if (there’s that word again) we want to also maintain the comfort of the freedom that we currently still enjoy.

If that’s not enough of an incentive for you to break out of the niche community’s insularity, then go and ask any of the 18 Polish artists what it feels like to have a far-right government systematically trash civic life and the country’s democratic foundation, while taking away basic human rights from the women unfortunate enough to live under its rule and letting refugees starve and freeze to death in a forest.