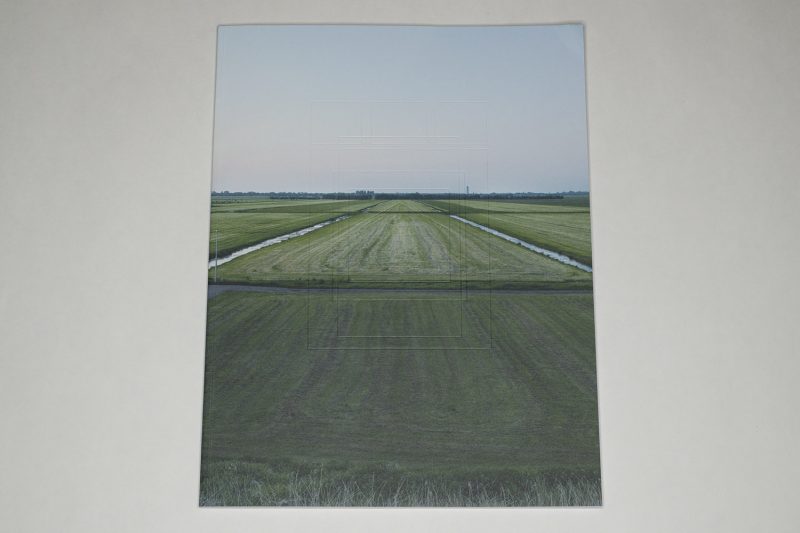

I became aware of Elspeth Diederix‘s When Red Disappears the way I learn about 99% of all photobooks — online, possibly through some marketing email. I don’t remember where and when, but I do remember that I made the choice not to pursue the book (I will contact a publisher and ask for a review copy when I see something that I feel I want to cover). After all these years, I have a pretty good idea what a book might look like when seeing it presented online.

But there still always is everything the book, the object, brings that cannot possibly conveyed by digital photographs plus the obligatory advertizing copy. So making such decisions online isn’t fool proof. In the case of this particular book, I found out when the publisher in question, Hans Gremmen’s FW:Books, sent it to me (along with others). I would have easily agreed to reviewing the book, had I come across it as an object and not online.

I feel this lesson is something that anyone interested in photobooks will have to keep in mind, especially when operating on a limited budget, which requires some careful decision making: the internet is great to share information about books, but it actually is pretty lousy when it comes to conveying their physical attributes.

A brief digression: Another major shortcoming of the internet is its tendency to amplify the voices of those who don’t really need such amplification, while others (more often than not women or minorities) simply aren’t heard or are only heard by a very small number of people. A lot of photobooks by famous photographers sell very well not because they’re any good but because they get massive play, and no critic is willing to write anything negative about them — while, in private, admitting openly that, well, they’re terrible.

My digression doesn’t have anything to do with When Red Disappears… Oh, whom am I trying to kid here? Of course, this article is going to get read and shared a lot less widely because the photographer isn’t a household name in large parts of photoland.

The reality is, though, that this particular book is more nicely produced than roughly 80% to 90% of all photobooks, and for that reason alone it deserves to be appreciated. This might sound like an incredibly silly thing to say, an endeavour of engaging in photobook-production geekery. But it is not, because without the production and the choices made for the underlying body of work, the book would be one of the many forgettable ones produced every year.

In other words, what actually can — and I would argue should — be gained by very carefully considering the form and materials of a photobook is demonstrated very clearly here. For those who have followed Gremmen’s work as a publisher, this will come as no surprise.

The book features a body of work produced under water, details of some Dutch ocean floor, with the various organisms living there being the subjects in what comes across as a fairly murky world. As the essay at the end of the books makes clear, there are various reasons for things looking the way they do under water, including a limited amount of actual light, the colours provided by the organisms themselves, and the way optics plays out in the sea.

“The first colour that vanishes is red,” Diederix is quoted in the piece, “by about 30m down, the yellows have been lost too”. Even though I studied optics as part of my undergrad degree in physics, this had never occurred to me. I must have seen many films and pictures taken underwater, and I had never asked myself why things looked the way they did.

Diederix’s achievement is to have taken photographs that are amazing despite the fact that they don’t look anything like the kinds of imagery one might know from some touristy location, with colourful coral reefs shining brightly in some impossibly blue water. Here, things are very reduced. Where it is visible the ocean floor looks like some uninviting grey desert, and marine life doesn’t look too interesting, either. Photography is good when it can make the remarkable look remarkable. But it is great when it can do the same for the unremarkable, the kinds of places photographed here.

Having the pictures is one thing, making a good photobook out of them is another. Hans Gremmen knows how to do such a thing. In a variety of ways, When Red Disappears invites comparisons to Awoiska van der Molen’s Sequester. In both cases, the printing of the book needs to deliver so that the book will come close to the photographic prints by these two Dutch artists. And it does.

Much like Sequester, When Red Disappears appears to have been printed on black paper, so the added inks literally lift the images out of the darkness. What looks like black paper, though, is not that: the printer worked with white paper and fifteen times as much black ink as usual. In addition, the edges were treated to be black (Hans Gremmen kindly revealed these production details). The overall effect is tremendously beautiful — and it is exactly this that simply cannot be appreciated in digital reproductions (I might also add that the smell of those inks is quite something, but that is really only production geekery).

As far as I’m concerned, a photobook ideally is more than a container for photographs, whether we’re looking at catalogues or monographs. All too often, it is not. And often enough, that’s OK. But I feel the photobook itself should be its own object of art — possibly even at the expense of the photographs it contains. If I had to make my case in front of some jury, When Red Disappears would be an ideal example.

Honestly, if you can’t appreciate this book regardless of whether you like the pictures or not, then I don’t think you understand the form of the photobook and the many aspects that go into its production (printing, material choices, etc.). But there’s more to the form: it will also make you like the pictures or, at the very least, make you appreciate them. So here we have photographs from the murky waters of the Dutch sea, presented in all their glory. This is photobook making at its very best.

Highly recommended.

When Red Disappears; photographs by Elspeth Diederix; text by Philip Ball; 88 pages; FW:Books; 2019

Rating: Photography 4, Book Concept 5, Edit 4, Production 5 – Overall 4.5