I imagine that raising teenage boys is difficult — especially these days. Masculinity and its ubiquitous toxic outgrowths rightfully have become a focus point as all those affected by their many consequences have started to raise their voices. As a consequence, there has been a slow re-alignment of the roles and responsibilities of all members of society, with straight cis men being forced to re-evaluate their responsibilities.

I see the rise of neofascism all over the world as a direct consequence of both neoliberalism, with its direct appeal to sheer power and “might makes right”, and of that backlash against unfettered masculinity (whose two main pillars are misogyny and violence).

However ridiculous many of the leaders of neofascists parties look and act, their open support of a (partly imaginary) older order, in which “boys will be boys” and everybody steps back to their place in the back, has deep appeal to large swatches of people (in her new book, Natascha Strobl calls these parties “radicalized conservatives”, and she outlines the way they operate — I hope the book will find an English translation).

You can understand Great Britain’s Brexit slogan “take back control” as an open expression of a struggle over masculinity. England’s ruling class largely consists of a group of people who grew up leading very sheltered and privileged lives and who experienced masculinity mostly as a simulation of what all those other men do who don’t grow up being rich. It is the latter who feel wronged by a changed world, while the former have now found a way to finally experience some form of masculinity.

Whenever I see a picture of, let’s say, Nigel Farage attempting to convey the spirit of “take back control” I see a man who has no understanding of his own masculinity whatsoever and who panders to what he thinks it might mean. This is cartoonish and sad, but people don’t respond to visuals. Instead, they respond to a man airing their shared grievances.

It’s the same mechanism playing out when, say, Donald Trump climbs into the cabin of a truck and for some short moment acts out what he imagines the corresponding masculinity might be. The fact that these people would not drink beer or get into a truck when they’re not acting for the public is largely irrelevant because it misses the real point: however privileged they might be, neofascist politicians feel connected to the grievance they exploit. Resentment is a hell of a drug, especially when it plays out over masculinity.

I imagine that this situation creates a terrible conundrum for parents, especially fathers: how do you raise your teenage boys in such a way that they become decent people, possibly avoiding the shit that you’ve done in your own past, while larger parts of the outside world present the exact opposite of that as the go-to model, where, for example, thoughtfulness and care for others often is derided as “being woke”?

And then if you’re a teenage boy, how would you respond to all of that? I’m not a father, so I don’t have access to this type of perspective. But I was a teenage boy once, albeit one who did not fit into the standard masculine model. I didn’t play or watch sports (because I wasn’t interested), and the competitiveness that comes with standard masculinity struck me as a complete waste of my time and energy.

Had I grown up in the US, I have no doubt that I would have been relentlessly bullied by the “jocks”. But I lucked out and grew up in West Germany. It’s not that there’s no bullying in Germany. But it’s not part of the overall fabric of society in the way it is in the US where bullying essentially is part of the wider culture. When I first came to the US, I was shocked how by the open and completely uncritical depiction of bullying in popular culture, which, of course, is also connected to coarse, violent language being equally accepted (“let’s kick some ass!”).

I remember that being a teenage boy placed me in this strange spot between being a child — with its world of play and make-believe — and being an adult. In my own ways, I’d try to navigate the possibilities, even as I was aware — as teenage boys are — that it is the adult world that is to be emulated. The energy of child play got transferred into anything that was filled with adult possibilities, and inevitably that meant violence and power.

Teenage boys aren’t the greatest judges of their own (or other people’s) responsibilities, and for sure they have terrible impulse control — which, if you think of it, sounds pretty much like the behaviour of the various neofascist leaders that you can find all over the world (an exception might be provided by Poland’s Jarosław Kaczyński, who pulls the strings in the background).

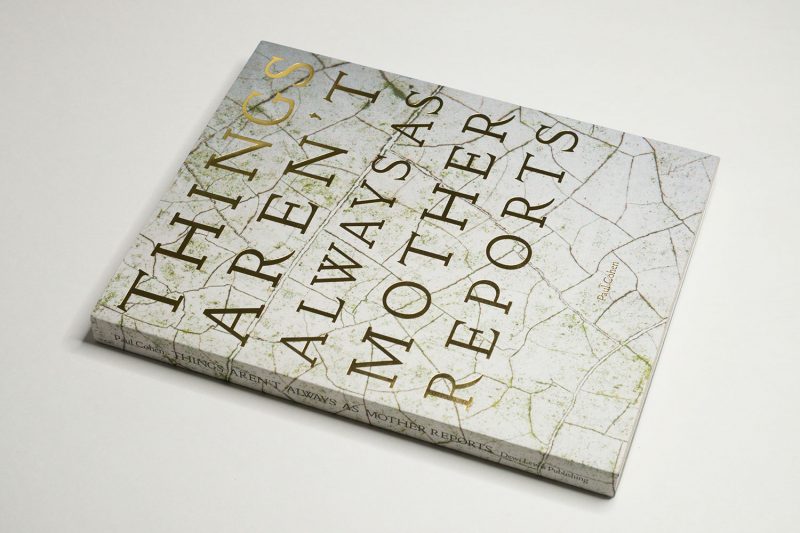

Paul Cohen depicts the conundrum he’s finding himself in as a father of teenage boys in Things Aren’t Always As Mother Reports (published by Dewi Lewis). If there is a photobook that feels incredibly relevant for that part of the world — England, it’s this one.

The book contains a lot of portraits of his sons, some tender, others filled with the kind of teenage violence that is always just a short step away from actual disaster. In addition, there’s the world these boys grow up in — London. From that environment Cohen extracts traces of things that might reflect his own struggle: trying to be a good father for his own children. There’s neglect in the lived environments, which manifests itself in a number of ways: crumbling buildings or infrastructure, but also traces of the people affected by it.

Consequences of violence are frequent: there’s a picture of a burned out house, a row of what look like police technicians looking to collected evidence of some violent crime (right next to them, a bouquet of flowers is propped up), a small graffito in support of a fascist party on an advertising poster, and more.

Even as the book ends on a hopeful note — one of the sons is shown against a bush of roses, his hands stretched out towards the sky with his eyes closed, it’s not clear whether things will end well. Cohen’s conundrum is shared by other parents: how do you raise your children in a world that is ruled by people filled with disdain for all things that help people be better people? I have no idea.

The book also conveys a sense of possibility. I’m reluctant to use the word “hope”, in part because it has become such a cliche in US journalism and writing that concerns itself with our times. Mind you, in principle hope is good — but it ought to be more than the equivalent of a sentiment on a Hallmark card.

Maybe this is a projection on my part (I know Paul Cohen quite well). But I sense that he knows that things are going to be alright for his boys, because as a father he has done the best job he can.

Recommended.

Things Aren’t Always As Mother Reports; photographs by Paul Cohen; essay by Val Williams; 104 pages; Dewi Lewis; 2021

Rating: Photography 4.0, Book Concept 3.0, Edit 3.0, Production 4.0 – Overall 3.6

Ratings explained here.