There is a photograph of Georg August Zenker in the book whose title bears his last name. On page 26, a “[f]ramed photograph from the lounge room of the Bipindihof” (the caption tells us) shows someone who looks very German staring back at us. There’s a slightly bemused look on his face. Change out his clothes for something very slightly more modern, trim off the beard, add some of those pretend-stylish glasses that middle-aged German men wear, and you might be peeking into the face of one of those men that you ordinarily would expect to see in some mid-level manager position at a provincial savings bank, but that have come to dominate contemporary German politics: sub-mediocre technocrats. The conservative party’s candidate for the chancellorship, Armin Laschet, state premier of North Rhine-Westphalia, exemplifies this type of man perfectly, with his complete lack of even an awareness that ambition might cover more than the next rung of power and his willingness to give more to those who already have a lot, while keeping all the others down. You wouldn’t want to give these men more power than over an upcoming promotion of low-interest home financing. But now they have to deal (or rather pretend to deal) with climate change or a pandemic. It’s altogether not very surprising that the outcome is a mess (where the next corruption scandal is merely one news cycle away).

Nowadays, these German men deal with their own — unless they somehow feel compelled to decree that “the safety of the Federal Republic of Germany is being defended at the Hindu Kush” (actual quote, translated by me, by the Zenkerite who was defense secretary in 2002). Back at the end of the 19th Century, that safety was being defended in places such as Kamerun, one of the small number of colonies Wilhelminian Germany had acquired. Obviously, Germany’s safety wasn’t going to be defended any more in Afghanistan than in the area that now is mostly part of the modern-day Republic of Cameroon. Instead, German administrators and soldiers were defending their country’s rights to do as it pleased. This, of course, was couched in the name of some greater good that, alas, for the most part eluded those who were at the receiving end of said defense. So it goes, to use Kurt Vonnegut’s phrase.

Imperial Germany had wanted a seat at the table of colonial powers, joining the likes of Great Britain and France, and briefly got it. During World War I, Germany lost all of its colonies (that it was unable to defend). But foreshadowing how the first half of the 20th Century would evolve, they still managed to stage its first genocide in what is now Namibia. Of course, contemporary Germany would rather not have a seat of the table of former colonial powers. But if you re-erect the country’s former imperial palace in the capitol and then move the collection of the Ethnological Museum into it, which is filled with looted artifacts, then they were basically asking for it (not that they would have had a choice anyway). Consequently, a discussion over all of this has broken out in Germany, a discussion that, of course, the savings-bank directors in power would rather not have. (So it goes. — KV)

Georg August Zenker was a botanist and gardener whose career resulted in a position at the farthest inland outpost in the German colony of Kamerun. There are somewhat conflicting accounts of his activities in the area. He was dismissed from his post, yet he returned as a private citizen, and he died and was buried there. There was talk of improper behaviour as a colonial administrator, some of which in retrospect is hard to prove. What is not, however, is the fact that he fathered a number of children with a few women, only one of whom was his wife. Whatever the truth might have been, there exist dozens of descendants who wear his name and who today either live in Cameroon, in Germany, or elsewhere. Portraits of a quite a few of them can be found in the book. In addition, there are longer interviews with three Zenkers, all of whom proudly recall the history of the family and the many achievements of their (great) grandfather.

The very first facts a viewer learns about Zenker come from the man himself, though a selection of letters that he sent back to Germany. The letters are filled with details from different parts of his life. There are short descriptions of daily life. There are numerous descriptions of his process of killing animals and sending them back to Germany, to be used in museums. And there are reflections of the ubiquitous racism and the casual colonial violence that men like Zenker probably didn’t think much of. To what extent the latter connect with reasons given for his dismissal isn’t clear. It might not matter anyway, given that the view Germans had of the country they ruled for the most part stands outside of what we consider civilized discourse today. Where facts or accounts might differ from one administrator to the next, the underlying language is one of casual, yet brutal racism, in which the life of a person who is not white doesn’t matter all that much. To pretend that this was not the case is little more than window dressing.

At the end of the book, there is a long list of specimen prepared by Zenker that are in the possessions of museums in Berlin, the Ethnological one — in the news for the Benin Bronzes it holds — among them. The list is quite extensive, and it sickens me to consider the slaughter of all the animals just so they could be prepared and then sent off to Germany. But its length also serves as a reminder to what extent colonial violence was an important pillar of Europe’s humanities and knowledge industry (lest we forget, photography is part of that).

For the most part, the book focuses on the very location of Zenker’s activities, the village where he built what his descendants refer to as the palais, a massive building that in German probably would be described as a Gutshof (manor) and that is named Bipindihof (Bipindi is the name of the locale, and a Hof in German is a farm of sorts). Given it was built with stones, it has not (yet) fallen into complete disrepair, even though it clear has seen better days. Members of the family are still attempting to take care of it, with neither the Cameroonian government nor the German one (through its embassy there) being very interested in maintaining it. Around the manson, there appear to have been farm-related activities, most of which have been stopped (one of the descendants talks of the government shutting things down in part by building a pipeline through the area).

The artists behind the book, Yana Wernicke and Jonas Feige, conclude their book with a relatively large number of questions, including for example “What entitles us, of all people, to explore the Zenker story?” or “How to reconcile the image of a man who could both despise people because of their skin colour, yet dearly love his own children whose mother was a black woman?” In the end, they conclude, that “we have just as many, if not more, questions today than when we first embarked on this journey.” A few years ago, when I was still a lot more impetuous, I would have thought that this conclusion is merely a cop out: after all, there always are more answers, aren’t there?

But now I know that the presence of more answers merely points at the fact that our lived reality, combined with all the baggage we inherit, prevents us from arriving at simple solutions most of the time (which is one of the reasons why I’m finding social media more and more toxic). An answer provides a solution, a way to end a story, a way to move on. Moving on is good, of course, because it feels good. But the reality is that history does not allow for a moving on most of the time. Whatever solution might exist is less an answer and more an attempt to do justice where actual justice cannot be fully had any longer. The descendants of those who were responsible for gruesome violence in the past (and this obviously includes me as a German citizen) will have to live with their lifelong responsibility to deal with what can never be resolved. For those interested in how one can understand and deal with this, Michael Rothberg‘s The Implicated Subject is a good start.

As implicated subjects, Yana Wernicke and Jonas Feige have done a great job diving into just a small aspect of Germany’s much ignored colonial history, a topic that despite efforts by conservatives to bury it is likely to remain with us for decades to come.

Recommended.

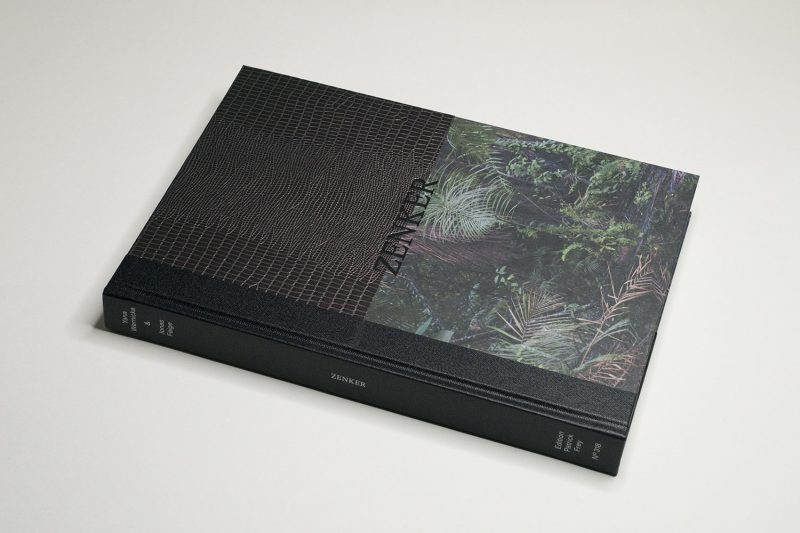

Zenker; photographs by Yana Wernicke and Jonas Feige; texts by a number of authors (German/English); 268 pages; Edition Patrick Frey; 2021

Rating: Photography 4.0, Book Concept 4.0, Edit 4.0, Production 5.0 – Overall 4.3

Ratings explained here.