Unlike in the West, in Japan what we call paganism has survived into the present day in the form of its Shinto religion. But also manifested through, let’s say, yōkai. Consequently, the natural world isn’t seen only as a passive canvas that can be dealt with willy-nilly. At the same time, the Japanese landscape has been subjected to a large amount of modifications, which usually are incredibly stylized (even where they are merely concrete barriers set around rivers).

“Universal principles make up nature,” Donald Richie wrote in Japan: A Description, “but nature does not reveal these principles, in Japan, until one has observed nature by shaping it oneself. The garden is not natural until everything in it has been shifted. And flowers are not natural either until so arranged to be. God, man, earth—these are the traditional strata in the flower arrangement, but it is man that is operative, acting as the medium through which earth and heaven meet.”

A little further down he continued: “A garden is not a wilderness. It is only the romantics who find wildness beautiful, and the Japanese are too pragmatic to be romantic. At the same time, a garden is not a geometrical abstraction. It is only the classicists who would find that attractive, and the Japanese are too much creatures of their feelings to be so cerebrally classic. Rather, then, a garden is created to reveal nature. Raw nature is simply never there.” (You can find the essay in A Lateral View: Essays on Culture and Style in Contemporary Japan.)

This reveals a very different sensibility towards both the natural world and the constructed environment than the one we know in the West. With this in mind, you can probably see how a disaster such as the meltdowns at the Fukushima Daiichi power plant after the 2011 tsunami created a stunning catastrophe.

This statement would be true for any country (on second thought, I’m not so sure any longer the statement applies in the US, given the sheer indifference displayed by large parts of the population towards both the pandemic and the enormous wildfires in the West). But a country with such a specific relationship between the natural and man-made world could only have been shaken up by the fact that there is one more addition to the various invisible forces that guide the world: radioactive material whose presence potentially creates a huge hazard for anything and anyone exposed to it.

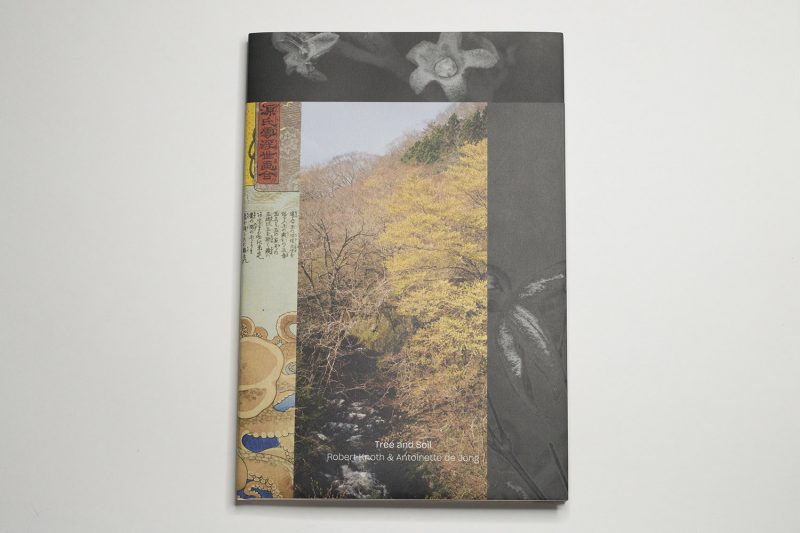

This is the background of Antoinette de Jong and Robert Knoth‘s Tree and Soil, a book that combines photographs from around the closed-off areas near the Fukushima plant with images of a collection gathered by Philipp Franz von Siebold, an explorer who collected material in Japan (this is now housed at the Naturalis Biodiversity Center in Leiden, the Netherlands).

If you’re expecting to see a lot of photographs of abandoned buildings in empty towns, you’re going to be disappointed by the book. There are some of these pictures. But the majority of photographs taken in Japan focus on the land itself, on forests, streams, boulders — all those entities that in the country’s traditional thinking habour a spirit.

That said, one of the most arresting photographs is of an abandoned building. Not quite halfway into the book, one of the many gatefolds open to show a row of five vending machines that are housed under a protective roof (much like what you see at gas stations, with the vending machines replacing gas pumps). Its English language signage indicates the presence of a “drink paradise” (the Japanese text, Google Translate tells me, is more prosaic, saying it’s a liquor store). Curiously, two of the machines are still fully lit, which has me believe one could still get a drink.

The area around the stricken power plant was evacuated in haste. But somehow, even years later, nobody thought of cutting the power to those vending machines. In the larger scheme of things, it’s an irrelevant detail. It’s the details and their seeming irrelevance that gives art true meaning: after all, in a strictly neoliberal sense, the people who had to leave these towns ought to just rebuild their lives elsewhere. But such thinking only dispenses with what makes life truly meaningful and displaces it with a culture so shallow that it were an affront to even remotely consider the word “depth” in its description.

With its photographs of forests and of specimen and drawings created by Von Siebold, its reproductions of traditional Japanese art and of scientific studies, and its occasional giving voice to humans, Tree and Soil evades descriptiveness, instead embracing an atmosphere. It asks of the viewer to think about their engagement with the natural world: when you leave your house, do you register the chipmunk’s warning signals that sound as if it were a bird? Could you tell the difference between the cardinal’s babies’ cries for food from its parent’s chirping? Or do you simply go on, get in your car, and drive away?

The book was made with the typical attention to detail that we’ve come to know from photobook making in Holland. The dust jacket can be taken off and unfolded, to reveal a double-sided poster of sorts. There are ample gatefolds whose function and necessity, however, isn’t all that clear to me: what is revealed isn’t any different than what’s already visible elsewhere (with the exception of those vending machines). Occasionally, pictures will wrap around pages (which for sure is going to rankle traditionalists).

Thus, Tree and Soil becomes its own precious object, and its preciousness only serves to enhance its overall message. You’ll have to go through the book many times. I suspect that each time, something else will have to be discovered. It is through the reproductions of scientific reports that the topic of radioactivity is being brought up. While it’s difficult to imagine how else one would go about it, that type of description almost isn’t needed. Throughout the book, it’s easy to pick up on the idea of something having gone awry.

But then, don’t Von Siebold’s specimen and beautiful drawings connect with those scientific reports? Isn’t the thinking behind them essentially the same? Couldn’t there be a straight line drawn from the Western explorer’s colonial idea of Japan as a country that needed to be deciphered, sliced and diced to the disaster caused by the consequences of the very same thinking, namely that nature’s sole purpose is to be exploited?

Turns out that radioactive materials aren’t easy to control. When they’re out of control, their terrible power will make any yōkai monster seem tame in comparison. Actually, the Japanese already have a monster created from radioactivity even though it’s not thought of as yōkai: Gojira.

What exactly will it take for us to finally take care of our natural environment? I’m writing this article as there are huge fires in the (US) American West, that clearly are one of the many consequences of global warning. Billions of years into the future, before it dies our sun will expand massively and scorch the surface of this planet, making life impossible. It’s as if our plan was to do the very same ourselves, just a lot earlier. What’s wrong with us?

The book’s colophon tells me that it’s the “[f]irst and only edition.” The publisher’s website speaks of a “unique edition of 925 copies, of which 400 copies are for sale.” If you want a copy of the book, you might have to move fast.

Tree and Soil; photographs by Antoinette de Jong and Robert Knoth; essay by Erik de Jong; 112 pages with 10 gatefolds; Hartmann Books; 2020

Rating: Photography 3.5, Book Concept 4.0, Edit 3.0, Production 5.0 – Overall 4.0

Ratings explained here.