A couple of years ago, I compiled statistics of the photobooks featured in Martin Parr and Gerry Badger’s The Photobook: A History, volumes 1 and 2. Volume 1 features 191 books by male artists and 18 by female artists. The ratio is very slightly less skewed in volume 2: it’s 174 vs 37. But note that I counted books and not artists: volume 2 features 11 books by Roni Horn, a fact that drastically lowers the already very low number of female artists. As you can probably imagine, the numbers of white people versus people of colour or of Western European/North American vs the rest of the world are equally depressing.

On 12 November 2021, the winners of the 2021 PhotoBook Awards were announced. What They Saw: Historical Photobooks by Women, 1843–1999 by Russet Lederman and Olga Yatskevich was chosen as the Photography Catalogue of the Year (full disclosure: I contributed an essay to the book). In very obvious ways, What They Saw serves as the much needed corrective to the very skewed field presented in books like The Photobook: A History (and similar publications).

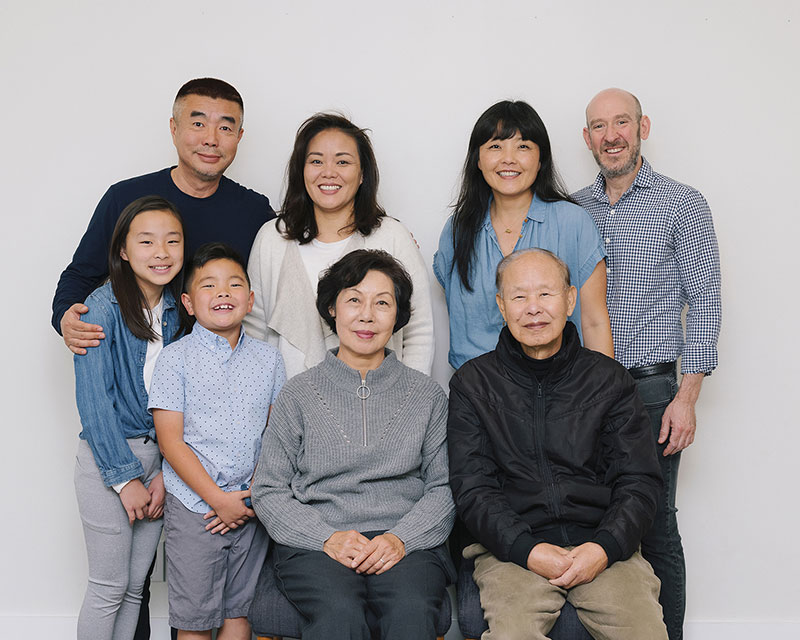

Lederman and Yatskevich are two of the driving forces behind 10×10 Photobooks, a non-profit with a focus on the photobook. I spoke with Lederman and Yatskevich after the release of What They Saw (before the announcement of the PhotoBook Awards). The following conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Jörg Colberg

Let’s start out with talking about 10×10 Photobooks. What’s the idea?

Russet Lederman

We’re almost 10 years old now. We started in 2012. We started as a resource for the community, a way that people interested in photobooks could meet up. Olga had created the Facebook group a few months before and organized a meet-up at a small Japanese cafe in Long Island City. She asked me and my husband, Jeff, to bring some of our Japanese books to share. In essence, that created the first salon, which became part of 10×10’s multi-platform programming.

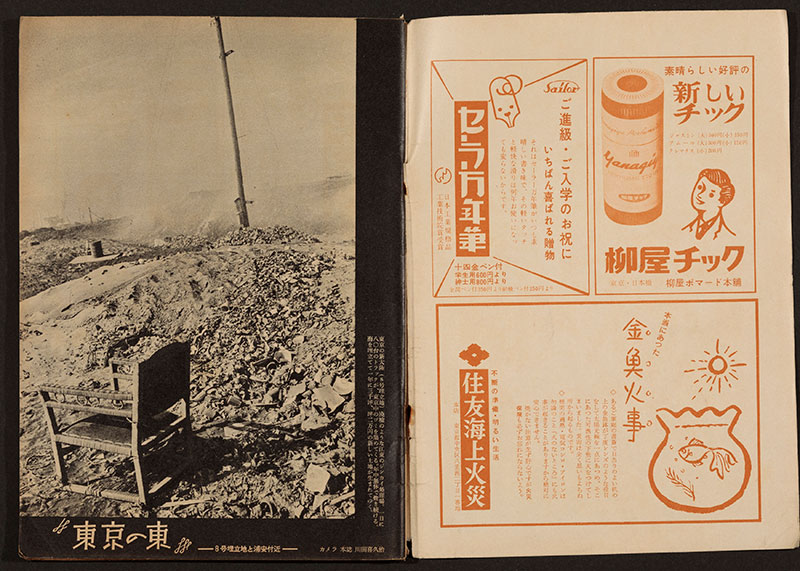

We then realized that more people would want to see these books. So we launched our first Reading Room, also in 2012, which was timed with the New York art book fair, in conjunction with ICP. It was a Japanese Reading Room of 100 books. We reached out to friends in Japan, and they sent books. It was a success, and we continued to offer reading rooms in 10×10’s programming.

Now we also have a grants program to further support research in photobook history specifically. This history is still very young, starting in 1999 with Horacio Fernández’s show and book Fotografía pública/Photography in Print 1919–1939 at the Reina Sofía. Many of the contributions since that anthology have been mostly from collectors and have been highly biased. Most of these collectors have been of a certain age, socio-economic, and racial background. This has skewed photobook history to be less inclusive.

We felt that broader voices for this history should be included. The research grants area way to do that. We give a topic each year. This was our first year, and our board members Dave Solo and Richard Grosbard spearheaded it. We chose the theme of women to sync with the current What They Saw project. But that is not necessarily what the grants will focus on in the future. They will be in underserved areas that need further research.

JC

For those who don’t know, the Reading Room — what is it? What do I have to imagine when I think of a Reading Room?

Olga Yatskevich

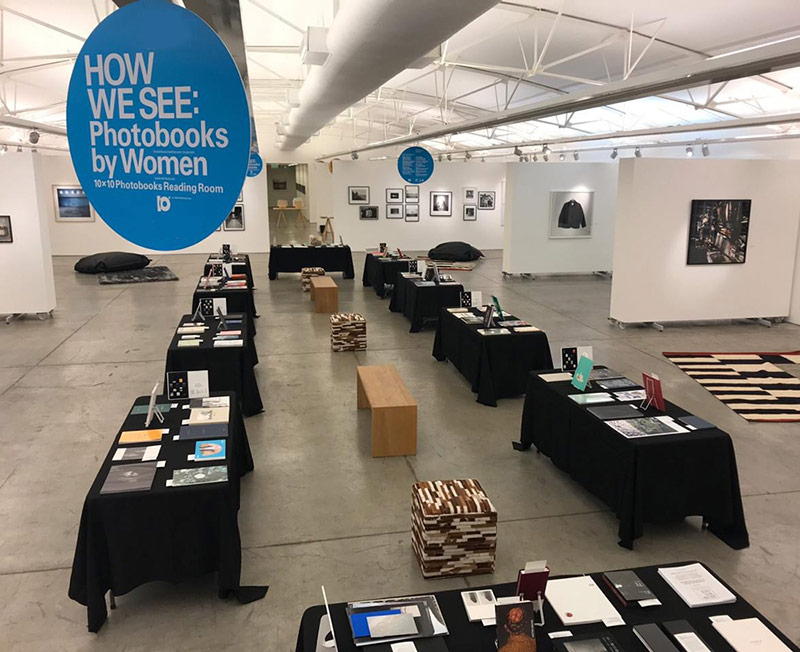

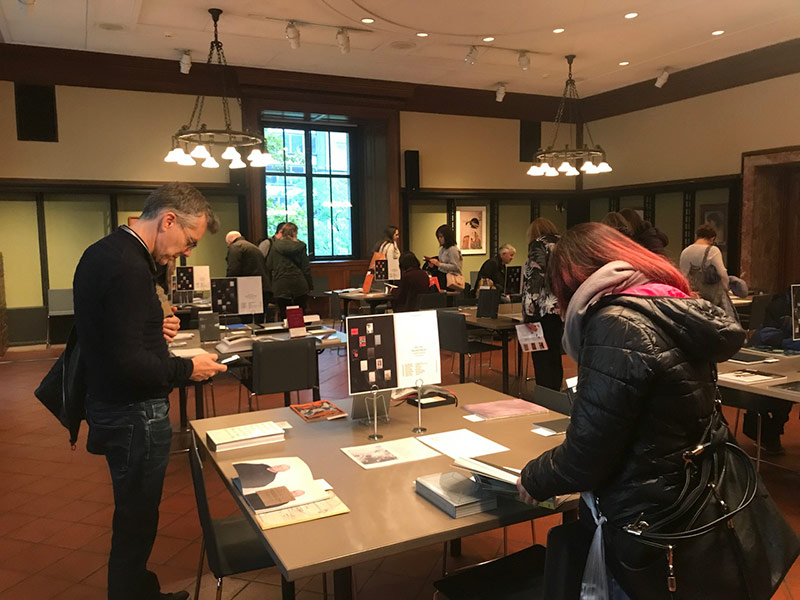

As Russet said, our first Reading Room was focused on Japanese photobooks. The idea was to bring contemporary Japanese photobooks that were not easily available in New York. We invited 10 people who selected 10 contemporary photobooks by Japanese photographers, and we then brought them into a space: a Reading Room. It was important for us that people had access to the books, could sit down, look through books, and really spend a good amount of time with them. We did have people who had spent a couple of hours taking notes and asking us where they could purchase those books.

That idea translated to all our other Reading Rooms where we invited people to come and spend time with the books and see them in the context of the entire project. The Reading Rooms will usually last over a weekend or a couple of days, and we usually take them to several locations. It’s important for us that after the project, the books are donated to a library where people can still access them. To record the projects, we started publishing our publications, the catalogs. So each Reading Room is also presented in a book format.

It was important for us that people had access to the books, could sit down, look through books, and really spend a good amount of time with them.

— Olga Yatskevich

JC

I was going to ask about that. There was also an American 10×10.

OY

Our first one was on Japanese photobooks. Then it was American photobooks. Then we focused on Latin American photobooks. After that, we moved to contemporary photobooks by women. The last one is historical photobooks by women.

RL

We should add that in between, there have been pop-up events that are similar to Reading Rooms. We did a hybrid reading room / book fair event called Awake with the Magnum Foundation, where we invited a bunch of independent publishers to each have a table. They did not have to pay for the table, so it was not like a commercial fair in that sense. Under the theme of protest, they could share their books. In the middle of the space, we also had a long table with donated books and books from the ICP Library on protest. Those not owned by ICP were donated to the Brooklyn Museum at the end of the project. Unlike many private collectors who might sell their collection to an institution, 10×10 always donates any books we receive for a project. Our goal is for the books to remain in an institution where they can be accessible to the public, such as the New York Public Library, the Brooklyn Museum Library or other public institutions. We’re trying to reach various types of photobook people, as well as introduce the concept of the photobook to a new and expanded audience.

JC

The previous project was How We See — Photobooks by Women. Now there is What They Saw — Historical Photobooks by Women. I’m curious about this leap from a (for a lack of a better word) curated survey towards what actually is real scholarship. How did that transition come about? Can you talk more about this project?

OY

I think with all our projects, we’re trying to figure out what works the best for each project. But also try not to repeat the same patterns. For our CLAP! publication, we expanded the number of people who selected books and asked them to select between 8 and 12 books. For our How We See project we asked experts to each select 10 photobooks by women. Through conversations and feedback from that Reading Room, we realized that there was a very strong interest in historical photobooks by women. We agreed that it was also time to rethink how we approach this project. This latest project, What They Saw, is arranged in chronological order.

RL

In How We See, we also had a historical selection, which was not in the Reading Room. It was more of a reference section where we asked librarians, historians, critics, and writers to each recommend 10 books. What They Saw grew from that selection and expanded.

We also found that people were asking about books that women did in the 1920s, or in the 19th century that our historical reference section touched upon lightly. To expand research on these books, we reached out to experts who, for example, might be specialists in African photobooks or photography experts or scholars in South Asian photography.

We also found that how we define a book now in the 21st century didn’t necessarily hold true for what we had to use as a definition in some of the earlier periods, particularly in areas that did not have access to offset or other forms of printing. We found that for some women, their socio-economic situation was such that they didn’t have the funding or resources personally. So we started to include scrapbooks and albums and unbound collected portfolios to address this issue. The singular way of defining a photobook as a bound book with hardcovers distributed through either a trade or independently was not necessarily what everyone called a book or could make. What They Saw is not only about researching a marginalized group, in this particular case women, but also about expanding the definition of what constitutes a photobook to account for the obstacles women had to overcome. I should add that we define women quite loosely—for example, there is a book by a crossdresser.

JC

What were your most exciting discoveries?

OY

I’m still fascinated by the albums by Arabella Chapman that Russet found. I think those are incredible. Also, Alice Seeley Harris’ The Camera and the Congo Crime was something that I found really outstanding. It was published in the early 20th century. It can be considered one of the earliest examples of a humanitarian photography campaign. One Time, One Place by Eudora Welty, a well-known American author, captures life in her home state of Mississippi in the mid-30s. It was published as a book four decades later. Also, Passion by Cameroonian photographer Angèle Etoundi Essamba, published in 1989, offers complex, empowering and beautiful portraits of Black women, breaking existing stereotypes. There are a lot of great discoveries!

RL

For me also the albums, of course. I expected that we would find most of the 19th-century and early 20th-century albums in the US, Britain, Western Europe because of the pervasiveness of photography and access by women of a certain class.

One of the exciting things for me was how women were able to make photography and the conditions and new definitions they created as a result. Take the Russian avant-garde artist Varvara Stepanova, who regularly worked with her husband Aleksander Rodchenko: you can’t find a book that is just her. And that’s true of many female members of the Russian avant-garde because most of the projects were collaborative. You have to remember that making a book is a multi-layered process. In the case of Varvara, she took Boris Ignatovich’s photographs and montaged them to create these beautiful endpapers of a repeated image of a Red Army soldier.

I also found the WSPU album (Women’s Social and Political Union), a Suffragette movement in the UK. A woman named Isabel Marian Seymour created that album from postcards made by Christina Broom and others. Christina Brooms is amazing. Her husband had a disability and was incapable of working. So she learned photography, started following the Suffragettes and photographed them. She also photographed British soldiers from World War 1, before they left for the frontlines. She set up kiosk stands to sell her postcards, which her daughter printed. Learning all of the things that these women had to do to survive and make money by means of photography is eye-opening.

Or take Alice Austen. She was one of the first LGBTQ+ figures in New York. She was a well-to-do Staten Island woman who, among other things, was a big bicycle advocate. These kinds of layers of pushing the envelope — not just in photography — were so interesting. She had long-term relationships with other women and circulated within a group of well-known lesbians. She went out with her camera and photographed New York street people, such as mailmen, newsboys and shoeshine boys. In my opinion, she’s the first street photographer. Her photos were in an unbound portfolio. Maybe we wouldn’t call that a book if we hadn’t changed our definition.

More contemporary: Adrian Piper did a book called Colored People. It’s a very conceptual, democratic project. She reached out to friends and colleagues and asked them to send her a photograph of themselves emoting based on tcliché emotional terms like “tickled pink” or “green with envy.” She then crudely colored portions of the received photos with the corresponding emotional color. She titled the book Colored People, which in itself is a racial commentary. We think of her as an artist and not often as a photographer or a bookmaker. These are the discoveries I really enjoy—ones where when we rethink assumptions and simplified classifications.

Learning all of the things that these women had to do to survive and make money by means of photography is eye-opening.

— Russet Lederman

JC

I think all of that might point to the fact that when we talk about photobooks, we keep them as photo objects. In a lot of anthologies, there is very little connection to the world outside or how the books actually connected with that time. What’s so interesting about your project is how it connects out into the world, in all these different circumstances. Is that something that you see in the same way? Maybe this can teach us something about how we can approach photobooks in a more fruitful manner?

RL

I think that’s very important. The photobook world is in danger of imploding. It’s a niche community and very insular.

In order for the photobook world to grow and survive, it has to speak to the larger society, and it has to speak to its time. This is why we asked each of the authors who wrote an essay for What They Saw to put the books within their time in a social, economic, political and cultural context. If you do not do that, you lose a lot of people who may need a broader context to appreciate a photobook.

Also, we wanted to avoid making the photobook something too precious. Instead, I see the photobook as something that should be part of our daily lives. It should be something that we enjoy in the same way we enjoy a paperback that’s sitting by the side of our bed. Maybe we turn the page down on it, and now it’s a bit dog-eared.

OY

Each chapter begins with an essay that provides a necessary political, social, and cultural background to place those books in their time period. They answer several questions, such as why these books were published and why they were possible. But they also pose questions: Why were there no photobooks published in certain periods? Or why were some subjects missing? It offers a more nuanced context to understand those photobooks.

RL

Olga came up with the concept of the timeline that runs throughout the book. It’s brilliant. It solves so many problems. There were several books, particularly in the 19th century, where we got a lead or someone mentioned something that could have produced a book. But we couldn’t find the book. The trail went dead. One example is an “assumed” journal with contributions by an Iranian princess, who had learned photography because she and her husband were members of the Shah’s court during the Qatar period, where photography was advocated. She kept her husband’s diary, which supposedly included several of her photographs. It’s a unique book that is most likely in a library in Iran, but we could not find any visual documentation of it. Still, we wanted to mention it, hoping that some future researcher would then say, I found it; here’s a photograph of it.

There were many things like that. The first Japanese woman to take a photograph collaborated with her husband. They ran a studio together in the Gunma Prefecture in the 1860s. All the work, for the most part, is attributed to him. There are two albums, which I found in an exhibition that was in a Hokkaido museum. Via my friend Yoko Sawada, we asked Kohtaro Iizawa, an expert in Japanese photography, if he thought the wife also contributed to these albums? He said, most likely, but that there was no definitive proof.

These were things that went into the timeline, along with events that could have produced atypical photo-literature that could have arisen from feminist or self-publishing. Magazines and the picture press were also a jumping board during WWII and after for womens’ involvement with photography. Some did phenomenal work in Life magazine or Vu, but they didn’t produce a book. Do we leave them out? This was a means to acknowledge that photography and words are not just a book. The picture press was a very inexpensive way — they were getting paid — for women like Lee Miller, who only produced one or two books. Quite honestly, I think the work she did for Vogue magazine during WWII is phenomenal. The timeline provided this really wonderful area to put things down that didn’t fit into a book-by-a-single-author definition..

We should mention that with What They Saw, we’re doing the Reading Room a bit differently. Typically, we travel a collection of books that 10×10 owns and then donates to an institution at the end of the tour. In this case, several books are unique albums that cannot be easily accessed. So we are partnering with institutions that already have deep holdings in many of the 258 books for the Reading Room. We also put together a fund to buy many books. That way, we can recontextualize what already exists within an institution’s collection and supplement it with the books we purchased.

We have two confirmed sites so far, the NYPL and the Hirsch Library at the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston. We will also be doing public programming, whether it’s public talks or posters in branch libraries or outdoor signage showcasing books by women photographers,, These public initiatives bring the books beyond the four walls of the reading room itself. This is a vital aspect: reaching out. In that sense, maybe educational is the best word. —empowering individuals to be their own experts.

The photobook world is in danger of imploding. It’s a niche community and very insular.

— Russet Lederman

JC

… and maybe get beyond this model of the precious object that is hidden away somewhere, that you don’t really have access to, and that’s too precious to engage with.

RL

That for us is key, wherever we are. In many cases, the books at the NYPL have library bindings, which makes them extremely handleable. People can touch them because they’re indestructible. You won’t see them in that Reading Room with fragile dust jackets on them. Instead, they can be touched to your heart’s content, while a few of the rare books will be in a dedicated space that will require registration. But those are the exceptions rather than the rule.