The pile of photobooks still be to be reviewed next to my desk has reached towering proportions. So I thought I’d start the New Year trying to decrease its height. I realize that this site has become somewhat photobook centric, but that might just reflect the fact that currently, photobooks are driving the medium’s discourse. After the gigantomania of Düsseldorf School-style photographs on the wall, it’s certainly a relief to be able to talk about something that can be enjoyed by a much larger audience in all kinds of ways. It’s not clear whether the flurry of publishing we’re currently witnessing will last, but let’s enjoy it while it does.

Like pretty much everyone I talked to, I enjoyed Simon Menner‘s Images from the Secret Stasi Archives (find my review of the book here). But, and this has become an increasingly important problem for me, while it’s fun to look at those often absurd images, their display as oddities, as if taken from a goofball comedy the likes of which Hollywood loves churning out, takes away from the fact that the organization behind them, East Germany’s Ministerium für Staatssicherheit (with its official abbreviation MfS and its unofficial one Stasi; translated Ministry [Agency] for State [National] Security) was not goofball at all. Quite on the contrary. So essentially having a laugh at the expense of those left to rot in Stasi prisons feels wrong, even if that’s obviously not Menner’s aim.

A more recent book, Arwed Messmer‘s Reenactment MfS , has now upped the ante considerable in multiple ways. For a start, the book centers on the role of photography, both in the Stasi context itself, as in the larger context of how we look at and/or deal with photographs. Conceptually, the book itself also pushes the boundaries. Apart from a title page, several pages in, there is no text at all, only pictures. Where those pictures might be coming from isn’t always that obvious. Some very obviously look like crime-scene photographs. Others could have come straight out of Menner’s book. Still others look like they were taken by Messmer. Violence abounds, whether in a staged or documented form, and it can be physical or psychological violence.

, has now upped the ante considerable in multiple ways. For a start, the book centers on the role of photography, both in the Stasi context itself, as in the larger context of how we look at and/or deal with photographs. Conceptually, the book itself also pushes the boundaries. Apart from a title page, several pages in, there is no text at all, only pictures. Where those pictures might be coming from isn’t always that obvious. Some very obviously look like crime-scene photographs. Others could have come straight out of Menner’s book. Still others look like they were taken by Messmer. Violence abounds, whether in a staged or documented form, and it can be physical or psychological violence.

For those eager to get explanations, there is the Appendix in the form of a booklet to be found in a pouch at the end of the main book. In it, the sources of the images are revealed. So you learn about what it is you see in the various pictures, such as, for example, on page 77, “Reenactment of an escape attempt with escape helper (right) and escaper in the trunk of a Volkswagen K 70 L, July 17, 1972.” In other words, a person caught in an attempt to flee East Germany and arrested with his helper, was forced to crawl back into the car’s trunk so that the Stasi could take a photograph. The things you can do with pictures…

So Reenactment MfS forces its viewers not just to come to terms with the East German secret service’s utterly deplorable methods, but also with how photography itself became if not an accomplice then at least a very useful tool. Of course, if you are familiar with the history of photography, you will know that photography has always played this role, whether it was in the othering of cultures deemed primitive, in cataloguing those who would be killed right after, etc. Given that photography has been such a useful tool for such terrible purposes, this ought to tell us something about the medium. If we did not believe it to have such potent properties, we might not find the medium in these terrible parts of human history.

Seen this way, Reenactment MfS is possibly one of the most ambitious and potent ways to deal with the photographic Stasi legacy. It aims at revealing the cruelty of the organization itself, asking us to reflect on how our own agencies might be involved in similar schemes. At the same time, it points its finger at photography’s core, which would be completely hollow if it weren’t for our willingness to believe what we see, provided it is presented in specific ways. This is conceptual photography at its very best. Highly recommended.

Reenactment MfS; archival images plus photographs by Arwed Messmer; texts by Annett Gröschner, Matthias Flügge; 146 pages plus booklet; Hatje Cantz; 2014

Rating: Photography 3, Book Concept 5, Edit 5, Production 4 – Overall 4.1

Now that the Düsseldorf School craze is over, we are presented with the opportunity to evaluate its impact and, specifically, the artistic merit of its various artists. I personally never believed that there was really so much that would unite those different photographers once you moved beyond print sizes, presentation, artistic provenance, and possibly the fact that they are all German citizens. Of the Düsseldorf photographers, Thomas Ruff has long been my favourite. He was and still is one of the very few contemporary photographers intent on exploring his medium in a way that would happily throw out whatever orthodoxy there was to be (and still is) to be encountered (vast parts of contemporary photography remind me of the Vatican in their unwillingness to stray from long-established dogma that, in reality, has long stopped to make much, if any, sense).

There is no dearth of books around Thomas Ruff’s work, including various surveys. Oberflächen, Tiefen is a favourite of mine, an intensely smart and well produced book printed on newsprint. As an artist, Ruff is unusually productive, churning out new work apparently without much effort. Survey books thus rapidly become lacking in the newest work. Of course, the question is whether adding a new series or two truly justifies another survey. Turns out that the idea of the Ruff survey has not been exhausted at all, as is shown by the new Editions 1988-2014 . The photographer well known for his monumental prints has been producing a plethora of much smaller prints in larger editions, often using fairly uncommon photographic printing processes. This new survey is a catalogue raisonné of those smaller editions.

. The photographer well known for his monumental prints has been producing a plethora of much smaller prints in larger editions, often using fairly uncommon photographic printing processes. This new survey is a catalogue raisonné of those smaller editions.

Presented chronologically, Editions 1988-2014 introduces all of Ruff’s bodies of work, many of them not that well known. But the editions don’t necessarily follow the time when the work was made, so “older” images keep (re-)appearing. As a consequence, the viewer is given a chance to see seemingly very different photographs, even processes, next to each other, resulting in a much deeper understanding of what Ruff is actually after. Seen that way, the book reveals the true extent of Ruff’s photographic universe, and it makes a strong case for this artist being the possibly most relevant Düsseldorf School photographer. There really doesn’t appear to be any direction Ruff can go that would result in a dead end (compare this with Andreas Gursky’s artistic implosion after the satellite images of the planet’s oceans).

Yet again, the publisher, Hatje Cantz, have spared no expenses and have given the book the perfect form. In a day and age where there is almost a cult of self publishing (which, let’s face it, ultimately is the truest form of vanity publishing, its various merits notwithstanding), Editions 1988-2014 demonstrates what it is that publishers can do, and can do incredibly well. And as an added bonus, you get an essay about Ruff written by Thomas Weski. It really doesn’t get any better than this.

Editions 1988-2014; photographs by Thomas Ruff; texts by Thomas Weski, Valeria Liebermann; 180 pages; Hatje Cantz; 2014

Rating: Photography 5, Book Concept 5, Edit 3, Production 5 – Overall 4.7

According to its website, the project This Place “explores the complexity of Israel and the West Bank, as place and metaphor, through the eyes of twelve internationally acclaimed photographers.” The complexity – that’s a rather euphemistic way of talking about an occupation that has been going on for decades and that has been violating a plethora of international laws for as long, not even to mention the horrible amount of violence that has resulted as a consequence of all of this.

The complexity. Right. So how do you show this complexity? From what I gather, a lot of people are tired of seeing the same endless scenes of violence emanating from the area – as if making the pictures of violence go away does anything to change their underlying causes. It is as if new insight somehow can be or should be gained into situation that to many observers is clear and obvious enough. But in another sense, the situation is indeed not frozen at all. The occupation of Palestinian territory is expanding with time, and the area’s occupants are, as well. Attitudes have been changing. The area’s structural and physical violence have resulted in increasing amounts of mental violence (which, in turn, has resulted in yet more physical and structural violence – a feedback loop that, among other things, is sustaining Putinesque characters in power).

One would imagine that a medium that can only depict surfaces would be unable to show mental violence. But a camera becomes a very powerful tool in the hands of a master photographer. Any single photograph is unlikely to achieve that goal, other than maybe in a superficial, if not cartoonish sense. But a collection of photographs – that’s something entirely different. Add a little text here and there, and you’re in business. In a nutshell, this is Them by Rosalind Fox Solomon, diminuitive in form, yet incredibly powerful given what it does and how it does that.

The book was one of the main photobook surprises for me last year. In a sense, the book indeed “explores the complexity of Israel and the West Bank.” It brings the mental violence that has been produced to the very center of the stage. The majority of the photographs in Them are portraits of people whose names and origins aren’t revealed. Intermingled are short snippets of text, quotes maybe overheard or somehow uttered in front of the photographer.

The cumulative effect of viewing the photographs and reading the text is sobering, speaking of a situation that, in principle, simply isn’t tenable any longer, that, however, has been frozen in place and that will be frozen in place for a while it seems. If violence begets violence, as it clearly does, and cycles of violence have been going on for so long that any explanation merely amounts to ideology, then only a radical shift in thinking will be able to bring about a change for the better – the kind of change in thinking comparable maybe to the sudden enlightenment to be found in Eastern religions.

Them very forcefully calls for just that.

Them; photographs by Rosalind Fox Solomon; 144 pages; MACK; 2014

Rating: Photography 3.5, Book Concept 5, Edit 3, Production 5 – Overall 4.2

On my first trip to Italy, well over a decade ago, much like every visitor I was struck by the country’s beauty. The Italian friend I was visiting, however, appeared rather less smitten. Part of his disenchantment might be dismissible, given most people appear to have a beef or two with their own country (and those that don’t – boy, you want to stay away from them!). But in many conversations over delicious food and wine, I was told of a different Italy, one of disfunction, incompetence, and corruption, a country whose citizens have long given up doing anything other than trying to get through the maze of life without getting bothered too much.

Things got pretty cartoonish soon after in Italy, once the reign of Silvio Berlusconi became more and more absurd, bringing all the various things my friend had told me about out into the open. I’m still incredibly enchanted by Italy – how could you not be? But every time I visit I look out for signs of what I had been told about on that very first visit, signs that are actually not that hard to find.

I suppose if you are surrounded by traces from more than one glorious past, contemporary life has a hard time living up to what appear to be standards of the past that seem almost impossible to reach. Those traces are included in a great many of the photographs in Federico Clavarino‘s Italia O Italia, one of last year’s various surprise discoveries. There is an element of tunnel vision to those images. In a sense, all photography is the result of tunnel vision, depicting whatever often relatively small fraction of the world someone decided to devote her or his attention to. But Clavarino’s tunnel vision feels tighter than most people’s, bringing often very irrelevant seeming snippets into focus.

Italia O Italia is thus the equivalent of a mosaic, with the larger picture being made up of very small parts, each monochromatic (figuratively speaking, not literally). What this all adds up to is hard to say. Some sort of Italy, but certainly not the one from tourist brochures or TV travel programs. It’s closer to the Italy my friend spoke of, an Italy at constant odds with itself, and seemingly frozen into eternal stagnation (much like any of the sinner’s in the innermost circles of Dante’s Hell), in part by its inability to live up to any of its pasts.

Italia O Italia; photographs by Federico Clavarino; 136 pages; Akina; 2014

Rating: Photography 4, Book Concept 4, Edit 3, Production 4 – Overall 3.9

I have always wondered how long it would take before someone embraced, not rejected, the various artifacts produced by digital cameras. Film grain, after all, informs various movements in photography. Digital grain, however, is being shunned. So I was glad to see Fosi Vegue‘s XY XX, large parts of which work with the various artifacts the digital medium has to offer. The main reason why most people shun digital artifacts is because they dissolve the image in a way that requires work from the viewer. Needless to say, this is incredibly fertile territory for art.

That said, I do think that it was a mistake to give away what the images in XY XX actually are (photographs of prostitutes having sex with their clients). For a start, it’s hard to get away from Merry Alpern’s Dirty Windows , which pretty much occupied this particular territory: it’s just very hard to think of what else one could possibly say with these kinds of pictures (assuming that’s the idea, to take things a bit further).

, which pretty much occupied this particular territory: it’s just very hard to think of what else one could possibly say with these kinds of pictures (assuming that’s the idea, to take things a bit further).

I don’t think this new attempt goes beyond Alpern’s work at all, which is a bit of a shame, because in a sense, XY XX is trying to have it both ways. There are images that are hard to make out and that clearly speak of something possibly carnal or disturbing. And there are Alpern-style images of people having sex. These two go together, but that’s really the problem here: I actually don’t want to necessarily be told what I’m looking at in the more abstract images, since they operate in my mind in very different ways than the others. The specificity of the sex images reduces the abstractions produced by the digital artifacts to essentially a game of design, and that’s too bad.

What is more, given the nature of the photographs and given it’s being spelled out so clearly here, I’d personally would want a little more than a mere depiction. Instead of repeating what I wrote earlier, the interested reader might simply read an article I published about a year ago. In a nutshell, given it’s 2015, there simply is too much politics involved in this particular topic, politics both in societal and photographic terms, and I don’t think you can run away from that so easily.

XY XX; photographs by Fosi Vegue; 108 pages; Dalpine; 2014

Rating: Photography 2, Book Concept 1, Edit 3, Production 3 – Overall 2.1

Ever since the Soviet Union fell apart, photographers have been touring its hinterlands (turned countries, many of them “-stans”), looking for whatever the detritus found there might say either about the former empire or about the prospects of its local predecessor. I’m currently in the process of writing a longer piece about what large parts of this might mean, so I’m reluctant to start the fireworks just yet. Ultimately, the various photography projects (and books) might end up telling us more about the medium and/or our culture than about the places in question.

There are a few bodies of work, however, that are noteworthy, Mila Teshaieva‘s Promising Waters being one of them. Photographed in Azerbaija, Kasakhstan, and Turkmenistan, the book looks into places around the Caspian Sea, for the most parts using the detached visual language so common in contemporary photography (Lewis Baltz in colour, but barely). Honestly, the book wouldn’t nearly as interesting as it is, if the photographer hadn’t broken with that language often enough.

being one of them. Photographed in Azerbaija, Kasakhstan, and Turkmenistan, the book looks into places around the Caspian Sea, for the most parts using the detached visual language so common in contemporary photography (Lewis Baltz in colour, but barely). Honestly, the book wouldn’t nearly as interesting as it is, if the photographer hadn’t broken with that language often enough.

So there are all those signs of something going on that escapes simple messages (press snippet: “The battle for control of the region’s vast oil and gas reserves and the search for a national identity have led to far-reaching changes for the population, the environment, and general social values.”) and that speaks of a life that is more complex than for it to fit into easy templates. I tend to tell my own students to avoid talking of such things as “national identity” or “general social values” in their work, because, let’s face it, outside of academia and NPR’s All Things Considered, those terms have no life whatsoever.

Promising Waters has considerable life, and the contrast between some of the photographic conventions and what is breaking through, to assert its own life, is what makes it. With short pieces of text added smartly in the flow of the photographs, the book tells us a story that is more universal that you would imagine, a story that could – and does – play itself out in other places as well.

After all, ultimately, you live your life, wherever you are, against all the odds, simply because you just do. There might not be any promise, at least promise in the form of something tied to the terms mentioned above, but that’s the real life: the promises many of us live from are those tied to something that in the grander scheme of things doesn’t really matter. That’s what makes us human.

Promising Waters; photographs by Mila Teshaieva; essays by Maya Iskenderova, Christoph Moeskes/Mila Teshaieva; 120 pages; Kehrer; 2014

Rating: Photography 3, Book Concept 3.5, Edit 3, Production 3 – Overall 3.1

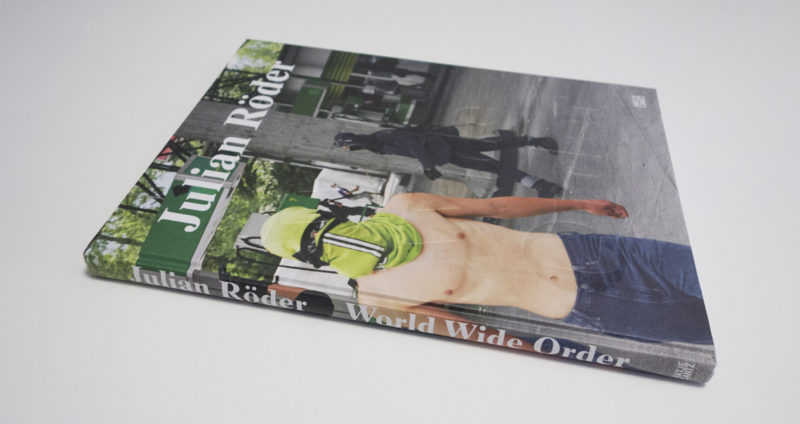

, Julian Röder focuses in on his approach to photography by setting himself apart from widely held beliefs. It’s a statement worthwhile to be quoted in full: