In a conversation with Matthias Flügge that is part of World Wide Order, Julian Röder focuses in on his approach to photography by setting himself apart from widely held beliefs. It’s a statement worthwhile to be quoted in full:

“I don’t subscribe to the kind of dogma propagated by Robert Capa – the claim that you have to be as close as possible to what you are photographing to make good images. You don’t have to shadow some disadvantaged group or track a precarious situation just because you think that you will be able to say more that way. I think this is misguided, because as a photographer you are not one of these people or part of their situation, and you can hardly convey the conditions and contingencies of their lives. Certainly, you can depict the symptoms of a problem, but not its origins and not your own position of looking in from the outside.” (p. 104)

In principle, there is a lot to unpack in the statement, which, one can be sure, a lot of photographers will not agree with at all. That aside, especially in this day and age of click bait and of the constant need for some daily visual drama, to be looked at and shocked by today and then forgotten tomorrow, Röder’s approach puts him at a serious disadvantage.

But photography, especially of the non-electronic form, has a life span that is larger than any of the “Pictures of the Day” galleries. And it is exactly the photography made consciously with such an approach in mind – Röder’s rejection of the Capaesque drama – that can at least supplement our daily diet, if not hint at those of the medium’s possibilities that are so ill-served by the internet.

Our approach to and consumption of photographs of course mirrors the societal and cultural modes of living and working we have come to accept. Over the past decade, their extremes have dominated the news, in the form of a vague, self-perpetuating, and never-ending “war on terror,” of short-lived bursts of protests against the dominant economical order, of stock-market crashes and economical crises… This is, in effect, the World Wide Order that Röder has been photographing. This is what constitutes the basis for the seemingly so different bodies of work assembled in the eponymous book.

Of these photographs, Röder’s depictions of the economic summit protests might be most widely known. What do these photographs have to do with images from arms or trade fairs, with images of borders? Well, everything – at least that is the point made very forcefully in World Wide Order. So while at first glance the book might look like a catalogue raisonee of sorts, it isn’t one. Its aim is to tie together various aspects of a system that, it is being argued, doesn’t serve us any longer (or maybe the vast majority of us – some people are doing quite well, thank you).

World Wide Order is an ambitious and deeply political book, using photographs that at least according to the visual mores of our times appear to be anything but. In the summit pictures, the photographer adopts a Gurski-esque approach, offering sweeping vistas where whatever drama was to be had seemingly is contained by the apparent grandiosity of the scene itself. In the trade and arms fair pictures, in contrast, that approach is changed to a form of documentation that gets closer, but that, at the same time, removes all signifiers (signs, names, …). Thus the drama put on view is not necessarily a visual one. Instead, it is a structural one, one whose manifestations are depicted in photographs.

The actual work of tying things together has to be done by the viewer. Or rather, the work is tied together quite strongly, but the viewer’s mind has to come to the realization that and how they are connected in ways that extend far out from what is being photographed. It’s an ambitious, extremely well-produced book, with a lot of work that deserves to be seen more widely (especially since it doesn’t look as if the problem is going to disappear any time soon).

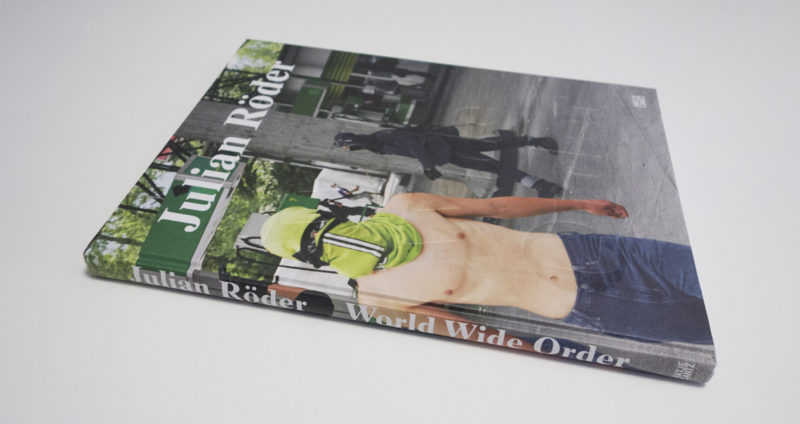

World Wide Order; photographs by Julian Röder; essays/interviews by Matthias Flügge, Elisabeth Giers, Sean O’Toole, Kolja Reichert; 132 pages; Hatje Cantz; 2014

Rating: Photography 4, Book Concept 4, Edit 3, Production 5 – Overall 4.1

Ratings explained here.