When the German writer Walter Kempowski‘s first massive collection of war-time writing entitled Echolot (Sonar) was published, I couldn’t wait to read it. It centered on a few months around the battle for Stalingrad and the collapse of Nazi Germany’s 6th Army. Finally, I thought, I would be able to understand what Germans had been thinking during the Nazi era. I remember how bewildered I was reading these letters, diary entries, and other records that had been written by a collection of mostly ordinary people. Almost none of these people had anything other than the daily minutiae of their lives in mind, a large collection of what I thought were petty, irrelevant things.

It took me a while to understand that the experience of war cannot be fully communicated. Aspects of it can. But even those register differently for those who actually experienced them and those who merely read about or view them. And I’ve learned that there actually are quite a few seemingly irrelevant details that in actuality can define the difference between life and death. Take for example the patterns of tape that Ukrainians place on their windows that even when the glass shatters from an explosion will prevent it from becoming a set of dangerous projectiles.

It is one thing to make such observations from afar. It’s very much another to live in a country that is under attack. Following its playbook from Syria (where the West stayed quiet about the atrocious war crimes committed), russia has been bombing Ukraine in an indiscriminate fashion, targeting hospitals, air-raid shelters, cultural institutions, religious buildings (this past weekend, Odesa’s Transfiguration Cathedral was attacked with a missile), restaurants, and of course apartment buildings. Occupying russian forces have tortured and murdered civilians willy nilly (this article is worth your time). Furthermore, thousands of Ukrainian children have been kidnapped to russia.

At the very beginning of the war, Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy released a short selfie video that showed him and a few members of his cabinet standing in Kyiv at night. “We are all here,” he said, dispelling notions that he would leave the country for a safer location. In the days that followed, millions of Ukrainians did leave their country, seeking refuge all over Europe. Many of them are still stranded abroad. But for many others, the option to leave did not exist; or they decided not to exercise it. Men, of course, were not allowed to leave.

Those who stayed behind have to live life under war conditions, which entails a number of challenges too difficult to imagine for those who have never experienced them. I personally grew up hearing air-raid sirens regularly; but this was every Sunday at noon when they were tested. I never got used to the sound, but I also knew that there were no actual consequences. There would be no explosions. What might it be like to have the real experience instead? I don’t know. I’m unable to imagine.

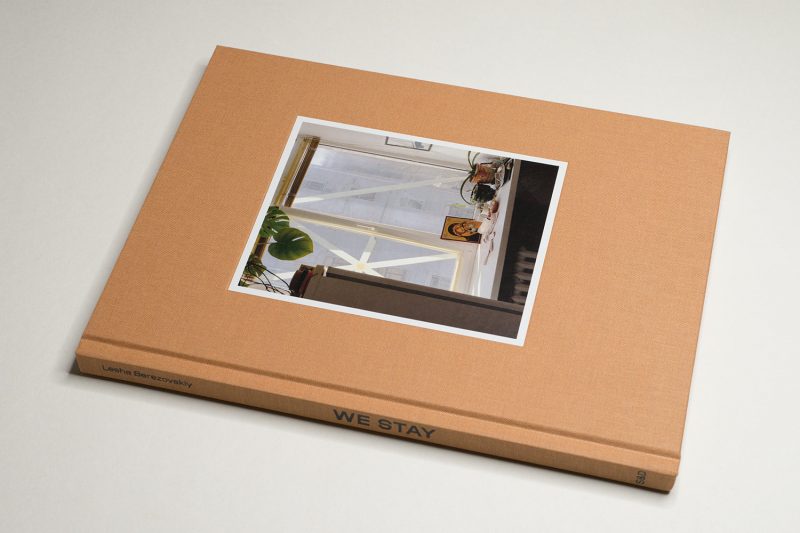

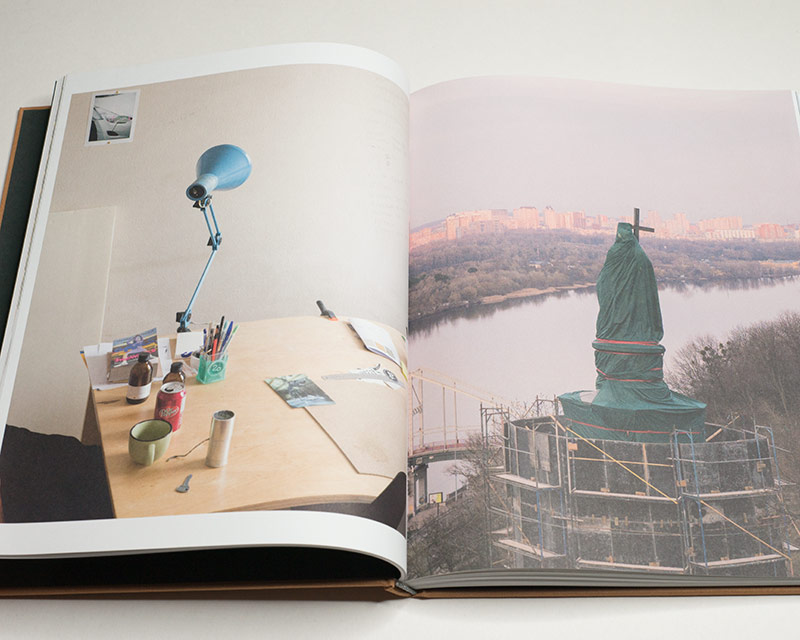

With We Stay by Lesha Berezovskiy, there now is what I think is the first photobook chronicling the earliest days of war from the perspective of people living in the war zone (if there are other books I am not aware of them). The book shows the photographer, his wife Agata, and a number of friends (plus some strangers) living their lives during the first 13 months of the war. Some of the locations known to those following the war from abroad make an appearance, such as the liberated suburbs of Kyiv and the bridges the Ukrainian army had blown up to protect the country’s capital.

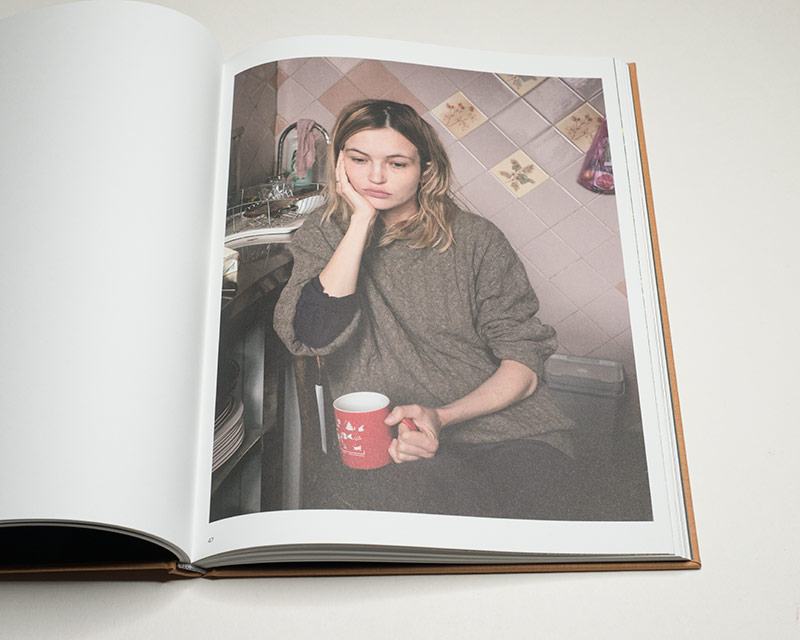

But mostly, the book delivers the experience I first encountered with Kempowski’s book. If as a viewer, you’re only familiar with the news imagery coming from Ukraine, the book might confuse you at first. This is a good confusion, though. After all, photographs are not the best tools to communicate feelings and thoughts. We Stay solves this problem by adding short snippets of text to some of the photographs in the back. These read like diary entries, but they could have also been written after the fact. Either way, they strongly communicate the inner world of the photographer and his friends.

I should note that the text is available in English and in German. There’s a translator listed in the back, but it’s not clear which text actually is the translation (maybe the original was written in Ukrainian and not included?). I’m bringing this up because for some of the snippets, there is a noticeable difference between the English and German text, with the German text including parts that are not present in the English version.

The inclusion of the many portraits and of the text is crucial for the book. This in fact has been one of my recent misgivings about so much of contemporary photography. There’s nothing wrong with a collection of pictures without people. But if you want to communicate a human experience, unpeopled pictures can only do so much.

Furthermore, the book also deftly sets photographs taken outside against Tilmannsian interiors. As already noted, some of the former depict scenes that in the early days of the war made it into the news. These pictures become re-charged through their placement in the vicinity of found still lifes from the comfort of the photographer’s home.

The combined effect points to one of the main reasons why the photobook is such a powerful vehicle for visual communication. The sum of its photographs can become vastly more than the collection of its individual members simply because the pictures manage to create an added charge in each other.

Taken together, We Stay is a book that deserves to be seen widely, in particular in those parts of Europe that still live under the illusion that things on the continent will go back to normal or that enjoy the comfort of their own safety without wanting to do too much for Ukraine (it’s a Swiss publisher…).

Recommended.

(Please note that this article follows the convention used in the book for the spelling of the aggressor country.)

We Stay; photographs and text by Lesha Berezovskiy; 136 pages; Sturm & Drang; 2023

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing to my Patreon. There, you will find exclusive articles, videos, and audio guides about the world of the photobook and more. For those curious, there now is the possibility of a trial membership for seven days.

Much like journalism, photography criticism involves a huge investment of time and resources. When you become a subscriber, you not only get access to more of my work. You will also help me produce it (including the free content on this site).

Thank you for your support!