Given that photography always has one foot in what you could think of as a reality, it often remains at the level of a semi-art. This is especially true in the case of the photographic portrait. I don’t necessarily mean the term “semi-art” in a negative way, because its underlying idea can cut both ways. But historically, because they were aware of photography’s foot in reality, photographers went the extra mile to make their wares look like what they think art ought to look like: this not only involved copying conventions from, say, painting, but also included making huge prints. Pictorialism arose out of this just as much what I ended up calling Neoliberal Realism.

On the other hand, even when photography manages to achieve the level of good art, its underlying nature pulls the viewer back to the fact that what is being depicted is taken from the real world. I suspect that this fact will remain true even once computer-generated images will occupy a space equal to that of camera-based ones: in the end, it’s not how the images were produced, it’s the combination of what they look like and what codes they telegraph that will drive the conversation.

Coming back to the portrait, there are two aspects that no photographer can run away from. There’s the aspect of power. And there’s the history of photography. These two aspects are not completely independent.

Someone has a camera, some other person does not: this sets up one of the most basic problems of photography. The person with the camera has the power. Even though they cannot do whatever they want — the other person might run away, grimace wildly, or try to put their hand in front of the camera, they have all the power over the photograph that goes out into the world. They pick the context in which it might appear, and they’re usually the first to set the parameters of the ensuing discussion around them (especially when photography criticism parrots PR copy).

Per se, this is not necessarily bad. After all, actors do what the script and directors tell them to do. Excepting those cases where actual abuse is happening, nobody has a problem with that. That is their job, to personify another person based on some pre-set parameters. Photographic portraiture can operate along those lines (think fashion or commercial photography).

But usually portrait photography in what’s typically called a fine-art context doesn’t operate this way. Often, photographers come across people they want to take a picture of by chance. Or they seek out a certain type of person. Thus begins the complex negotiation over power that involves question of consent and much more. Large parts are often left unspoken. Photographers know how their cameras operate and what they can do with them. People who aren’t photographers typically only understand this to a limited extent (even when they’re using their smartphones to take pictures).

This relationship is skewed in just the same way that your relationship with your dentist is skewed, or your relationship with your florist, your barber… You get the idea: someone is an expert and has a lot of practical and theoretical knowledge, and the other person decides to trust them (what happens when people don’t rely on that trust is currently playing out in ICUs all over the world).

Practical knowledge means that a photographer knows what the picture will look like in a basic sense. What they don’t know — all the interesting details: that’s what they’re after. Theoretical knowledge means that a photographer is aware of the medium’s history. They know who came before them and what those photographers did. They know — or at least they should know — the full spectrum of their craft, including the conversations that those older pictures have spawned.

As a result, portrait photographers have to deal with a responsibility that is set by their medium: to a certain extent, those that came before you boxed you in. All those portraits that already exist give you a set of constraints to work with — or against.

I’d argue that as a photographer, it’s important to navigate the constraints. To begin with, you’d be in dialogue both with the history of your medium and the conversations people are having right now. But you could also serve as a corrective, as someone who nudges the photographic conversation towards previously uncharted territory. After all, in the arts, constraints can be moved (without that possibility you’re left with mere craft).

In other words, photographic constraints both limit and expand what you can do.

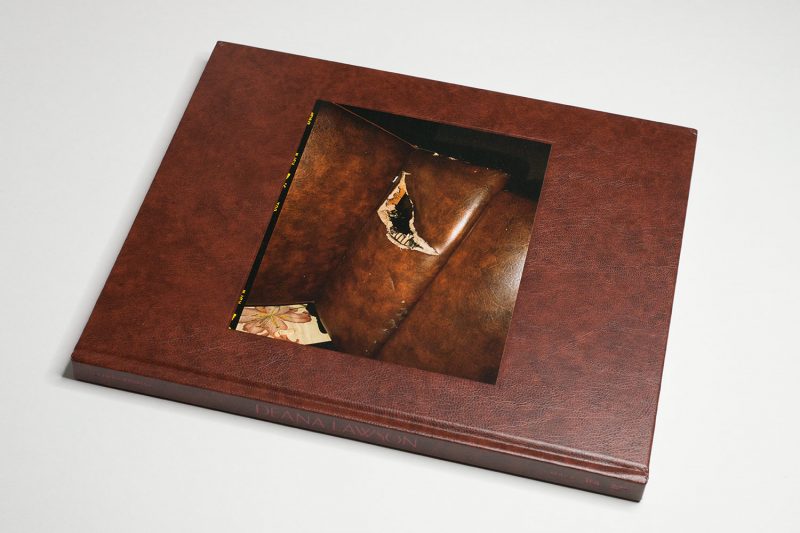

This brings me to Deana Lawson and a new survey of her work. The biographical essay in the book, written by curator Eva Respini, lists a number of artists who served as references for Lawson, some to be expected, some surprising. And yet the artist who is echoed most strongly in these photographs is missing: Chauncey Hare, in particular his photographs of people in their own homes. I sense a similar sensibility at play, even as there are, of course, major differences.

Lawson’s subjects are Black, and the photographs that hold my attention are taken in what look like their homes. Through photographic choices, these homes are transformed into stages that feel at least somewhat alien to the sitter(s). The use of specific poses serves to heighten the drama of the stage, while at the same time giving the sitter(s) power: whatever a viewer might make of their surroundings, the feeling is communicated that the resulting picture is made for the sitter(s), that the picture says something about them — and not the photographer.

But this kind of thinking is a trap. After all, it is widely known how careful Lawson arranges the settings and the poses. I think for someone from the world of photography, this is very obvious. Someone who is not familiar with technical details might simply pick up on what I would describe as the photograph’s artifice: they typically look as if they were designed to look like paintings.

“Deana Lawson’s work is prelapsarian—it comes before the Fall,” Zadie Smith writes in New Yorker magazine, “Her people seem to occupy a higher plane, a kingdom of restored glory, in which diaspora gods can be found wherever you look […] Typically, she photographs her subjects semi-nude or naked, and in cramped domestic spaces, yet they rarely look either vulnerable or confined. […] Outside a Lawson portrait you might be working three jobs, just keeping your head above water, struggling. But inside her frame you are beautiful, imperious, unbroken, unfallen.”

A very different take is provided by In ‘Axis’ and other pieces […], I could not find any of the earned intimacy that pointed to the artist’s own personal experience or long-term communal investment in most of what she was depicting.”

I don’t think these two sentiments are as much in opposition as one might be tempted to think. In fact, I’d argue that aspects of both pervade Lawson’s work. The photographs are aspirational and celebratory. But they operate on a very, very thin line, which easily allows for a read that questions whose aspirations are actually being celebrated here — the photographer’s or her subjects’?

This is not a new discussion in the world of photography. Speaking of the “big-dick energy power dynamics of White male artists” that Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw brings up in her essay (a marvelous phrase that sums up so much!), when Richard Avedon photographed underprivileged people for In the American West, to then showcase massive prints in galleries and museums — what was he actually celebrating there?

I don’t think that past discussions of this topic have been as enlightening as they maybe should have been, in particular since the art world is not very good at dealing with questions of class. This is not surprising, given that the art world’s class composition is very heavily skewed towards the wealthy end.

This is why Chauncey Hare is such an interesting reference. Hare’s approach was a little different. There was no careful staging. What’s more, his interiors turn ever more cavernous through the use of a very wide lens, leaving his sitters often lost and overwhelmed by their surroundings. But I would argue that there is considerable overlap in the underlying idea, namely that it’s a photographer’s task to give dignity to those s/he portrays so that through the picture an audience might come to a deeper understanding of them.

Hare was very open about his political beliefs. In 1979, he staged a one-person protest outside of SFMOMA, objecting to the inclusion of one of his photographs in a show that had been sponsored by Philip Morris. He really wanted people to see underprivileged people in their homes so that there might be some change, and he objected to this goal being pushed with money from the corporation. Obviously, it’s more than unclear whether photographs in a museum can actually achieve that goal, whether it’s sponsored by corporations or not. In fact, he ended up leaving the art world altogether (this article talks about this in detail).

What is more, if you photograph people in their homes with tools they don’t really understand — it’s very obvious from some of Hare’s photographs that some of his subjects never thought they would be in the frame, then it’s a fair question to ask how that gels with your politics: is photographic exploitation any better than the economic one?

I see Lawson as pushing the conversation initiated by Hare forward, while at the same time working toward a similar goal: to make people care about a community that historically has been depicted in very detrimental ways. For both artists, this opens up the same conundrum, namely that given the context the work mostly appears in (museums, books such as this catalogue), Zadie Smith’s read competes with Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw’s.

Looking through the book, I found myself jumping back and forth between these poles. I am a white German man, and I have been thinking a lot about embedded codes in photography. There’s no doubt in my mind that both facts guide my reaction to the work. To focus too much on the artifice of the work runs the risk of missing its point. Still, it is the role that artifice plays in individual pictures that in each case has me tip towards one side or the other.

For the most part, it is the photographs of romantic partners that I find particularly striking. They often include the full spectrum of sexuality in a single picture: an embrace might hint at the tenderness of a first touch as much as at its later carnality. In contrast, pictures like Axis had me wonder about whether the photographer’s aspirations with the picture and the resulting outcome really were aligned very well.

As much as I appreciate seeing the wider spectrum of Lawson’s work in the book, it is the concentrated interior portraits that I keep coming back to. Time and again, I’m discovering new details even as the details might make me question what I really respond to. These might be an assortment of remote controls that appear carelessly scattered next to a sitter; an ankle monitor worn by a young woman who is reclining in the nude on a set of stairs; a young girl hiding her face behind her father who is posing for the camera.

All of this points to the fact that much like all good photographs, Lawson’s demand to be seen as much as read: they are made with intent and dedication, and they demand the same from their viewers. This brings me back to why photography is such a semi-art. There is the fact that photographs emerge from the world that we encounter right in front of us. They make us believe that we look at a part of the world.

At the same time, these photographs are art. This means that they are really more about their maker, Deana Lawson, than about those who find themselves in the frames.

In the end, this means that regardless of what we make of the photographs, we also have to become aware of what we want them to do for us. We can pretend that this aspect is irrelevant. But why would we even look at art if we didn’t allow it to see ourselves reflected in it — possibly in ways that challenge what we like to think about ourselves?

Deana Lawson; photographs by Deana Lawson; edited by Peter Eleey & Eva Respini; essays by Eva Respini and Peter Eleey, Kimberly Juanita Brown, Tina M. Campt, Alexander Nemerov, Greg Tate, plus a conversation between the Deana Lawson and Deborah Willis; 144 pages; MACK; 2021

If you’ve enjoyed this article, you might enjoy my Patreon. Also, I maintain a Mailing List. You can sign up here. If you follow the link, you can also see the growing archive. Emails arrive roughly every two weeks or so.