Lucy Levene is one of the winners of the 2014 Conscientious Portfolio Competition. I picked her submitted body of work for the following reasons:

“I actually still haven’t quite figured out why or how The Spaghetti Tree keeps such a strong presence in my mind. That, ultimately, is the sign of good photography: it will stay with you and keep asking questions, instead of providing superficial answers. With The Spaghetti Tree, Lucy Levene not only shows her skills as an image maker, she also displays a profound understanding of photographic conventions, which, when played against each other, keep irritating the viewer, to confound expectations.”

In the following conversation, I spoke with the artist about her background and about the thinking behind the work.

Jörg Colberg: Could you give us a little background of yourself, both as a person and a photographer?

Lucy Levene: I grew up in North West London in a predominantly middle class Jewish community. Both my parents ran their own businesses and neither were religious, however Jewish Identity was very important to my mother in particular. I came to photography through fine art, studying art and history of art at school. I loved observational, figurative work and at the time, after a foundation year at Edinburgh College of Art, photography rather than painting seemed to me to be the natural medium within which to explore this. I studied for my BA in Edinburgh and then for my MA at the Royal College of Art in London.

JC: Concerning your project The Spaghetti Tree, which was selected as one of the winners of the competition, you write “As an outsider working within this community, I became interested in the tensions between between public and private, formal and informal and in how these disparities relate to construction and accident within photography; the perfect and the imperfect image.” Could you expand on this a little bit?

LL: The Spaghetti Tree was my response to a commission from the 1000 Words Magazine Photography Award. The award was part of a larger initiative that was supported by the EU Cultural Programme. As such, the subject matter was very specific. The photographers involved were invited to make work that would contribute to an archive that explored and documented the migration that occurred in the decades after WWII, from Southern to Northern Europe. I was therefor very much led to this particular project through the specificity of the brief.

My own experience of migration is one of being a third generation Jewish immigrant (my parents’ families left Eastern Europe at the beginning of the 20th Century). I am very interested in assimilation, in particular in the absurdities and contradictions that can arise; the desire to preserve cultural individualities is often at odds with the need to assimilate. So this was my access point to this work and on a personal level, I was drawn to this community that seemed both so well integrated and yet distinctly separate.

I had previously approached the subject of assimilation through my own community and had reservations about attempting to portray this community when I have so little experience of Italian culture. These reservations became central to my working process, and I wanted to make a piece that had an honesty to it and wasn’t trying to assume a knowledge of the community that I didn’t really have. I allowed myself to be led by the people I was introduced to, photographing what was suggested to me and attending events at which I was invited to photograph. I was aware of my own assumptions about Italian culture, mostly based on film and TV stereotypes and was curious as to the extent to which some of the younger generations may have adopted the same ideas from the same sources.

My interaction with the community felt like a bit of a dance. Tensions arose between what the people within the community wanted me to record and what I hoped to achieve and there was of course a strong division between public and private. What was being shown to me was constructed, formal and public; I was attending community events that were very outward facing, rather than interior domestic spaces, predominantly. And so I began to look for private moments and moments of informality within these public displays.

Christenings and community dances can of course be very theatrical events. Like the nightclubs at which I’ve previously photographed, as participants, we are there to be looked at and, on occasion, recorded. Photographically, I was looking for gaps within the constructions, finding unexpected moments within a constructed portrait set up for example. I get frustrated with my work when it is too aesthetically clean – I feel that the viewer can slip off the surface of the images and I also hoped to disrupt this too by introducing messy and unexpected visual elements.

JC: Earlier, you speak of an “objective democracy” – what is that? I’m curious how your approach to making this work was shaped, which, it seems, at least in part appears to derive from a frustration with the medium itself.

LL: I realized that intuitively I make a lot of my visual decisions in order to eliminate perceived subjectivity. For example, I might use a very flat flash to light up every area of the scene in order to avoid the sentimentality of a more emotive lighting, and to avoid drawing the eye to one particular area. Equally my images are often taken from a central face on point of view which flattens the scene. This also contributes to an appearance of objectivity. Both of these ways of looking aim to avoid creating a hierarchy of visual importance within the image. So I am looking for a democracy within the scene, and one which has the appearance of objectivity.

JC: I’m not sure I’m following, given that your decisions to achieve these photographs are based on very subjective decisions. Maybe you can help me understand what you’re after here by telling me why you want to eliminate what you call perceived subjectivity?

LL: I think this is an approach that I take generally within my work rather than one that is specific to this project. I guess it comes down to the discussion around the photograph as ‘evidence’, documentary photography in particular. By photographing in this manner, I am looking for something that I feel is closer to the truth of the situation (rather than my truth).

In this work, rather than wanting to eliminate subjectivity, I wanted to play with elements of fact and fiction within the work; to create work with an appearance of objectivity and then undermine that by revealing elements of construction. I wanted the audience to double take – to disrupt their expectations and lead them to question the structure of what they are seeing.

JC: I’m curious: What is truth in photography for you?

LL: An exploration of ‘truth’ is central to my ethos and to my way of looking. I am becoming more and more aware of how truth is constructed by our own personal narratives; how we construct narratives to give structure to events and how different people can of course experience the same event quite differently.

And yet despite this awareness, there is still a desire to scrape back all of these layers of perception to access something ‘real’ or truthful. I find this contradiction reflected within photography. Academically, we dismiss the idea of ‘photographic truth’ and yet there is still an intuitive belief response to certain forms of photography.

In this work I wanted to play with those forms of photography, to foreground elements of construction within some but not all of the images, in order to emphasize my intervention and make the viewer question the truth value of the documentary form.

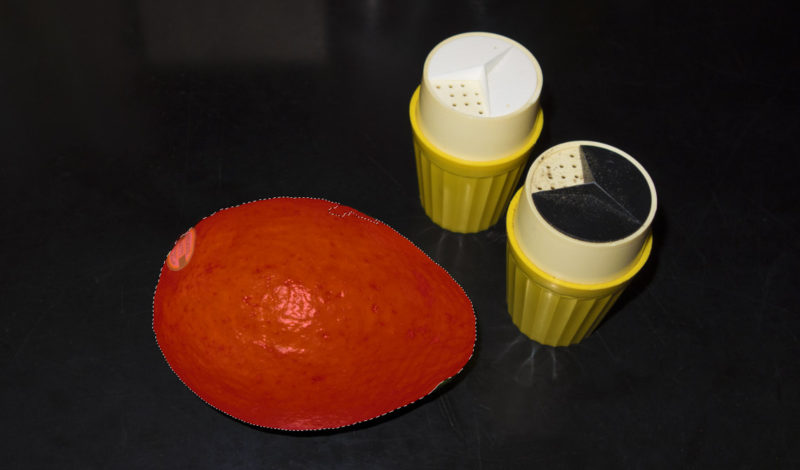

For example in one image (‘Empty Hall 1’) the subject of the image is my flash reflected in the wall. In a pair of images of orchids within the church interior, one image is taken with daylight and the same image retaken with flash. The emotional effect of each image is very different and I felt that as a pair of images, they highlight the simple artifice of photography. In some of the formal portraits, the background stands and the room behind them are visible, again emphasising the nature of our encounter.

With portraits in particular, I often feel that portraits can appear to portray a moment of intimacy between the photography and the subject, whereas the reality of the encounter can be quite different; rushed, impersonal etc. I hoped that the caught, ‘accidental’ portraits would make people question their assumptions about the more expected portraits. This combination of approaches felt like a more honest representation of what occurred.