In the world of photography, hang ups concerning graphic design are very common. To begin with, a lot of photographers think they can produce their own design, even though they have no or very little experience as designers, let alone training. In addition, especially in the US many photographers will not talk of design. Instead, they will discuss “too much design,” as if design were something that could be measured in some way, and thus as if there could be such a thing as “too much” or “too little” design. Approached that way, design instantly becomes a problem. But doing just that, treating design as a problem, is the actual problem here.

When you open a photobook, it’s designed, whether or not an actual graphic designer got to work on it or not. The arrangement of photographs and text, the choice made for the type — all of that is part of graphic design. If there was no designer, if in other words the book was put together by the photographer, more often than not the design might adhere to its maker’s idea of “just enough” design (whatever that might be). In all likelihood, the book will be poorly designed, with little (or even big eye) sores everywhere. Pictures might be placed a bit awkwardly, the type choice and setting might be grim, etc. We’ve all seen these kinds of books. And maybe it’s because we’ve seen so many of them and also know so little of what design does that we have come to accept it.

Just like photography, graphic design finds itself somewhere in the world of the arts. As much as I love photography, I could easily make the case that graphic design actually is more of an art form than photography. But let’s not even go there. So ignoring that, there is good design, and there is bad design. We might not easily be able to have an agreement concerning what is good or bad. We might have different levels of expertise to come up with the criteria or words to describe why something is good or bad. But that then simply is the arts, where we struggle equally to come to an agreement about what is good or bad in photography.

I will have to say this, though, what really, really gets me is the often open disdain reserved for graphic design that I run into in the world of photography. Just because you can download InDesign and plop down some pictures fairly easily you’re not a designer. It just doesn’t work that way. The other day, I read a book designer’s description of how what he did mattered, and there was ample talk on Twitter along the lines of “of course, a designer would say that.” Is that how you would talk about your dentist, too? “Of course, a dentist would say I should get this cavity in my tooth taken care of.”

Coming back to the “too much design” complaints when photobooks are concerned, what this comment appears to reflect, based on how and where I tend to hear it, is a combination of the following. First, many photographers are incredibly conservative, being just flabbergasted by many of the options and choices available in contemporary graphic design. So that’s a matter of taste. Which is fine. If you want to live in a barren apartment, with concrete walls exposed and no ornamentation, that’s fine. But you also want to at least have an open mind concerning other options and not dismiss them outright as “too much.”

Second, it’s often really about a photographer wanting the photographs do all the lifting. This is fair enough, even though it’s obviously no excuse to simply pretend design is unnecessary.

Third, many photographers think they need to be in total control of all aspects of their photobooks. What makes this type of micromanaging so bad is not just that such an approach to management is bad per se. It’s also that many photographers simply lack the expertise to know everything about editing/sequencing, design, and production (if you want to hear stories, treat me to a beer or two if you happen to run into me in a bar somewhere).

Lastly, the design in question might actually be bad. Obviously, that’s entirely possible, and there are many books that employ a lot of very contemporary design in ways that ruin things. Honestly, to take those extreme examples as cases against graphic design is just foolish. Plus, there are many books where the design actually enhances the photographs in question quite a bit, and cherry picking only problematic cases is not a very good idea.

So when thinking about design, or when there’s a case where you think there’s “too much,” try to disentangle what’s going on. Try to figure out to what extent these factors come together and how. Maybe there even is something else. A good way to learn more is to simply talk to a graphic designer and see what s/he might think. It’s likely you’ll be in for a big surprise.

In the world of photobooks, the issue of design is just one of the various aspects that have to be dealt with. What everything comes down to in the end is that all the elements of the book have to come together successfully without one crowding out any (or all) of the others. This concerns the edit and sequence of the photographs, the design, the production, the text, etc.

The reality is that production issues might mar a book just as easily as bad design or bad pictures. However, here photographers usually only complain about bad production (bad printing, say), while generally drooling over the most overly expensive and ridiculous looking books. Yes, you can “fuck the midtones,” say, but that won’t get you a good looking book in every case. Unfortunately, many photographers and some publishers fetishize their photobooks, without putting much consideration into whether using inks produced with minerals harvested on the moon really is necessary.

Over the course of the past two years, I had to think about these aspects of photobook making more than I previously thought was healthy, while working on a book about photobook making. But I won’t, and really can’t, complain. As far as I can tell, my health also hasn’t taken a it. I’m still not a design expert, and I have also learned that there are many things I still don’t know about production. But I know that I have to consider them, I know a lot better what to look for, and I know that if I need advice I will speak to an expert.

In general, it’s good to have these different aspects of photobooks in mind, to be able to consider more than merely the pictures, to look beyond whether, possibly, the object in question satisfies one’s own photobook fetish (whatever that might be).

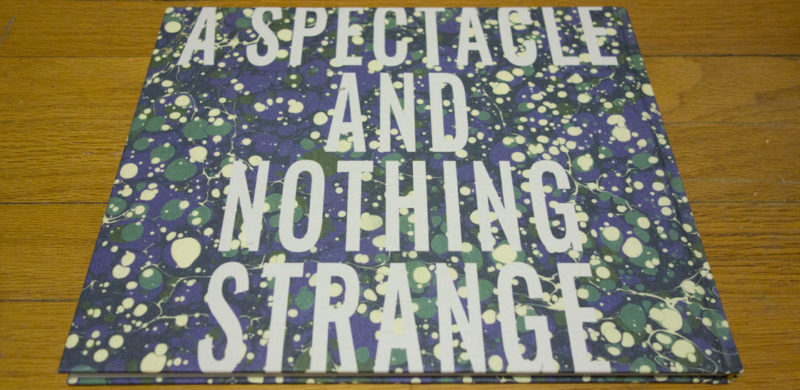

While the above might read like an impossibly long introduction for a book review, there is a clear reason why it exists here (beyond me really needing to get it off my chest). I had to consider the aspects of photobook making, in particular design, because I was looking at Ahndraya Parlato‘s A Spectacle and Nothing Strange. It’s a book that at least initially resists revealing itself easily. Whatever narrative is present is elliptical and at times disorienting. What struck me was the role design was allowed to contribute to the overall idea.

For a start, the designers made some very smart choices concerning the whole “package.” It’s a cloth-covered hardback, with a floral pattern on the cloth. There’s a picture on the front, and the title of the book is printed on its back, very large, with the text running all the way to the book’s head and tail (which I quite like). The book’s endpapers contain the book’s title (slightly abbreviated in the front) and part of the colophon plus the title page (in the back).

Inside, the book starts off with a couple of cryptic quotes, and then it’s a strange world of pictures. For the most part, the spreads adhere to the simple format of a picture on the right-hand side facing a blank page (there are no titles or page numbers). If it were just that, with the occasional pairing thrown in, I don’t think the book would succeed. But every now and then, a picture might get thrown all the way to the edge of a page, which makes for a very drastic effect (a bold and confident choice by the book’s makers, given that during production, when the book gets trimmed, you might lose a slice of your picture).

Whatever gallery-show-on-paper lull a viewer might have been in, s/he is being jolted out of it. Something is going on. What might this be? The book employs these kinds of attention-grabbing devices often enough for it, the whole, to come together. I personally don’t think the book would succeed without them, given that the photographs’ visual language tends to often be rather oblique, and it’s very hard to add up a lot of oblique photographs without having a viewer simply give up. This is a tricky path to follow.

A Spectacle and Nothing Strange is an entirely experiential book, featuring photographs depicting (or being based on) experiences and then trying to make its viewers connect. These are not experiences that can be easily conveyed through photographs. They are conflicted, at times disturbing, at times seemingly mundane. The book asks of its viewers to invest the time (well, the money first obviously) to make the connection needed to see and then feel what is going on. But there’s feeling and, thankfully, no attempts at displaying a degree of visual cleverness (which probably is my pet peeve with large parts of contemporary photography right now).

In fact, some of the photographs are disarmingly simple. I quite like that. As a viewer, you’re being kept on your toes. You don’t quite know where it’s all going. There are moments of confusion and maybe even terror. But in the end, the book offers a rewarding experience, even though it’s not even that clear what it actually is.

A Spectacle and Nothing Strange; photographs by Ahndraya Parlato; essay by Christian Hawkey; 104 pages; Kehrer; 2016

Rating: Photography 4.0, Book Concept 4.0, Edit 3.0, Production 4.5 – Overall 4.0