I frequently run into being asked by photographers how they can become better at writing about their own work. This is not an easy topic to talk about, certainly not without using specific examples. But I thought I’d do so anyway, in the hope that those who are interested in it might get something out of it.

Before going into any of the details, I will have to make a disclaimer: I wrote a piece about statements before. The following, just like this previous article, inevitably is based at least to some extent on my own personal preferences as someone who reads a lot, who writes a lot (mostly about photography), who looks at a lot of photography, and who teaches in a graduate photography program. Whether there is a perfect recipe for how to approach writing about one’s own photography is not clear. What is clear, however, is that you will want to keep in mind whatever biases and/or preferences you have detected in my writing already.

I will also have to make an assumption: I’m assuming that you, the photographer, want to be understood. In other words, I’m assuming that you have an interest in writing something that not only talks about your work in a smart and engaging way, but that also can be understood by a large variety of people, including those who do not hold advanced philosophy (or other obscure) degrees. If that is not the case, if, in other words, you like your highfalutin art speak, you needn’t read any further.

How do you write about your photographs? For a start, you will have to be able to have a long, hard look at the pictures. And you will need to start writing about them before it’s all done. Don’t approach writing about your photographs by making them first, and then getting to writing about them. That’s not a good idea. Instead, take photographs and write. Look at what you have, both in terms of pictures and of writing, and see what works. Constantly re-evaluate what you have. Don’t try to have the photographs conform to your writing (unless you’re working on a completely conceptual body of work).

If what you’re writing about is not in the pictures you’re in trouble. Just like your (already existing) pictures need to inform the future ones, they also need to inform your writing.

But writing about something that’s not in the pictures teaches you a lesson: your ideas of what you’re doing might be off. That’s not a problem at all. In fact, provided you’re open to the possibilities offered to you it’s an immense gift. Projects often evolve in ways that cannot be foreseen. Be open to those possibilities – that’s where you can find more (and often better) photographs, and that is also where you can find the basis for your writing.

At the same time, have a good look at what you’re writing, and try to figure out why it’s not in the pictures. The idea is not necessarily to bring it to the pictures, but to understand what’s going on. Your writing might reflect, for example, points of resistance, points of hesitation. Seeing those in writing can help: Wait, this is me? Why am I hesitant to approach this particular aspect? What can this tell me?

The clearer your understanding of what you’re doing becomes, the easier it will be to take photographs and to write about them, but also to edit them.

I’m a firm believer than good editing requires a thorough understanding of the photographs in question. That understanding might be mostly subconscious. Good photo editors are good photo editors because they can pick up on what’s in the work in almost no time, creating edits that very quickly feel a lot more coherent than the unedited original set. How these photo editors do that is not that clear. I enjoy editing photographs, and I usually find it easy and straightforward; but I often have a hard time talking about it in a generalized way. You have to be very open and susceptible to the work.

This is, in part, why photographers usually are such lousy editors: Being open and honest with oneself is very, very hard, even if one has the best of intentions. Here, having developed a deeper sense of the work through writing helps. If you can write about your work in all likelihood you will be able to produce a good edit as well.

For photography, writing always has to start from what is in the pictures.

I’ll say it again: If what you’re writing about is not in the pictures you’re in trouble (even if the writing sounds so good).

That being said, don’t write about what’s in the pictures. Do not describe your photographs. You will have to realize that your viewers are not blind.

Also realize that in all likelihood your viewers are not stupid. Do not explain your photographs.

One of the problems many photographers appear to have is that they think they’re somehow required to write illegible gobbledygook. I don’t know where that idea might be coming from. Maybe from many atrocious artist statements already out in the world, often used by galleries or photobook publishers to advertize their wares? It’s possible. Maybe from too many photography curators using jargon to embellish their own work? Equally possible. The reality is, though, that nobody requires you to write nonsense. Nobody expects you to try to impress people by embellishing already poorly written text with pseudo-intellectual jargon and references to French philosophers. Actually, if your gallerist tells you that’s what they want, you might want to look for better representation.

What to do, though? How to approach writing? As I noted, you don’t want to start at the very end, trying to add some words to a finished project. Start writing while you’re in the middle. Every photographer should write (and read – a lot). The act of committing thoughts to paper – or hacking them into a computer – is more liberating than you’d imagine. You are probably only going to use a small fraction of all the writing, but you will be surprised what your subconsciousness can come up with – the same subconsciousness that’s responsible for so much in your photographs.

My general advice for photographers always is: write using a simple, clear voice – your voice. What gets conveyed in the pictures should get conveyed in the writing. So you have to be aware of what your pictures do and how they do it, and you then have to be able to bring that to your writing. In each case, the way to do that is to practice a lot. Do it over and over again, and don’t be afraid of making mistakes.

Have your writing evolve along the pictures. Have it be informed by the pictures and, possibly, inform your pictures. There has got to be a balance. If in doubt, it’s your pictures that matter, though.

The beauty of a false start, of a failure, is that it’s a start. It moves you to a different place. If it feels wrong, there is a chance to learn something. Figure out why it feels wrong. That will tell you something about your pictures (and, by extension, about your writing).

The form of the writing should follow the form of your work. That’s almost too obvious to point out, but it’s amazing how many people don’t take this to heart. If you have a very poetic series of photographs, why not write about them in much the same way?

The interaction between writing and photographs is tricky. What I’ve found is that people let their viewing of photographs be guided by writing. In other words, they read a statement, and if they don’t see what’s in the statement they then complain about the pictures. This tells us two things. First, people somehow trust words more than pictures. Second, people are very good at picking up on a mismatch between what they read and see.

Thus, writing about your photographs boils down to making sure any mismatch disappears. People will pick up on that mismatch right away. You can try to hide it with art speak or quotes, but people aren’t stupid – they’ll see that you’re trying to get away with something.

Of course, someone might look at the pictures first and then read the text. This gives your pictures a much better chance to work on their own. But if there’s a mismatch it’ll still be noticed.

How do you write about your work then? Let’s assume you’ve written down texts or phrases or whatever else along with your shooting. If you have done that, it’s very likely you’ll find writing much easier. The closer you are to understanding your images on a photographic level and on the written level, the closer you’ll be to getting the right text done.

Let’s assume you haven’t written about your work (for whatever reason). The rules so far were: no art-speak bullshit, no explaining, no describing. Fourth rule: absolutely no NPR speak. NPR is good for what it does – provide interesting subject matters in a way that won’t upset anyone and leaves everybody just a tad bit better informed. But you don’t want that for your writing. Don’t try to make everybody happy. Don’t try to cover all your bases.

This is not to say that your writing needs controversy. It doesn’t. It might, though. And if it does, it needs to be there. It’s up to you to figure it out. In order to do that you have to know where you’re coming from. What do you care about as an artist? And what do you want people to care about?

Provide an answer to the following question: Why should I, the viewer, care about your pictures?

As a photographer, it is your responsibility to make people care about your work. In other words, do not expect people to care! And do not chide people for not caring about something you care deeply about! Instead, make them care! Of course, your photographs always will have to do the heavy lifting. But you can help them a little, and your writing can be part of it.

Mind you, your job is not to be a marketing person. If we assume that you care about your pictures, then it seems obvious that you’d love if other people cared as well. Show people how you care about your photographs; but don’t be a phony. No marketing speak. Again, resist the temptation to write in a way that will appeal to as many people as possible. You’re not in the business of selling soap.

The fact that you care about your photographs is crucial. If you don’t care about your work why do you even bother? Why should I care if you don’t care?

Given you care about your work, there are some commonly used phrases and words you want to avoid like the pest. Here’s one: interesting. Never, ever say you worked on a body of work because you found it interesting. People find all kinds of things interesting, yet they deem very few of them worthwhile to give them the attention a fully realized photography project requires. It’s one thing to be interested in something, it’s quite another to have the fire in one’s guts to work on that for a long time. Where’s that fire coming from?

For the love of God, please don’t tell me you’re investigating or exploring something with your pictures! You’re not. You’re not a scientist (unless you are literally one, in which case you publish the work in a scientific journal). There’s really nothing wrong with scientists (after all, I was one for years). But when it comes to your pictures, your art, the last thing you’re probably doing is investigating something. You’re no disinterested observer following widely accepted rules that strive to result in as objective an observation as possible.

Your pictures are not about something. OK, they are, all pictures are about something. But your statement is the last place where you want to spell that out. After all, good work that is about something also has something at stake. And that’s where the juice is. What’s at stake in your work? Don’t explain that (remember, no explaining). But whatever is at stake is a good basis for a statement.

The reality is that not everybody is going to care or even going to like your pictures. That’s just the way it is. So don’t worry about that. When writing about your work, don’t worry about pleasing everybody (as I said no NPR). Instead, write to please yourself first. If you do that well, you will please the same people who will like your pictures.

In other words, just like when you are photographing you will have to trust yourself first, and you then have to have the faith that your pictures and writing will speak to the right people.

A good approach to writing about your own photographs is to write around them instead of about them. As I noted earlier, your viewers aren’t blind, so don’t tell them what they see. Don’t tell them what you want them to see, either. If someone doesn’t see that, but something else – then what? Do you want to limit what people can get out of your pictures?

Writing around your pictures means producing a piece of writing that conveys very similar ideas than your pictures, albeit in other ways. Maybe you’ll add some things that are inexpressible in pictures. Writing around your pictures means that you’ll add a bit of your own personality, of where you’re coming from. You’re going to be showing your viewers a different angle from which they can approach you (and the work).

If you look at how many well-known photographers present their work, many of them talk around them, instead of about them. In fact, a lot of photographers are very reluctant to talk about their pictures, because it takes the magic away. You will have to be a little bit like a (real-world) magician, a large part of whose trickery relies on shifting the viewer’s attention elsewhere. Because photography seemingly is so descriptive, many photographers have a hard time doing that. But that’s where you can find the art of photography.

Lastly, always get an honest opinion from a few people about your work, whether it’s the photographs or the writing. Needless to say, avoid using loved ones and/or family members unless you can be 100% sure they’re going to be honest with you (in much the same way, avoid people who can’t be critical for whatever reason). That being said, don’t try editing by committee. That’s not going to work. Get honest feedback from people whose opinions you appreciate and trust, and then incorporate that into your work.

As I already noted, there is no general recipe for how to write about one’s photographs. There is no general recipe for how to take pictures, either. But the preceding contains many pointers that I hope can help you approach writing about your pictures. It really is not nearly as hard as you’d imagine. As long as you keep it simple, as long as you remain close to yourself, as long as you resist the various temptations (again: no explaining, no describing, no art speak, no meaningless generalities) you will be fine.

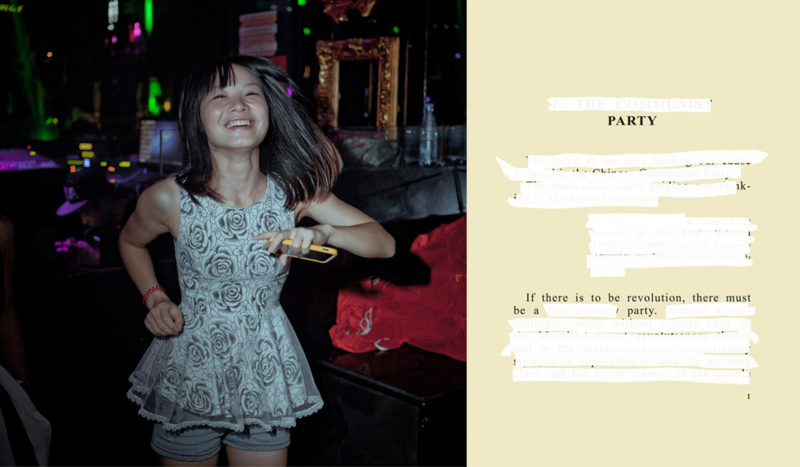

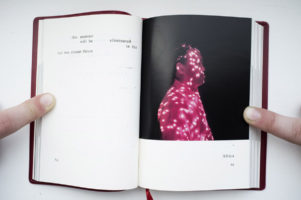

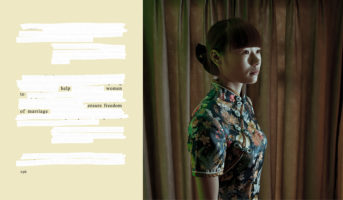

). How do you then adequately go about the “little red book”? Well, for example, you white out most of the text so that what is left is “people can talk much nonsense” (p. 212), “the real heros are ignorant” (p. 118), or “intellectuals tend to be thinking” (p. 292). I’m tempted to think the artists organizing Berlin’s 1920 Erste Internationale Dada Messe (First International Dada Fair, see this article), people like Hannah Höch, Raoul Hausmann, or John Heartfield would have accepted Party in a heartbeat.