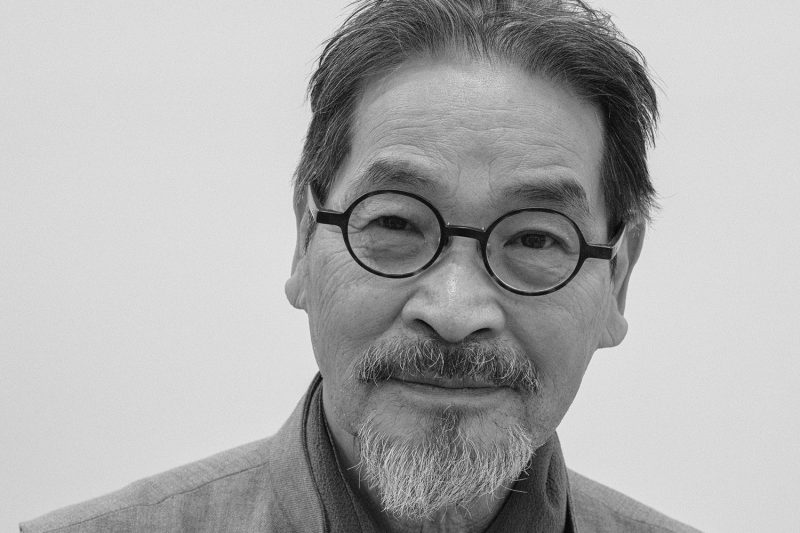

Having dreamt of waterfalls, Tadanori Yokoo decided he would have to paint some. Given there were no actual waterfalls nearby, he started looking at postcards collected over the years. But he had too few of them, so he started asking people to find postcards of waterfalls for him, not realising that the request would turn into a veritable deluge that was as difficult to stop as an actual waterfall. In the end, he turned the 13,000 postcards into Waterfall Rapture (Postcards of Falling Water), which was published in 1996.

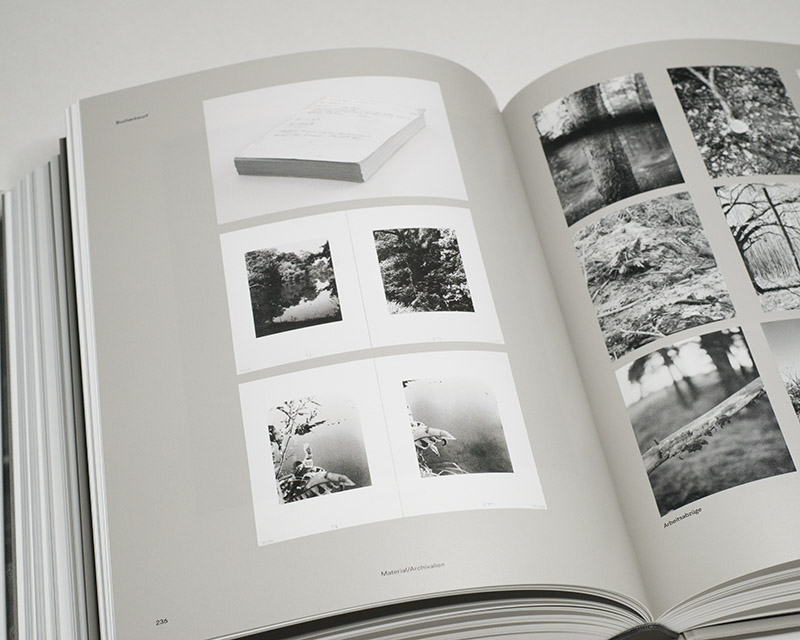

The book is mesmerizing for a number of reasons. To begin with, the postcards are organised by type, content, and/or era. For example, there are spreads that show postcards with lenticular images, spreads that show postcards of waterfall in the fall (red foliage), etc. (Someone must have taken the time to do that work.)

Furthermore, certain tropes repeat, but the number of actual tropes is surprisingly large. (Would this also hold true for sunsets?) Not surprisingly, some waterfalls feature more prominently than others. But their depictions might vary in terms of the tropes used, or the very same photograph might look very differently based on when it was hand-coloured (or possibly by whom).

In the end, the many postcards of waterfalls tell us a lot more than we might imagine. They’re only superficially postcards of waterfalls, but mostly expressions of our human engagement with them, with our wanting to share the joy (or maybe obligation) of being in the presence of a waterfall.

In Japan’s Shinto religion, kami — which you can think of as gods or spirits — play an important role. I’m simplifying this terribly, but much like people, kami need to be housed somewhere, which leads to the concept of shintai, “physical objects worshiped at or near Shinto shrines because a kami is believed to reside in them.” These could be a variety of objects, including mountains, which “were among the first, and are still among the most important, shintai, and are worshiped at several famous shrines”. Mount Fuji, Japan’s highest mountain (and an active vulcano), is the most prominent one (for a lot more details about Mount Fuji, see this article).

As a brief aside, Shintoism sees the kami of mountains as goddesses. However, in the past, this fact led to women being barred from mountains (or tunnels). Kittredge Cherry explains in Womansword — What Japanese Words Say About Women that this was because “the female mountain spirit enjoys the attentions of men so much that she would get jealous if a woman were around to distract the guys.” (p. 27) Amazing how even when believing in goddesses the sexism in Japanese society was still able to restrict women’s rights.

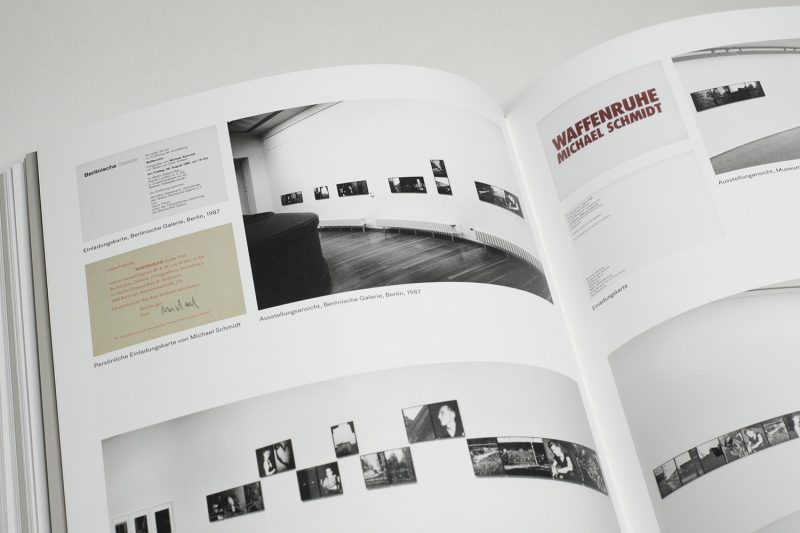

When I first encountered Fiona Tan‘s Goraiko, these aforementioned ideas came straight up for me. The book is a catalog published at the occasion of an exhibition at Sprengel Museum Hannover in 2019 after the artist had been awarded the SPECTRUM International Prize for Photography of the Stiftung Niedersachsen. The exhibition’s main piece was Ascent, a 77 minute long projection of images, sounds, and voices (there also exists a movie — I have seen neither).

After a series of install shots from the exhibition, the bulk of the book consists of a section entitled A selection from the archives. Essentially following Yokoo’s approch, Tan had first collected her own photographs and postcards before asking the general public (through an appeal facilitated by the Izu Photo Museum, which is located near the mountain). She then compiled the images into Ascent, with sound and spoken text added.

The archives section follows Yokoo’s approach from Waterfall Rapture. Specifically, every spread contains four images that each show Mount Fuji in a very similar fashion: the snowy peak, clouds around the mountain, cherry blossoms, trains running in the foreground, World War 2 era war planes above the mountain, crappy pictures taken from a rapidly moving vehicle, people posing against the mountain’s background… The list goes on and on.

In light of what I wrote about Waterfall Rapture, it might not surprise the reader to learn that the more of these types of tropes show up, the more interesting things get. It is akin to looking at a contemporary version of Katsushika Hokusai‘s Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji (the inevitable art-historical reference). But where the ukiyo-e artist’s concern was purely pictorially dealing with Japan, Tan’s is photo-sociological, diving into the uses of the nation’s most famous symbol.

Another brief aside: Mount Fuji might be the only specific “object” that is represented by two emojis: directly as the mountain itself — 🗻 , and indirectly through Hokusai’s famous wave, most closely followed by the Apple version of the wave emoji — 🌊. Of course, Hokusai’s wave only exist because it crests on top of the mountain in the image’s projected view.

As becomes obvious from Goraiko, the real value, the real meaning of photography can only be found beyond its photographs. These are just stepping stones through which we communicate with one another.

This fact becomes especially clear in the case of Mount Fuji, given that its prominence in the landscape and the nature of that landscape itself allow for a variety of uses that simply do not exist for most other landmarks.

Seen that way, it is not surprising that Hokusai would produce his Views at a time when photography almost existed (remember, around the time photographs were already made, but all efforts focused on fixing them, to prevent them from fading away). There’s something proto-photographic about ukiyo-e, in the sense that it tapped into the same sensibilities that photography would most successfully exploit.

Already a Shinto icon, Mount Fuji thus became a cultural icon, whose relevance quickly became known outside of Japan as well. Flying into Tokyo twice, I did crane my neck to see it out of the airplane’s window. It really is spectacularly beautiful, given its striking symmetry that is almost perfect. But Mount Fuji also is something that I knew and felt had the larger relevance I had heard of and I was now able to connect. I didn’t take any pictures, though.

Goraiko; images by Fiona Tan; texts by Lavinia Francke, Stefan Gronert, Fiona Tan; 176 pages; Van Zoetendaal Publishers; 2019

I’ve set up a tip jar. If you’ve enjoyed this article (or site), feel free to leave a tip to support my work. Thank you!

Also, there is a Mailing List. You can sign up here. If you follow the link, you can also see the growing archive. Emails arrive roughly every two weeks or so.