Peter Hujar is one of the most underappreciated American photographers of the late 20th Century — certainly when compared with those pushed by MoMA’s John Szarkowski, whose by now often stale wares are still being frequently exhibited. Hujar’s world isn’t governed by tiresome machismo. Instead, it’s infused with tremendous sensitivity to who or whatever might have been in front of his camera’s lens.

If someone asked me about an artist who is or was good at photographing animals, my immediate first choice would be Hujar. Photographing animals is a little bit like making a collage: it’s very easy to do it in an OK fashion, but it’s very hard to do it very poorly or, and this is what I’m interested in, very, very well.

I don’t think you can photograph an animal if you’re not very much aware of the presence of another living being in front of you, a living being that deserves to be treated with dignity and respect — and with love. But this is just the first step. You’ll also have to approach your subject with the recognition of its own uniqueness — a form of compassion if you will.

As a brief aside, this is why I will neither look at nor review photographs or photobooks that showcase cruelty against animals, such as, for example, bodies of work that deal with hunting: the lack of compassion is an abyss I’d rather not look into (I think as a photographer, you’re deceiving yourself when you think that photographing hunters with their trophies is entirely disconnected from their activities).

My outline of photographing animals contains the same aspects as when dealing with portraits of people (something Hujar also excelled in). But here things are being complicated by the presence of reciprocity: why should someone like Donald Trump be treated with dignity and respect, given he has never shown any in his dealings with other people?

Peter Hujar might have had an answer to this question. Given he is not with us any longer, we will never know what he would have said.

The Shabbiness of Beauty places Hujar’s pictures next to Moyra Davey‘s. It was Davey who made the selections and who developed the sequence of the book. In other words, here we have a collaboration of sorts between two unique artists, one living, one dead.

Before talking more about the photographs, I feel that Eileen Myles needs to be acknowledged as the other major contributor. Right at the beginning of the book, there is an extended meditation about the photographs that the poet wrote while engaging with them. You can read the full piece here. It’s a marvellous piece of writing that I’ve had to read several times to be able to fully grasp all of its nuances. The book’s title is taken from it.

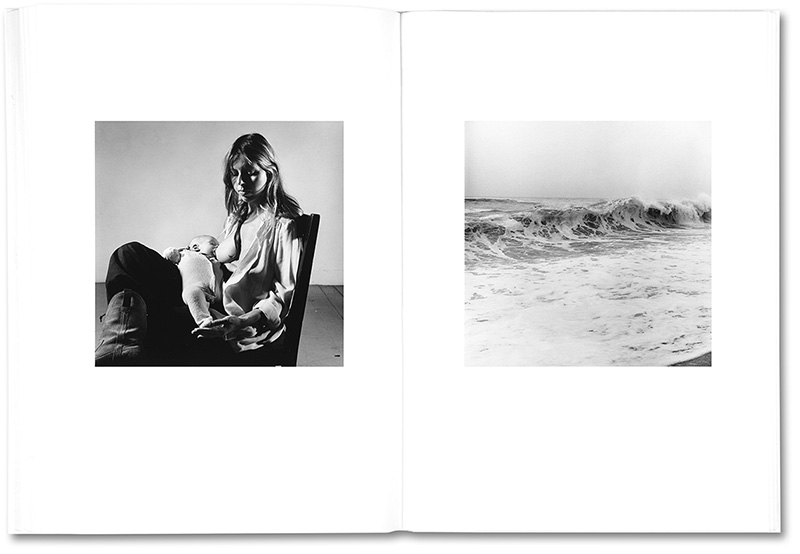

After the essay, there are the photographs. At first sight it’s not clear which ones are Hujar’s and which ones are Davey’s: there are no captions. There’s are two lists at the end of the book that provide the information. This solution was the right thing to do: captions or a reveal in situ would have destroyed parts of the dialogue.

Having looked at them many times now, I think I can tell the difference. But it’s possible that I’m deceiving myself here and there. Davey is able to approach the world with a sensitivity that is in tune with Hujar’s, even where pictures were made to correspond with his.

There are slight differences, and for the most part I couldn’t know what they are (Davey’s animal photographs aren’t as felt as Hujar’s). These differences don’t take away from the book. Instead, they serve to remind the viewer that this is a conversation. I’m interested in these differences, because they hint at the richness of photography that exists in the worlds of these two artists.

I’d love to see more of these kinds of projects, where a fellow artist dives into an archive — instead of curators or people intending to tell a story we already know. This is not to say that curators are unable to connect with an artist’s sensibility (many of them are); but they lack access to the anxiety and occasional terrors that come with the process of creation.

Moyra Davey brings what feels like endless generosity to the endeavour of putting together her pictures alongside Hujar’s. That’s not a given, either. All-too-often, encounters between artists end up being driven less by openness toward the partner and more by a sense of competition, of unvoiced rivalry.

I suppose it’s a little bit easier to approach someone’s work if they’re dead and are thus unable to push against ideas. But I don’t think that’s the case here. That’s not why this is working so well.

To some extent, my looking at the photographs is informed by the fact that I have read Davey’s Index Cards, a collection of the artist’s most recent writing. While I found the collection to be a bit uneven, its best pieces betray an artist whose looking at the world always comes with ample looking at herself (it is this aspect that’s almost entirely absent from Szarkowski’s photo-macho crowd).

Maybe this is what makes a great artist: someone who knows that looking at the world always also entails looking at herself, that taking a picture from the world means including an aspect of herself, that making a picture without a large amount of generosity can lead to good, but rarely to great results.

Highly recommended.

The Shabbiness of Beauty; photographs by Peter Hujar and Moyra Davey, edited by Moyra Davey; essays by Eileen Miles and Moyra Davey; 128 pages; MACK; 2021

If you’ve enjoyed this article about photobooks, you might enjoy my Patreon: in-depth essays about and videos of books that cover my own personal response as much as the books’ individual aspects.

Also, there is a Mailing List. You can sign up here. If you follow the link, you can also see the growing archive. Emails arrive roughly every two weeks or so.