In the first part of my conversation with Karolina Gembara, we spoke about the massive protests in Poland that erupted when a constitutional tribunal outlawed all forms of abortion and about her part in a photographer-led collective that documents these protests. In the following, other aspects of her work are going to be talked about, including (but not limited to) the agency of photographs and migration in photography.

Jörg Colberg: You mentioned your research already. You talked about the agency of images. What have you learned by observing and being part of these protests? What have you leaned from seeing the images being distributed?

Karolina Gembara: I recently wrote a short text, where I’m trying to approach a question that I’ve been asked a lot: “do images, do pictures change the world?” I must say it’s an annoying question that requires deconstruction. When we approach this question in a very narrow sense — when we understand “photography” as a singular image, as just a picture in a newspaper or on the internet or as an object, if “the world” means literally global politics, if “change” means only improvement (because that’s how we tend to think about these things) — then it’s easy to doubt any agency.

The question should be: what is the character of agency? If you apply different culture turns like performative, pictorial, objects, or ethical turn… If you build this broad, methodological perspective, then you can really see things and especially art objects having impact or asking you to do something. It could be as nuanced as getting upset or angry, sharing, looking closer, or maybe even holding it. All of these events are agency.

When speaking about its character I mean to say that there’s a huge spectrum between oppression and emancipation. For example, oppression is when the police are taking pictures of us at a protest. They’re using the exact same tools that we do and they do it for a particular reason – to interrogate us. But when as part of the Archive of Public Protest (APP) we make a newspaper, we want people to feel equipped with the images and slogans and take to the streets and shout. We want to emancipate them. There’s so much happening in between these two positions.

For example, when the little boy Alan Kurdi died in 2015 and they found his body on the shore in Turkey a picture of him went viral. It was on every cover. The Independent said that if this image is not going to change the way we think about the refugee crisis, then nothing will. There was a lot of research about what this image has done. It has done a lot.

But in the context of the question “how does the image change the world?” it would be easiest to say it did not save the refugees. Thirteen and a half thousand people died since 2015 in the Mediterranean Sea. We didn’t stop the so-called refugee crisis. People are drowning. But there are several things that did happen.

Back then, David Cameron said in response to the event that they should take in more people. Of course, you can ask why not more than he proposed. But for some people, the world has changed because they entered the UK. Scandinavian NGOs that work with refugees got massive donations back then that also probably changed the situation for many people.

On the other hand, like I said not much has changed for the refugees who are still traveling across the Mediterranean Sea. There was another image a few years later, that was very, very similar, a picture of a Rohingya refugee. It was another three or four year old boy in a very similar situation. It did not end up on newspaper covers. Last year, in September, there was an image taken by somebody in Tunisia, exactly the same situation.

So you could say that the strong images are strong because they bring something that we are not very familiar with. Somehow, they shock us. But after some time, they become weak. All of these cases are worth discussing. I would say, maybe it sounds banal but there’s always something that does happen because of an image. And there’s a lot that does not happen — sustaining the status quo is some sort of activity too.

This discussion reflects the expectations and the needs we have towards images. In my opinion, there is no doubt that we can do things with images, and they do things to us — both when they are ephemeral through sharing on the internet and as real objects. The APP newspaper is a result of such thinking.

But one of the greatest examples for me is what happened with an image taken by Activestills, the Israeli-Palestinian photo collective. Oren Ziv took a portrait of a Palestinian activist who later got shot at a protest. That picture became a poster. And that poster became a shield. They put the the images on shields when Israeli soldiers were shooting. The image was protecting them.

So there’s this whole range of things that you can notice that images do with our help. I research visual culture. But at the end of the day I would rather ask how we, as human beings, change the world?

JC: Maybe this is a good opportunity to talk about a project you did with migrants coming to Warsaw. Can you talk about this a little? I think it’s called New Varsavians?

KG: Nowi Warszawiacy Nowe Warszawianki. It started as an idea to run a workshop. This is an old idea and not my invention. It’s a participatory project with some elements of photo voice, where you approach a certain group of people, and you want to do research with them. So I thought that I would create a group of people and I’d teach them photography. Financial support was provided by the city of Warsaw, which is still relatively liberal.

As a group, we would meet regularly. We would also go to galleries. I invited people to come and teach certain topics that I’m good at but also so they would meet other professionals and talk to them. I had a very diverse group of people, diverse also when it came to their ages. Initially I didn’t want to work with kids. But it turned out that I had four people under age 18 in my group. They were from different countries, with a different levels of Polish. Through the funding, I managed to buy them cameras.

The idea was really, really simple. I wanted them to speak about themselves and reveal as much as they wanted to. We never really talked about their traumas or their stories. Some of them had just arrived in Warsaw, some of them had been there already for a couple of years. Some were integrated, some still lived in the refugee center just outside the city. They simply built their stories.

We had an Instagram account, I posted some of the images they made. At some point, we had an open studio for portraits where they were the photographers. It came from an idea that it’s very easy for photographers like me to go and photograph refugees, to enter a refugee center or look for a protagonist and portray them. You take a picture and add some story or something. You represent that person. I wanted to reverse the situation where they are the authors, the creators.

At the end, we made a newspaper together. I edited some of the photos. I proposed the selection to them. I also had a journalist working with me. She was briefed about everybody and their photos, and then she would meet everyone and and based on the meeting write a little story.

We also had an exhibition, which funnily enough was the longest exhibition last year in our gallery because of the lockdown. We had a pretty great turnout and media coverage. I decided to use that with a very specific reason in mind. The day after the the opening, we launched an online petition because one of our participants, 17 years old at the time, and her mother faced the risk of deportation at any moment. We couldn’t let that happen. Thousands of people signed the petition. The media kept this story alive for weeks. That was a situation that we created, and of course, this is beyond the typical artistic activity here. But I thought that if this project was good for something, it was good for something like this.

Recently I completed another project where photography is only a pretext. During the Nowi warszawiacy workshop one girl mentioned her family struggles with finding a flat — landlords reject them because they are refugees. So I dedicated my time to become an agent to find housing. Alija was my partner in this project. We made a list and started calling people. The conversations were difficult for me, so I cannot imagine how difficult they were for a teenager.

In refugee families, children learn the local language much quicker than parents, so they start acting as adults — when going to a doctor, a layer etc. For her, I wanted to avoid that. The whole process was recorded on video, with images and audio. I also invited experts who explained what is housing discrimination is and why we should help migrants find homes.

The visual part is just a documentation. The most important part is that the family found a flat. The visual layer is present, but the core of this project isn’t visible in a traditional way.

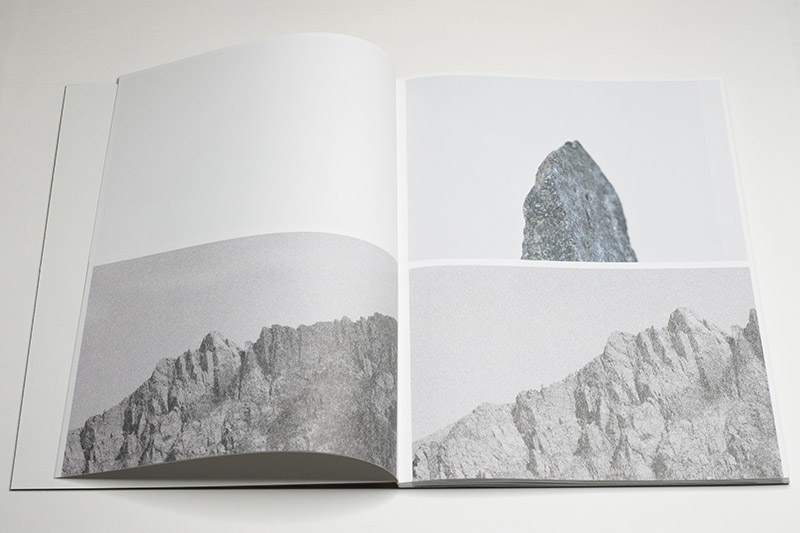

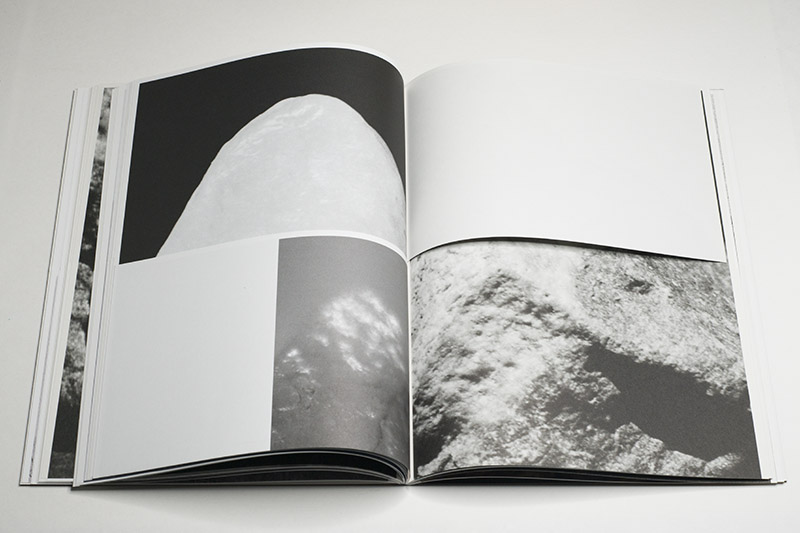

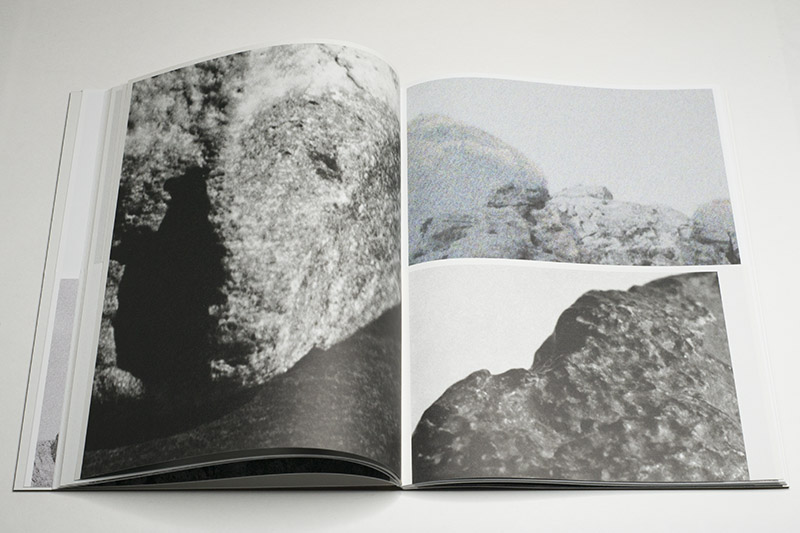

JC: Besides doing all these things, you’re also taking pictures yourself. There’s this project of the recovered territories, which I actually see as related to everything else. Your family came to Poland from what is now Ukraine, and they settled in an area that used to be German and then became Polish. So there is a refugee/migrant aspect to the whole work. Can you talk about this a little bit?

KG: Yes, all these things are connected. I think the first reason for the project came up when I was still in India back then in 2015. I had a phase of missing Poland, going through my family archive and making the resolution that when I come back, I’m going to explore something in my territory. Already then I must have known that I was not going to stay in India forever.

To be honest, I have to say that I do not like those sentimental, personal stories. I really wanted to avoid that and make this project as universal as possible. I spent a long time taking photographs, but also reading about history. I realized that I’m not talking only about my family here, because the journey from the east to west after the Second World War happened to millions of people.

Contrary to what Communist propaganda was saying for decades, this was a forced migration. People arrived from areas in what is today Belarus or Ukraine, and they were brought to houses that were still inhabited by German families. Those families were waiting for their turn to go to Germany because the borders of Germany also changed. So this happened not only to Poles but also to so many other nationalities.

I found out that my young great grandma and great grandfather moved in with a German family, and they lived together for a year. Happily. At first I couldn’t believe this story. At school, I had been taught something else. Back then, at the beginning of the 1990s history was still very black and white. Germans were always enemies. They were all Nazis.

So this was a revelation: “We lived here together until they had to go, and we were very sad. Then they would come every year in the summer to visit us. And we were writing each other letters.” I started exploring these unexpected parts of the story. It was easier to understand the sentiment for what had been left behind in Ukraine. But missing the Germans? This story goes all the way across nations. Obviously, the activity of the German compatriots… how do you call them in German…

JC: Vertriebene.

KG: That is a problematic aspect. But I do understand the tragedy of people who had to leave things behind.

JC: That’s the part that I knew before I learned about yours. They were always really right wing, and they had a big political influence in West Germany. I didn’t know the story until much later. And even if you read up on it now, the stories that you read are still about people in East Prussia who had to flee the Russian army. The story that you’re telling, I had actually never heard anything about.

KG: In all of these places, in all of those houses there were dramas happening. There’s a book by Magda Grzebałkowska called 1945. War and Peace. Month by month, she describes twelves stories. She says that while working on the book she discovered that 1945 was not the year of the liberation when everybody was happily going back home or taking over new places, new territories, starting new life. It was a year of death, desperation, migration, losing family, acquiring new furniture… It was crazy.

Many of those stories are about people who were from Prussia, who were chased away by the Red Army and had to cross the frozen sea with horse carriages. The ice would break and whole families would drown. It’s an amazing book. There were things in it that I read, and I remembered them from home: “this is not ours really” or “going back would be nice” or “what we left behind was so great”. That’s the historical part, that’s the sentimental part.

This project is not finished, yet, so I don’t know if I’m succeeding. But I’m trying to connect it with what we think of migration today. I’m trying to base my reflections on epigenetics, on how we pass on certain traumas, and how they are reflected in later generations. I see that in myself, whatever my grandma went through, her need to pack things, to be ready because “you never know”. I saw that behaviour in me when I was a child already.

I’m trying to connect all of that with migration today in the sense that I’m asking: are we able to realise that we have that migration experience in us? Again, I’m not talking about myself or people who live in the recovered territories. But almost all of us are children or grandchildren of migrants. Remembering that, even if it’s just something that we would have to wake up in our body, in our muscles — is there a chance that we are able to empathise with people who are in that situation today? I see this as a thread that is connecting the “1945”, but it’s going through generations, and it’s still in us. We should be able to realise that people who are migrating right now, who are forced to escape, are in the same situation we were in yesterday.

Maybe it’s a pathetic call for solidarity, to remember that this has happened already… I have many chapters in this project. There are images of German furniture present in our houses — what does that mean? How did we acquire them? What do we feel about them? Why are we even attached to them?

There’s a chapter about going back to Ukraine. Actually, last year, I was supposed to go to the village that my grandparents came from. Due to the pandemic I wasn’t able to go. So I made this little film, arriving through Google Earth in this village, and I’m looking around, looking for maybe the houses we see in photographs from many years ago. But it’s impossible to find them. There’s a cemetery but I cannot enter because of the limits of the technology. I’m basically so lost, and I don’t feel anything. This goes against that sentiment that was imprinted in me that there’s this paradise that we left behind. No, I don’t feel so. I feel really great in this post-German architecture in Breslau, in Berlin. Whenever I arrive in Krakow, I feel it’s abroad.

There are all these things that I adopted culturally without even knowing because we never really approached that experience. We didn’t work on it. We never really looked back at our history. We’ve been very focused on being a victim of the war, of all the oppression, and I think that’s the reason why the right wing is so strong right now.