I can’t say that I’m an expert in the area that Timothy Snyder described in his book Bloodlands. What I know I know from the book. If you look through the Wikipedia page, towards the bottom, the reception of the book is discussed. Some of Snyder’s points were highly contested, and part of the protest appeared to have included accusations of bias towards some of the states that occupy the region.

The latter would in part be only logical, at least as far as I understand it, given that what we see as clear-cut borders on our contemporary maps do in fact not neatly separate people quite as clearly as we might be tempted to think. Before the borders in Central and Eastern Europe were re-drawn, many of the countries in the area had sizeable minorities, with often rich local cultures that often intermingled.

Even as after World War 2 large numbers of people were literally made to move, a process that was violent and that destroyed the livelihoods of many, many people, physically moving people will not eradicate cultures, connections, and conflicts that had been established over the course of centuries. It will also not eradicate memories of oppression and mass murder at the hands of those who committed them, Germany and Russia.

As far as I understand it, there is a strong sense of solidarity between the countries that now occupy the area Snyder covered in his book. At the time of this writing, this solidarity manifests itself very strongly in the support Ukraine receives from countries such as Poland or the Baltic Republics. I don’t think in the West, people understand the reasons for that support. Even the word solidarity seems not strong enough. There is a shared history that includes culture just as much as being violently oppressed.

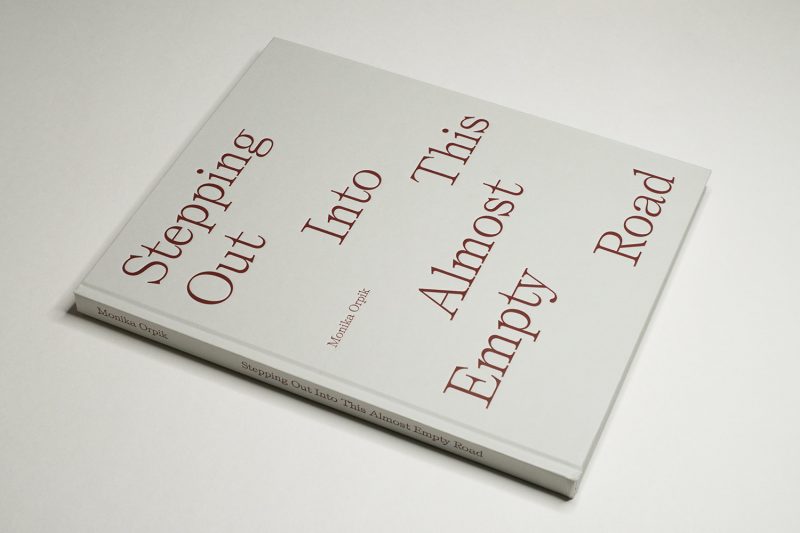

As far as I can tell, the above forms the basis for Monika Orpik‘s Stepping Out Into This Almost Empty Road. I’m not trying to be coy here with my use of “as far as I can tell”. It’s very much possible that, say, Polish viewers and readers will find much easier access to the book than I did (I would have to ask people). And the book does include a number of clues what it tries to center on. But they are very difficult to find for someone who is not familiar with the location.

Let’s back up a bit. In a nutshell, the book contains a large number of photographs in a very bucolic setting. There are hints here and there that the location is somewhere in Eastern Europe: there are the occasional post-Soviet markers such as interiors of buildings, Christian-Orthodox crosses (that possibly are more widely known beyond the area now, given that so many of them are in the news from grave sites in Ukraine), or a group of priests.

I quite enjoy the overall mood that is established by these photographs. I get a feeling of a hinterland, a place that somehow has been left behind a bit. It’s not a neoliberal look at it, pointing a finger at what’s lacking, though. It’s simply observant of the land and its natural beauty.

There are three large blocks of text in English and a language that uses a Cyrillic alphabet (it’s not Russian, given that there are a few characters used that don’t exist in Russian). You’ll have to read both texts to figure out that the country in question is Belarus. The text conveys the voices of people from there talking about their experiences with the violent dictatorship in their home country. There also are four grids of similar images plus a short sequence of dark photographs of a pair of hands. What these are intended to communicate I don’t understand.

I think that one of the biggest challenges for any photographer when making a book is to realize that their audience often does not know everything you want to tell them, yet. The photobook is this curious thing where you have to slowly build up what you’re trying to get at; someone who only knows the pictures — and nothing else — will have to be able to figure it out. The inclusion of text does not change this challenge radically (unless you use text that explains what you’re after, in which case the whole thing becomes something entirely different).

Looking through Stepping Out Into This Almost Empty Road and thinking about what I started this article with had me think that I might simply not be a member of the book’s target audience. Maybe its target audience is exclusively located in Eastern Central Europe. My sense is that the book’s makers took a lot of information for granted, information that I simply have no access to.

And the book does make it very hard to figure out what’s going on. I wouldn’t want to claim that it’s trying to be mysterious on purpose (I wouldn’t know, and in any case, it would be unfair to make this claim). But I will say that a Western audience, in fact any audience really that’s not familiar with the region and its culture and politics, will find it difficult to access the book and to find the intended meaning beyond the landscapes.

For example, outsiders are unlikely to know what OMON is (it’s the vicious riot police you see in Belarus and Russia). If you use a specific term like this in a book (you find it in the first text), you want to include a note for an audience not familiar with it. I know that this seems like a small detail, but it’s one out of many in the book.

In general, in your photobook, you want to avoid two extremes: giving too much information and giving too little. If you give too much information, access to the book will be sharply reduced to something prefabricated. If you give too little information, people are simply not going to understand what you’re trying to get at.

In the latter case, the general sentiment that I often hear about this falls along the lines of “I want this to be mysterious”. Being mysterious is good — if a sense of mystery is the overall idea. But an audience will still have to understand that. This might be the hardest aspect of photobook making.

That said, obviously not every book needs to be made for an audience outside of the region where it was photographed. I suspect that the book will resonate with people in the area. At the same time, especially in light of many Westerners being indifferent about Russia’s genocidal war in Ukraine (just one of the many aspects of the region that’s not understood well — if at all), it’s exactly Western audiences that would benefit most from learning more about the region.

Stepping Out Into This Almost Empty Road; photographs and transcribed interviews by Monika Orpik; 124 pages; Ośrodek Postaw Twórczych (OPT); 2022

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing to my Patreon. There, you will find exclusive articles, videos, and audio guides about the world of the photobook and more.

Much like journalism, photography criticism involves a huge investment of time and resources. When you become a subscriber, you not only get access to more of my work. You will also help me produce it (including the free content on this site).

Thank you for your support!