This site is closed for renovation. Programming should restart in early to mid November 2021, depending on how quickly an improved editorial mission and structure can be found.

Closed For Renovation

This site is closed for renovation. Programming should restart in early to mid November 2021, depending on how quickly an improved editorial mission and structure can be found.

I imagine that raising teenage boys is difficult — especially these days. Masculinity and its ubiquitous toxic outgrowths rightfully have become a focus point as all those affected by their many consequences have started to raise their voices. As a consequence, there has been a slow re-alignment of the roles and responsibilities of all members of society, with straight cis men being forced to re-evaluate their responsibilities.

I see the rise of neofascism all over the world as a direct consequence of both neoliberalism, with its direct appeal to sheer power and “might makes right”, and of that backlash against unfettered masculinity (whose two main pillars are misogyny and violence).

However ridiculous many of the leaders of neofascists parties look and act, their open support of a (partly imaginary) older order, in which “boys will be boys” and everybody steps back to their place in the back, has deep appeal to large swatches of people (in her new book, Natascha Strobl calls these parties “radicalized conservatives”, and she outlines the way they operate — I hope the book will find an English translation).

You can understand Great Britain’s Brexit slogan “take back control” as an open expression of a struggle over masculinity. England’s ruling class largely consists of a group of people who grew up leading very sheltered and privileged lives and who experienced masculinity mostly as a simulation of what all those other men do who don’t grow up being rich. It is the latter who feel wronged by a changed world, while the former have now found a way to finally experience some form of masculinity.

Whenever I see a picture of, let’s say, Nigel Farage attempting to convey the spirit of “take back control” I see a man who has no understanding of his own masculinity whatsoever and who panders to what he thinks it might mean. This is cartoonish and sad, but people don’t respond to visuals. Instead, they respond to a man airing their shared grievances.

It’s the same mechanism playing out when, say, Donald Trump climbs into the cabin of a truck and for some short moment acts out what he imagines the corresponding masculinity might be. The fact that these people would not drink beer or get into a truck when they’re not acting for the public is largely irrelevant because it misses the real point: however privileged they might be, neofascist politicians feel connected to the grievance they exploit. Resentment is a hell of a drug, especially when it plays out over masculinity.

I imagine that this situation creates a terrible conundrum for parents, especially fathers: how do you raise your teenage boys in such a way that they become decent people, possibly avoiding the shit that you’ve done in your own past, while larger parts of the outside world present the exact opposite of that as the go-to model, where, for example, thoughtfulness and care for others often is derided as “being woke”?

And then if you’re a teenage boy, how would you respond to all of that? I’m not a father, so I don’t have access to this type of perspective. But I was a teenage boy once, albeit one who did not fit into the standard masculine model. I didn’t play or watch sports (because I wasn’t interested), and the competitiveness that comes with standard masculinity struck me as a complete waste of my time and energy.

Had I grown up in the US, I have no doubt that I would have been relentlessly bullied by the “jocks”. But I lucked out and grew up in West Germany. It’s not that there’s no bullying in Germany. But it’s not part of the overall fabric of society in the way it is in the US where bullying essentially is part of the wider culture. When I first came to the US, I was shocked how by the open and completely uncritical depiction of bullying in popular culture, which, of course, is also connected to coarse, violent language being equally accepted (“let’s kick some ass!”).

I remember that being a teenage boy placed me in this strange spot between being a child — with its world of play and make-believe — and being an adult. In my own ways, I’d try to navigate the possibilities, even as I was aware — as teenage boys are — that it is the adult world that is to be emulated. The energy of child play got transferred into anything that was filled with adult possibilities, and inevitably that meant violence and power.

Teenage boys aren’t the greatest judges of their own (or other people’s) responsibilities, and for sure they have terrible impulse control — which, if you think of it, sounds pretty much like the behaviour of the various neofascist leaders that you can find all over the world (an exception might be provided by Poland’s Jarosław Kaczyński, who pulls the strings in the background).

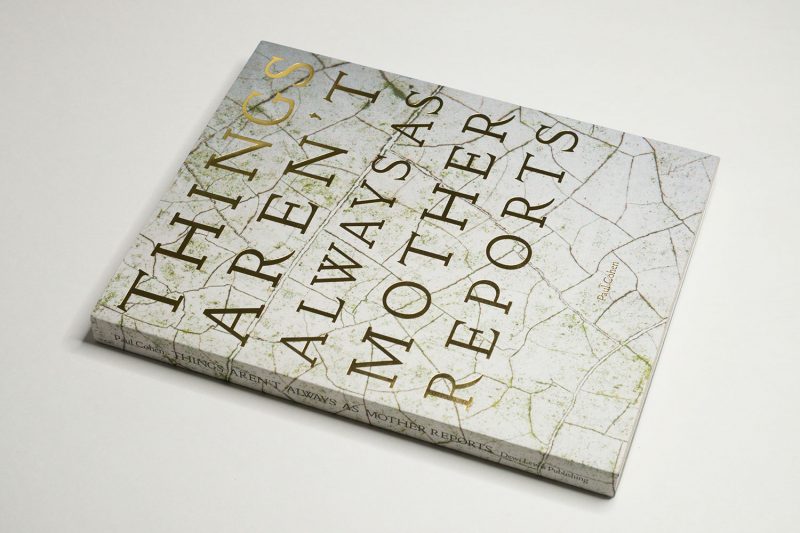

Paul Cohen depicts the conundrum he’s finding himself in as a father of teenage boys in Things Aren’t Always As Mother Reports (published by Dewi Lewis). If there is a photobook that feels incredibly relevant for that part of the world — England, it’s this one.

The book contains a lot of portraits of his sons, some tender, others filled with the kind of teenage violence that is always just a short step away from actual disaster. In addition, there’s the world these boys grow up in — London. From that environment Cohen extracts traces of things that might reflect his own struggle: trying to be a good father for his own children. There’s neglect in the lived environments, which manifests itself in a number of ways: crumbling buildings or infrastructure, but also traces of the people affected by it.

Consequences of violence are frequent: there’s a picture of a burned out house, a row of what look like police technicians looking to collected evidence of some violent crime (right next to them, a bouquet of flowers is propped up), a small graffito in support of a fascist party on an advertising poster, and more.

Even as the book ends on a hopeful note — one of the sons is shown against a bush of roses, his hands stretched out towards the sky with his eyes closed, it’s not clear whether things will end well. Cohen’s conundrum is shared by other parents: how do you raise your children in a world that is ruled by people filled with disdain for all things that help people be better people? I have no idea.

The book also conveys a sense of possibility. I’m reluctant to use the word “hope”, in part because it has become such a cliche in US journalism and writing that concerns itself with our times. Mind you, in principle hope is good — but it ought to be more than the equivalent of a sentiment on a Hallmark card.

Maybe this is a projection on my part (I know Paul Cohen quite well). But I sense that he knows that things are going to be alright for his boys, because as a father he has done the best job he can.

Recommended.

Things Aren’t Always As Mother Reports; photographs by Paul Cohen; essay by Val Williams; 104 pages; Dewi Lewis; 2021

Rating: Photography 4.0, Book Concept 3.0, Edit 3.0, Production 4.0 – Overall 3.6

A little while ago, there was a discussion on Twitter that centered on a photograph someone had taken of a young woman on the New York subway. The woman, a mother of two young children, was wearing a short dress, and she was clearly struggling to deal with her two very active children. According to his own testimony, the male photographer had sat across from the family and taken his picture on the sly. I’m not going to link to the picture in question or show it here. I am a member of the camp who thinks the photograph should not have been taken (for a number of reasons).

There obviously is a topic here that extends beyond this particular case in question. Last year, I wrote an article about consent that focused on what I see as photographers’ obligations. It might be worthwhile, though, to approach the subject matter from the other side: from the vantage point of those find themselves on the other side of the camera.

There was a discussion on Twitter about the photograph in question that resulted in a fairly predictable outcome: proponents of so-called street photography, but also others, pointed out that the First Amendment covered what they do. If, in other words, free speech is guaranteed then there is no way for anyone to prohibit the taking of a photograph (or the particular photograph in question). Second, it was pointed out that in the United States, courts have ruled that there is no expectation of privacy in a public space.

Both of these justifications are legal ones. However, when people speak of consent, they don’t think of that as only a legal entity. There also is an ethical component to it. Just because you have the legal right to do something does not mean that you actually should do it, in particular if it causes offense to other people.

I always feel that people bring up the First Amendment not to have an actual discussion but instead to shut it down. Who, after all, would want to be on the side of people who want to restrict free speech?

However, the legal argument is not as absolute as you might imagine. If you associate the taking of a photograph with the act of speech, then no photograph or no act of taking a photograph could become illegal. But that’s not the case. Possibly the most extreme example is provided by child pornography. According to the US Department of Justice, “Images of child pornography are not protected under First Amendment rights, and are illegal contraband under federal law.” I don’t think anyone would want to start an argument about this.

In a similar fashion, there are other types of photography that are expressly prohibited. For example, for very good reasons a growing number of states in the US (including New York State) and countries all over the world have made so-called upskirting illegal (here‘s a good article about it).

There is a second point concerning laws: courts only apply existing laws. If US laws state that people can have no expectation of privacy in public, that might not reflect how people actually feel about it today. It is possible that in the future legislation will be passed that defines people’s privacy more strictly. This is what happened in Europe, where the EU created the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR; in part as a consequence of what the EU perceived as excessive behaviour by the likes of Facebook).

In the GDPR, data include photography as well — which makes perfect sense, since the vast bulk of photography is digital. As you can imagine, this has created a lot of problems for photographers.

The question of consent might extend beyond the moment when a picture was taken, and it can become tricky as outlined in this article by Erin MacLeod: should you publish photographs of your ex-wife if she does not giver her permission? The obvious answer is: no, but as you can imagine — photoland being photoland — the pictures were published in a book.

But as Aileen Smith, who was married to W. Eugene Smith, has demonstrated, another world is possible. One of the most iconic photographs in the history of photography, a picture of a mother bathing her severely disabled child, has now been essentially withdrawn from further circulation: “Generally, the copyright of a photograph belongs to the person who took it,” Smith is quoted in this article, “but the model [subject] also has rights and I feel that it is important to respect other people’s rights and feelings.” (my emphasis)

In that Twitter discussion I mentioned above, there was a very interesting and telling aspect: last time I checked, every woman who commented on the picture saw it as problematic. All of them immediately sided with the young woman that had been photographed. There also were a lot of men who joined them. In contrast, the defenders of the picture and the practice that led to it were all male.

What I ended up wondering was the following: if you’re engaged in some practice that a growing number of people see as problematic — if, in other words, they don’t want to be photographed without their consent — how can you justify doing it anyway? As we saw above, you can invoke your legal rights. But that only covers your legal base. You’re still left with being on the wrong side of the ethical aspect of it all.

In particular, if you’re some guy with a camera, why would you photograph a young woman who is wearing a short dress and is struggling with her two young children without her knowing it, without her consenting to it? I just don’t get it. That just feels to wrong to me, regardless of the fact that it happened in a public space.

The fact that the space was public doesn’t make this all any less intrusive. The public space, after all, does not mean the same thing for men and women. Here’s the UN: “Sexual harassment and other forms of sexual violence in public spaces, both in urban and rural settings, are an everyday occurrence for women and girls in every country around the world. Women and girls experience and fear different forms of sexual violence in public spaces, from unwelcome sexual remarks and gestures, to rape and femicide. It happens on streets, in and around public transportation, schools, workplaces, public toilets, water and food distribution sites, and parks.”

For you, as a male photographer, it might just be a cool photograph. However, for your subject, the young woman in a short dress, it might just be another one of those small humiliations to live with. You might tell yourself “oh, she didn’t notice because she was busy with her two kids”. But how would you know? As far as I know, parents of toddlers are hyperaware of their surrounding because toddlers tend to be so unpredictable. And even if she didn’t notice — does that make it any better?

One of the common justifications for street photography is its own history. There are all those practitioners in the past who did it (the vast majority of them men). That might be the case. But I personally don’t see how this justifies engaging in it today without any consideration for what people think is acceptable behaviour. If people don’t want to be photographed without their consent, it’s an odd justifications to say “but people didn’t mind in the past,” isn’t it? Societies change over time. Certain things either go out of fashion or usually for very good reasons aren’t acceptable any longer. For example, many parents do not want their children to be photographed by strangers.

We also have to remember that we’re talking about photographs here, photographs done for the purpose of art. We’re not talking about journalism or anything that has a very different function and value. Typically, when I make my case that photographers ought to get consent, the whataboutism of photojournalism pops up (“but what about photojournalists?”). This sounds like a good point, but it actually isn’t.

Even though the world of journalism is different than the world of art, it has its set of parameters for which pictures it considers appropriate. There are certain types of pictures that you won’t find in newspaper or on news websites, typically out of consideration for the dignity of those portrayed and their next of kin (this might include victims of terror attacks, soldiers who died in war, etc.).

There have been frequent arguments over the validity of whether or not certain pictures should be shown in the news. What I find striking is that such arguments typically contain a lot more nuance and consideration for people’s feelings than when art photographers talk about street photographs. There, the first thing you hear is: First Amendment rights. Invoking one’s the First Amendment rights should be the very last point made — after people’s thoughts and feelings have been taken into careful consideration first.

Furthermore, if as an art photographer there’s a picture you can’t take — for whatever reason — that’s not the end of the world. It’s just a picture. If anything, you’re presented with a challenge. The challenge is not to figure out how to take it anyway. Instead, it’s how to take an equivalent that avoids the underlying problems.

What this all comes down to is the following: photographers (me included) like to go out into the world, to create pictures from what is being presented to them. Those pictures then not only reflect the world but create a dialogue with non-photographers: here is something that can help us come to an enriched understanding of what it means to be a human being.

There’s no way you can and will have this form of dialogue if you go out into the world and ignore how all those other people — your possible future viewers — feel about how you can treat them with your camera.

In the end, it might all come down to one basic thing: respect. Have respect for how other people feel. If as an artist you want to be treated with respect, then you will have to do the same with other people — including those that happen to be in front of your camera.

If you’ve enjoyed this article, you might enjoy my Patreon: in-depth essays about and videos of books that cover my own personal response as much as the books’ individual aspects.

Also, there is a Mailing List. You can sign up here. If you follow the link, you can also see the growing archive. Emails arrive roughly every two weeks or so.

Forty years later, I cannot be certain that the restaurant my family went to most often on our yearly summer vacation in the German Harz region was called “Zur Linde.” The internet tells me that there existed such a restaurant a mile or two outside the small town we stayed in for two weeks. It now is closed. Further research yields the image of an old postcard that depicts the establishment. I’d like to confirm that the building looks familiar to me, but I am unable to.

If there’s one thing I remember about the restaurant, it’s that they would always served a Vorsuppe, typically a thin chicken or vegetable stock that was a bit on the salty side and had small assortments of tiny pasta and bits and pieces of root vegetables added. At home, there was no such thing as a Vorsuppe. Who would eat soup before their main dish? And what soup would be this insubstantial? This was very odd to me.

The fact that there was a restaurant with the name “Zur Linde” in approximately the location that I remembered means that I cannot have imagined this completely. The restaurant cannot merely be a figment of my imagination, given the likelihood of me remembering something fictitious that then happens to have an exact equivalent in the real world.

As Michael P. Romstöck‘s Zur Linde tells me, though, there is nothing particularly outlandish about a restaurant named “Zur Linde”, given that such establishments exist all over Germany. A Linde is a tree, which in English is called linden or lime tree (if this Wikipedia page is to be believed, and why wouldn’t it? Who would create fake information about trees on Wikipedia?).

As it turns out, linden trees are not only very common in Germany, they also appear to be as revered as oak trees. I had always thought of the oak tree as the tree Germans see as “their” tree. In West Germany, the 50 Pfennig coin featured a young woman planting an oak sapling (find the story/ideology behind it here). “In 1936,” an NPR story says, “the German Olympic Committee gave athletes an oak sapling for each gold medal they won.” Apparently, these trees were planted in a number of countries.

Regardless, Romstöck traveled across Germany to document linden trees and references to them. That restaurant I went to as a child would have been one (alas, it’s not included in the book). But there are others. There also are streets named after linden, whether in the form of a Lindenstraße (which coincidentally is the title of one of Germany’s most well known daytime soap operas) or as Berlin’s Unter den Linden boulevard that originates at Brandenburger Tor.

Of course, there are plenty of actual linden trees, some of them very, very old. A number is already gone. Yet they have been memorialized, given the function they served — a function that could have been ideological or practical.

There’s an appendix in the book that lists details of what is on view in the main section of the book (unfortunately, the text is only in German). The texts are pulled from a large number of sources. They cover a wide variety of aspects of linden trees, ranging from description of trees that are said to be 1,000 years old to an outline of an apartment for sale in Haus Linde, which is part of some retirement home.

Zur Linde is a very handsome production that is filled with a lot of very good photographs. But there is one problem: with the exception of the very first and last photographs, the pictures are always paired, which makes the book unnecessarily tight. The metaphor I’ve adopted to describe this phenomenon is stereotypical German techno: the incessant boom boom boom boom boom boom allows none of the photographs to unfold their beauty. There is no space for a viewer to take something in. These photographs need breathing space.

In particular, some of the photographs are simply superfluous. Do I need to see some detail photograph of something that right next to (or before) it was already shown? I don’t think I do. Instead, as a viewer, I want to feel that I can spend some time with what I’m presented with, having the chance to discover things on my own — instead of being hit over the head with either some detail or the next thing.

After all, Romstöck not only has a keen eye, but he also discovered a number of incredible trees. For example, a number of them have all kinds of often elaborate contraptions built around them, part of which look like providing support, part of which appear to allow for access (in the form of platforms). And there is something uniquely German about the photographs, even if that Germanness is a lot more complex than non-Germans might expect.

I’m obviously no disinterested observer, given that I’m not only German myself, but I’ve made Germany the topic of my own photography. I don’t know how someone with a different background will react to the work. But I’m thinking this book will be of interest for those who want to have a peek at Germany, seen through German eyes that are able to perceive an aspect that’s so obvious that it’s easy to overlook.

After all, photography can be incredibly revealing when it focuses on that which is just too visible to warrant a photographer’s attention. There’s nothing exotic about Germany’s linden trees and all their various associations. But it’s exactly that which makes the book so interesting.

Zur Linde; photographs by Michael P. Romstöck; texts by various authors (German language only); 144 pages; Verlag Kettler; 2021

If you’ve enjoyed this article, you might enjoy my Patreon: in-depth essays about and videos of books that cover my own personal response as much as the books’ individual aspects.

Also, there is a Mailing List. You can sign up here. If you follow the link, you can also see the growing archive. Emails arrive roughly every two weeks or so.