David Fathi is one of the winners of the 2015 Conscientious Portfolio Competition. Wolfgang, based on photographs from the CERN archives, is a slightly tongue in cheek look behind the scenes of science, using Wolfgang Pauli as its main character (Pauli might be most well known for having invented particle spin). I spoke with Fathi about his original motivation and details of this project.

Jörg Colberg: Can you talk about your background? Who are you as a photographer, what are your main interests and/or motivations?

David Fathi: My background is in science, as I studied mathematics and computer engineering. Photography and art came a little later, at first as an escape route, but quickly my geeky side came biting back. It became a vector for my obsessions around the limits of human knowledge.

In my artistic practice I start working with weird facts about science, politics, history, psychology and try shining a different light on them. I hope that using and illustrating small absurd stories helps comprehend larger abstract ideas.

JC: For Wolfgang, you used images from the CERN photography archive, and you then manipulated them. How did you come across that archive? Where did the idea for the project come from?

DF: The archive is all accessible online. It started a little over a year ago, when CERN realized that they had a huge archive of photos spanning from the end of the 1950s to the late 80s, but did not know what was pictured in most of them. So they asked the general public to crowdsource their knowledge, if they knew what was pictured, who was photographed, anything. Maybe scientists working in that field, maybe relatives could help.

The photos are amazing, they look like science-fiction, but are just science from 50 years ago. My goal wasn’t to just curate some esoteric selection of scientific weirdness, but to search for some story that I could grasp, in line with my own artistic work and obsessions. I found a way to batch download every single photo available. They are still scanning the archive as we speak, but at the moment I have browsed through 120,000 photos.

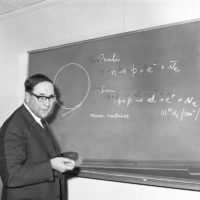

When I started looking through the images, I stumbled upon a few which mentioned someone named Wolfgang Pauli (on a blackboard, or a memorial plaque). I didn’t know who he was at the time, even though he is actually one of the founders of quantum physics, and he was seen by his peers as Einstein’s successor. I did a bit of research on him, and that’s when I first heard of the Pauli Effect. They’re anecdotes according to when Wolfgang Pauli entered a room experiences would fail and machinery would break down.

Pauli actually believed in this effect and used it in his correspondence with Carl Jung as examples of the idea of “synchronicity”, a Jungian theory that events can be related by meaning instead of causality.

I had a lot of difficulty understanding how one of the greatest minds in science would also believe in a theory that sounds like pure superstition.

But then I started thinking about quantum theory, and how the greatest scientific minds can come up with theories of elementary particles that seem totally at odds with the macroscopic world we live in. Quantum physics is non-intuitive, and the implications of how matter can behave on a subatomic level can send chills down the spine of any rational being. The trailblazers in science often theorize on the craziest ideas, and seeing them as stuffy, old, rational professors is kind of an invention of the second part of the 20th century. After the Second World War, science needed to be rehabilitated, as the image of the scientist was quite frightening, given Nazi medical experients or the creation of the atomic bomb. So it was reassuring to see science as an objective practice without emotion or chaos – even though science is anything but order.

So I wanted to confront science and myth and represent their battle through the comical “Pauli Effect”. I imagined a semi-fiction where Wolfgang Pauli, who died shortly before the beginning of the archive, continued to haunt everyday life at CERN.

JC: Can you talk about your process of going through the archive? How did you decide which pictures to pick?

DF: The photos I show can be classified in three general categories :

Pauli’s presence: I search throughout the archive for any photos where Wolfgang Pauli’s presence could still be found. I found his name on road signs (streets at CERN are named after famous physicists), blackboards, books, etc. I found photos of the inauguration of his bust, with his widow attending the event. I found photos of the “Salle Pauli”, the commemorative room named after him.

Weird experiments: Scenes that seem to be at the crossroads of science and fiction. Research in quantum physics is often a crazy endeavor, and CERN released this archive because they didn’t know themselves what was going on in a lot of the photos.

Accidents: As if the Pauli Effect still was at work. Accidents can be of different nature; the photographed result (a car accident, a broken machine), an ambiguous scene (a man hanging from a ledge, a box in midair), the photograph itself (double exposure, damaged negative), or even the scanned archive (corrupted photos)

But for any of these categories, some photos are totally true, directly extracted from the archive, while others are manipulated by me.

JC: And how did you decide about how to manipulate the images?

DF: The manipulations are made to blur the line between fact and fiction, and to make the viewer a participant in the outcome of the photos.

In quantum physics there is an important principle called the “Observer Effect”. The act of observation fixes the outcome of the scene. As long as a particle is not observed, it exists in a linear combination of multiple states. I like the parallel in the act of photography, which in a way also fixes the outcome of a scene.

So for this project, the aim was for the spectator to act as an observer. He or she is the one deciding what is true and what is false, what is science and what is myth.

But often, fact is weirder than fiction. One of the photos I found in the archive is an accident where a cinder block falls off a truck, right next to a road sign with the name of the street “Route W. Pauli” (Pauli Road). That photo is 100% real, and I couldn’t have dreamt a better illustration of the Pauli Effect!