Paraphrasing John Szarkowski, Gerry Johansson‘s Germany is not the Germany as I know it. Unlike the late MoMA curator who disdained Richard Avedon’s photographs from the American West, I do mean my comment in the best possible way. After all, isn’t it an artist’s role to offer us new insight instead of merely confirming what we already know?

Now approaching the end of my second decade living in the US (a scary thought!), each visit to my former home land brings with it a mix of recognition, familiarity, strangeness, and unease. Much has changed in Germany since I left (my most recent stay in Germany brought me to a country where there are now neo-nazis in parliament and one of the dominant parties of my childhood is imploding because it sold out its clientele), while everything has essentially remained the same. At most I felt that maybe the volume had been turned up, albeit just a notch. Compared with the atmosphere in the US where the level of anger and frustration has become unhealthy, Germany felt like a haven of peace and quiet — a place that, in fact, would actually benefit from maybe a little bit more conflict and less general agreement about everything.

I suppose it would take a foreigner to grasp the essence of this strange country. Johansson might be the best choice for the job, someone who quietly treks across vast parts of the land, to take it all in, and to immortalize each location, however small, with a picture. Thinking again about what I wrote above, namely that the result is not the Germany as I know it — maybe that’s the wrong way to say what I wanted to express. I know the Germany in Johansson’s pictures quite well, but it’s not the Germany that comes to my mind when the topic comes up.

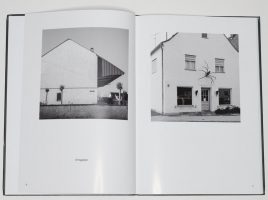

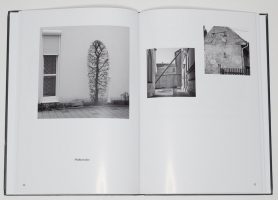

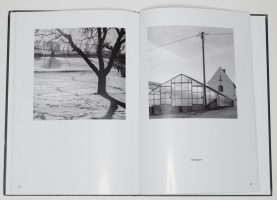

What this particular photographer does with his square-format camera seemingly amounts to a series of formal exercises, fitting a usually nondescript scene into the frame in such a way that the result is visually pleasing. While this description is true, the outcome is a lot more interesting than one might imagine. Johansson is a formalist (please note that I don’t mean this in any kind of negative sense), but the results never end there. With the photographs’ formal qualities resolved, the viewer’s enjoyment derives from more than seeing just that: the photographs always point beyond.

In the case of the pictures from Germany, I suppose the best way I could describe what’s going on is to say that visually, Johansson amplifies the various qualities that make Germany Germany: the country becomes an even more German version of itself. Everything that I enjoy about Germany is amplified just as much as everything that drives me absolutely crazy.

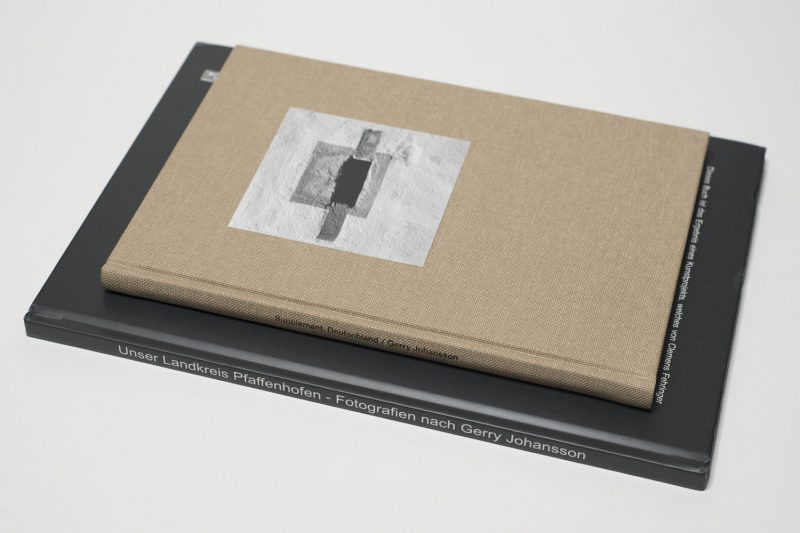

As he has demonstrated, Johansson is perfectly capable of playing the very same game with other countries, whether Sweden, his home, or the US. So there’s nothing that makes Germany a particularly good case to study. It’s just that this particular photographer is capable of acting like a visual amplifier who will turn out visual gems at an astonishing rate. “Why Supplement: Deutschland?,” asks Johansson, “Shouldn’t the 169 pictures in Deutschland (MACK, 2012) be enough? Frankly not. Some pictures I liked were left out for various reasons. And some went into the book even though they shouldn’t be there.” That works for me.

Given how simple Johansson’s approach is, it should be relatively straightforward to copy it. After all, you only need a square-format camera (or know how to crop a picture in Photoshop), and you’re in business. That’s what the members of a Bavarian continuing education photography club thought: why not photograph the area around Pfaffenhofen Gerry Johansson style? So they did. Sixteen photographers did it for a little more than a year, after the end of which they had an exhibition (German language link), and they published a book (which you can buy if you email them — follow this link, but note this is all in German).

Then they contacted the Swedish photographer to let him know. Johansson was more than pleased with the results. I know of the project through him — he sent me a copy of his new book along with theirs. “I would happily have made most of the pictures,” he wrote to me in a letter, “and I was told that they have had a good time making the pictures and that they felt they had learned something about photography.” That’s the other thing about the photographer: he not only produces visual gems at a staggering rate, he’s also one of the nicest people I’ve ever met in photoland.

Supplement: Deutschland; photographs by Gerry Johansson; 96 pages; Johansson & Jansson; 2018

Rating: Photography 5.0, Book Concept 3.0, Edit 3.0, Production 4.5 – Overall 4.1

Unser Landkreis Pfaffenhofen; photographs by various photographers; text by Clemens Fehringer; 84 pages; Fotofreunde Pfaffenhofen; 2017

(not rated)