Christian Patterson’s Redheaded Peckerwood (also see the publisher’s website and my review) made it onto so many “best of 2011” lists that it was by far the most popular book last year. A body of amazing depth and sophistication, it is a shining example of what the contemporary photobook can do. There now is a second edition, and I used the occasion to talk with Christian about the book.

Jörg Colberg: How did you first hear of the story of Charles Starkweather and Caril Ann Fugate? And I’m curious about how you decided to approach the story photographically? How does one go about something like that?

Christian Patterson: Several years ago, I went to a movie theater and saw Terrance Malick’s film “Badlands.” I was taken by the film — its plot, its score, and most of all its cinematography. The film starred a very young Martin Sheen and Sissy Spacek, and they portrayed Kit and Holly, a dumb, young couple who thought they were in love. In the film, Kit kills Holly’s father, they set out on the road and he kills several other people as they try to run away. It was a crazy story; beautiful, eerie, romantic and tragic.

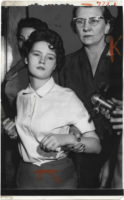

I researched the film and discovered that Malick’s script was loosely based on the true story of Charles Starkweather, a 19-year-old boy from Lincoln, Nebraska who killed his 14-year-old girlfriend Caril Ann Fugate’s mother, step-father and baby step-sister in January 1958. The couple then drove across Nebraska, and Starkweather killed seven more people before they were captured as they approached the mountains of Wyoming. I was surprised to learn about this true story that was more prolific, tragic and strange than Malick’s more romanticized film version.

I then researched the story intensely. I read every book I could get my hands on made note of anything of interest. I began with factual information — the dates, times, places and circumstances of the murders. I also made long lists of visual ideas, random words and phrases. I should mention that I posted excerpts of these lists on my website, along with various scouting photographs and outtakes from the project. I thought it would be interesting to share this information, not only as a look into my process, but as a way of inviting viewers to enter the process and decipher some of these enigmatic clues themselves. If viewers read these lists and look at the work, they will find there are connections to be made. The information can be still found here.

Digging into the archive was like falling down a rabbit hole; it opened up all possibility, in my mind. I saw how all of these different visual materials worked together to tell a story, and how they related back to what I was doing.

I made my first foray into Nebraska in January 2005, during the same time of year when the murders took place. The spree included events in and around Lincoln, and in a few small towns and roadside locations between Lincoln and Douglas, Wyoming, where the couple was eventually captured. I began by using the story as a roadmap — I traced it 500 miles west and retraced it 500 miles east. I ultimately did this five times, during five successive very cold, harsh Januaries, usually working in the field between seven and ten days each year.

In addition to working as a photographer, I had to work as a detective. I searched for traces of the past in the present — places and things of significance to the story; evidence of these events that remained out there in the world. I found things that I never imagined I would find; I even discovered personal belongings and pieces of evidence that were never recovered by the detectives who originally worked the case. All of this came as quite a surprise, and a strange thrill. But still, there was a lot of the story that no longer remained, and it became apparent that I would not be able to simply travel from the scene of one crime to another and document what was there, nearly 50 years later. The project would involve much more than simply connecting the dots; I needed to find a new way of working with this material, conceptually.

Before I finished my first trip and returned home, I visited the archives of the Lincoln Journal Star, the local newspaper that originally covered the story. There, I not only found old newspapers; I also found press releases, news alerts, original press and police photographs and courtroom sketches. I also visited the Nebraska State Historical Society, where some of the physical evidence remains in storage. There, I flipped through Caril Ann Fugate’s photo diary and the contents of one of the victim’s wallets. I also saw crime scene photographs and held the murder weapons. Encountering this material gave me chills, and I began to see how it could complement and inform my photographs.

Digging into the archive was like falling down a rabbit hole; it opened up all possibility, in my mind. I saw how all of these different visual materials worked together to tell a story, and how they related back to what I was doing. It didn’t matter that these things were produced by different sources in different formats or different times. I let go of the old way of thinking about photographic documentation, truth and representation. Suddenly it all looked fluid; everything became the archive, everything became documentation. The only thing that mattered was telling a story visually, using my research and calling on my imagination as needed. Doing this with a well-known, pre-existing true crime story was unusual, I suppose.

There seems to be a lot of hand wringing about the state of photography, about its ability or inability to depict what people like to call reality. Of course, I have no idea to what extent you had that in mind, but I’m curious about this – how did this enter your picture making, and the way you combined these images into Redheaded Peckerwood?

In order to make this work, I had to abandon traditional notions of photographic documentation, truth and representation. Photography has never been reality and it never will be. It’s a two-dimensional representation of reality, ripped off from the real world. It’s not that I’m not interested in reality, or depicting that which exists in reality; it’s just that I’m much more interested in images and ideas. As far as Redheaded Peckerwood is concerned, I think the phrase I used earlier — “after the fact” — has some additional meaning here. All photography is “after the fact.” Other people hold onto the creaky, dusty notion of photographs as some sort of reality; this only increases the potential for complexity through the many different possible readings of work that challenges or contradicts this restrictive perception of what a photograph is or what it can do. I consider this a wonderful gift to me as an artist, or any artist making work that disregards this concern with the real.

I’d like to talk about this a bit more, because I find this very fascinating. I’ve always been a bit puzzled by people’s insistence that photography presents the truth or reality. This does depend a bit on context, of course. In some contexts, photography might indeed represent a facet of reality just big enough to do the job (think of a crime-scene photograph or your passport picture). But in most contexts, a photograph tends to represent all kinds of realities, first and foremost the one the viewer wants to or prefers to see. I understand why that might have some people flustered, but if you think about it it’s such an enormous gift, because it means that photography not only can easily be the most amazing art form, photography also is easily usable: It offers itself to be used.

In your book you seem to be playing with this, by throwing together all this photographic material that, I’m sure, will confuse and maybe even annoy someone expecting the truth (or maybe it’ll be just one big puzzle). I’m curious how you approached this, because depending on how willing you were to grant some photographs the ability to show some sort of truth, while being playful with others, that would determine how you could use them as material. It must be much more fun to play with all the options available if you know how people might react, how people might be rubbed a certain way?

I think this goes back to what I said about fluidity and telling a story visually using imagination. My two primary concerns were telling a story, and doing so visually, utilizing whatever means necessary. As I made this work, I continually consulted and revised my lists of visual ideas, and I allowed my ideas to come from anywhere, as long as they related in some way to some version of the story — even if it was a version that only existed in my own head. The ideas could be based on reported facts from books, newspapers, interviews or court transcripts; from highly interpretive literary or cinematic accounts, or based purely on my own imagination, which of course was also completely interpretive.

In the early going, I held tightly to the story and strived to artfully document whatever places and things were of specific importance and relevance to the story. But there was only so much of this that could be done, and once these things were done, many narrative and visual holes remained in my personal vision for the story. This compelled me to embrace new approaches to telling my version of the story, utilizing whatever means and methods necessary. I didn’t just want to retell the story; I wanted to tell it anew.

I often say that Redheaded Peckerwood is a body of photographs, documents and objects that utilizes a true crime story as a spine. The story continually served as a source of inspiration and ideas, but what really excited me about my work was the expansion of my own artistic practice. Previous to this work, I had only worked as a photographer. And while photographs are the heart of this work, they are complemented and informed by the documents and objects that in many cases were touched by the hands of the killers and their victims. In addition, Redheaded Peckerwood employs a wide variety of photographic techniques and styles — black & white, both appropriated and original; contemporary color, forensic imagery, both real and recreated; work on location — landscapes and interiors; and staged still lifes in the studio.

As I continued my work, the story began to disintegrate, fragment and fall away. It never disappeared completely; it was always there, but its sole function was to serve as a source of raw material with which I could play. I became much more interested in the conceptual side of the work, my process and practice, which expanded beyond the documentary and into more actively interpretive, manipulative realms — appropriation, reenactment, staging, word paintings and even blasting holes in pieces of paper with a shotgun.

I suppose that I gave some consideration to how people might react; this experience pushed my buttons and pulled me in different directions, and I wanted my presentation of the work to do the same for the viewer. Making this work was a new experience for me; it brought a sense of adventure and even a sense of humor at times to the work — take for example the political limericks, the dirty jokes, or some of the titles for some of the work (“Three-Story Rat Trap,” “Shit from Shinola,” “Fruit Cake 98 Cents” and “Let’s All Go Out and Get a Steak”).

Ultimately, I wanted the work to act as a more complex, enigmatic visual crime dossier — a mixed collection of cryptic clues, random facts and fictions that the viewer had to deal with on their own, to some extent. A certain amount of mystery was essential. A little mystery goes a long way. It’s funny, because a certain amount of “unknowing” forces us to form our own interpretations and responses, to fill in the holes ourselves.

There is also a fair amount of archival material in the book. How did you go about deciding what to include, how to mix archival photographs with your own?

I should note that not everything in Redheaded Peckerwood is as it may seem — there are photographs, documents and objects that may appear to come either from the archive or from me when in fact the reverse is true. This is the exception more than the rule, but there are exceptions in all cases. And in all cases, I had a visceral reaction to the material I created, selected and ultimately included in the project.

I approached this project methodically (through my research, note taking, list making and archival digging) but responded to its ongoing development intuitively (through my own image making and continual editing, sequencing and refining of all the material). I kept a mental inventory of my research, my lists, what I found in the archive, and what I was shooting. This was a fairly obsessive, ongoing process, including periods of inactivity, lasting five years. I treated every photograph, document and object as another piece of the puzzle. I wanted everything to work together; I wanted to confuse what was old and what was new, what was archival and what was not, what was authentic to the story or perceived as “real” versus what was simply a beautiful, eerie, sinister or strange image.

There are things about my nature as a person and photographer that relate well to the nature of Redheaded Peckerwood. I often strive to make timeless, or perhaps more appropriately, time-neutral images — images that bear little or no signifying evidence of the time in which they were made. Most of the images in Redheaded Peckerwood are successful in this respect, with a few exceptions. And as the work deals with a story from another time, this seemed necessary. I also feel I’ve always had a certain “forensic” way of seeing. I take pleasure in looking at things in a very intense, concentrated way — a very photographic compulsion. I say all this because I think these traits helped me to establish a fairly consistent aesthetic and feel throughout the book, despite the mix of material. Take for example the color palette — it’s fairly consistent throughout the entire work — the work has its own yellow, its own green.

There is a second edition of your book now (congratulations!), and I saw that you mentioned there would be “Noticeable enhancements. New visual content.” Could you talk about this a little bit?

I’m fortunate to have had the opportunity to print a second edition of the book, for a number of reasons. First, I wanted the book to continue to be available. I have nothing against the first edition of the book being a collected or valued object, but I don’t want that to be a barrier to those who wish to access the work. I made the work to share it, not to have it become this unseable thing. Second, I wanted to make a few subtle changes and refinements to the book. And ultimately, when we went on press, we had the opportunity to work on an amazing new printer that made this new printing even stronger than the first.

The cover of the second edition will be subtly darker. I like the idea of the cover image changing with time.

Most significantly, we printed the second edition on a new ten-drum Heidelberg press using a new black ink and a light gloss varnish instead of the matte varnish we used on the first book. I also supplied improved files for a few of the images. I couldn’t believe the difference we were seeing with the new printer, ink and varnish. I’m sure all of these changes will be apparent, especially to anyone comparing the two editions.

Lastly, I revisited the material I acquired from various archives and added some images to the booklet insert, and so now the essays are accompanied by this new visual content.

Again, most of the content- and visual-related changes are subtle, so in that sense the book hasn’t changed all that much. But I’m excited about the improvement in the quality of the printing, which was already quite good, and the opportunity to add a few new touches, like the altered cover and additional images.

In his essay, Luc Sante calls the book “a kind of subjective documentary photography of the historical past.” I’d be interested in your thoughts about that term.

I’ve always felt conflicted about text in photography books. I very rarely read texts or essays; I prefer to have a direct, unmediated visual experience with the work. At the same time, I understand that text can provide context, among other things, and that it can add something to the experience of the work for some people. But with Redheaded Peckerwood, it was extremely important to me that a certain amount of mystery permeated the work and that any text did not detract from that mystery. Certain information could never be discussed or revealed. I’m very fortunate to have had two great essays written for the book. Luc Sante’s essay provides a historical/social context and Karen Irvine’s essay provides an art/conceptual context for the work. Each essay provides and reveals some additional information, but not too much.

I think it’s important to quote the entire sentence that Luc wrote: “In Redheaded Peckerwood Christian Patterson is working out something that hasn’t been done much before, if ever: a kind of subjective documentary photography of the historical past.” Further, he goes on to say that Redheaded Peckerwood “walks the fine line between fiction and nonfiction.” I think that Luc is referring to the creative license I took with this well-documented pre-existing story that has been the source of inspiration for numerous books, films and movies over the past 50 years. But I think my handling of this material is dramatically different from anything else that’s been done before, and that to me is part of what makes it worthwhile.

I’d also like to direct you to Karen Irvine’s essay, which goes some way in explaining exactly that to which Luc is referring. She explains things much better than I ever could:

“Patterson approaches the archive as a space of negotiation, not authority. Patterson revisits and repackages the past, destabilizing the archive and making it a place of activation and possibility. Through his deft blending of fact, popular cultural elements, and personal vision he seems to be asking, ‘What are the limitations of the archive? What might it conceal?’ Hal Foster has written about artists who mine the archive: ‘the fact that … artists turn the archive from an “excavation site” into a “construction site,” is welcome … it suggests a shift away from a melancholic culture that views the historical as little more than the traumatic.’ In Patterson’s work, the archive is exposed as being incomplete and improvisatory, and this makes way for the implicit, liberating acceptance that human nature is unpredictable and flawed, not only in a tragic way, but in a strange and almost comic one as well. As Fyodor Dostoevsky, author of Crime and Punishment, reportedly once said, ‘Nothing is easier than to denounce the evildoer; nothing is more difficult than to understand him.'”

“Redheaded Peckerwood is not an artifact of cultural memory. It is an interpretation of history that operates like memory and gives the past life in the present. Patterson mines the archive and injects the past with possibility, making art that is at once both contemporaneous and historical. His refusal to delineate what is real and what is fiction prevents us from mentally shelving the events as part of history. Forget considering them only in a passive, distanced way. We must actively engage with our imaginations and our memories, and in that hazy interior realm where they intersect.”

I suppose we could discuss archives now. Assume you had a complete archive of something — this could be out of a Borges story — would you then have the full story? But what I’m after is something else. I’m more interested in your own role here, your role as the artist, your role as someone who creates what looks and feels like a documentary body of work, but isn’t at the same time. I love the fact that the book is both. As much as I hate using analogies from the natural sciences, the example of a photon, say, being both a wave and a particle at the same time as long as it’s unobserved as either seems relevant here. After all, all documentary work always involves a lot of fiction (history itself is a perfect example: a grandiose piece of fiction, composed entirely of facts), but we don’t want to see it that way. In much the same way, “art photography” is supposed to be fiction only, and of course it often is. But books like Redheaded Peckerwood are more like a photon: It’s both, a documentary (in the strictest sense of the word) and a piece of fiction (again in the strictest sense of the word) — and only when you “observe” it does it fall into one category or the other (it can’t stay in both). That’s where I have a slight problem with what Karen Irvine writes when she talks of “an interpretation of history that operates like memory and gives the past life in the present” – history in the sense of written or compiled history is an interpretation, just like your book is an interpretation of sorts.

Of course, there is a difference between that which historians do and that which you do: Historians are interested only in facts, even though, of course, what they produce is a construct that future historians might just brush aside, for whatever reason (new facts often play less a role than a changed cultural climate). What you do, however, is to do a historian’s job, except you are willing to do it in an artistic way, working with the limitations and possibilities of your medium, while still telling a story. The reason why this interests me so much is because I think it opens up opportunities to engage with the world, opportunities to realize that the word “truth” can have different kinds of meanings, many of them if not being the same then at least equivalent. For writers, we have long accepted this. A nonfiction book and a fiction book about something historical can each tell more or less the same story — and we know how to understand and treat the differences. As Karen Irvine wrote in the case of a novel “we must actively engage with our imaginations and our memories.” But for photography, we haven’t made that step, yet. We’re still stuck with people’s ideas that photography presents the truth or something real or whatever. I’m tempted to think a book like Redheaded Peckerwood is a perfect example of what can be gained by finally leaving this simplistic approach to photography. It is a true story, and at the same time it is the story you decided to tell (if I did it it would look very different).

What do you think?

I’m not familiar with Borges or his work, but I did find this rather insightful quote from his biographer Edwin Williamson: “His basic contention was that fiction did not depend on the illusion of reality; what mattered ultimately was an author’s ability to generate ‘poetic faith’ in his reader.” This, to me, is a beautiful, perfect encapsulation of the way that photography works.

Another “Borgesian” quality is narrative non-linearity. When I first began making this work, I held tightly to the chronological narrative of the story. But as I continued to make work, explore and appropriate the archive, and edit, sequence and refine the material, I also began to freely mix the material. My interests and motivations for doing this were were two-fold. First, I had a visual interest. With photography, the visual element greatly increases the interpretive potential and therefore unavoidably complicates the narrative. Second, I wanted to push the work and its interpretation in unexpected directions. As Williamson said, I had to generate poetic faith in the reader.

I agree with what Karen Irvine wrote about “history that operates like memory,” and I think it agrees with what you said about interpretation, if we acknowledge that memory is largely biased, completely selective and therefore highly interpretive. I’m not sure how to respond to or improve upon everything that you’ve just said — the issues of truth and representation are a problem in photography for many people. But when it comes to most of the photography that I look at or make myself, I’m really most concerned with what lies within — our feeling and imagination.