Every once in a while, some photography comes along — or, as it typically the case, is being discovered long after it was made — that has the potential to radically change our ideas and views of a place at a specific moment of time, offering a sudden form of recognition for its audience — a moment of satori if you will.

The above is clearly the case for the photographs made by Akihiko Okamura in Northern Ireland around the low-level civil war that typically is being described euphemistically as “the troubles”. When I grew up, that war was a frequent part of the news on TV in then West Germany.

As a child, I didn’t know anything about the reality of the world. Colonialism didn’t mean anything to me, and sectarian violence struck me as absurd. I only heard about bombs going off on a regular basis or about some military roughing up protestors yet again. It was much later that I learned what was going on.

There has been a lot of photography made around the war, and I find most of it lacking. Gilles Peress’ many photographs show everything but reveal nothing. Paul Graham’s work speaks of a detached art outsider’s privilege more than anything else: it shows nothing and reveals even less. The rest of the work made in that small patch of land falls near one of those two poles: the (roughly) photojournalistic one or the arty one.

That it would take an outsider to break open the visual representation of Northern Ireland’s war should come as no surprise. As an outsider, you’re typically not anchored to precious beliefs other than your very personal ones. However, given that Okamura was a photojournalist, the fact that he managed to break free from the conventions he had adhered to earlier is in fact surprising.

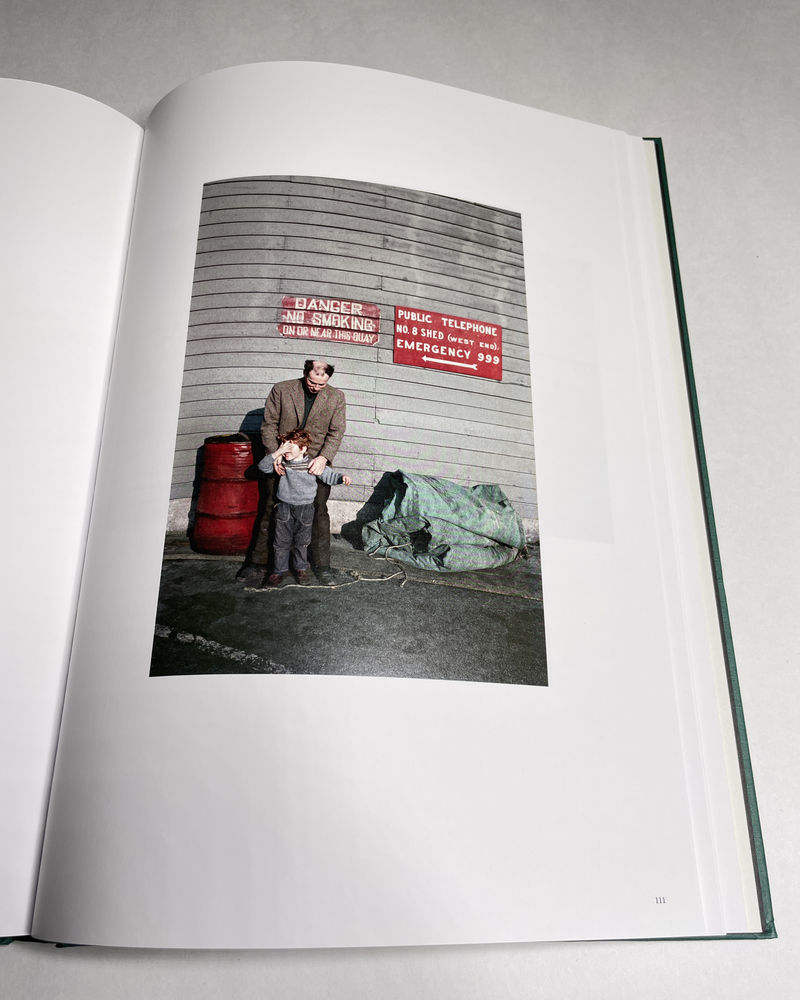

For reasons that would appear to be at least partly unknown, Okamura moved to Ireland and brought his family along. The work that he ended up making around Northern Ireland, now released as The Memories of Others, looks as if he always arrived a moment too early or to late at any of the locations he photographed. But it is in exactly those moments that a larger truth emerges about what was in front of his camera.

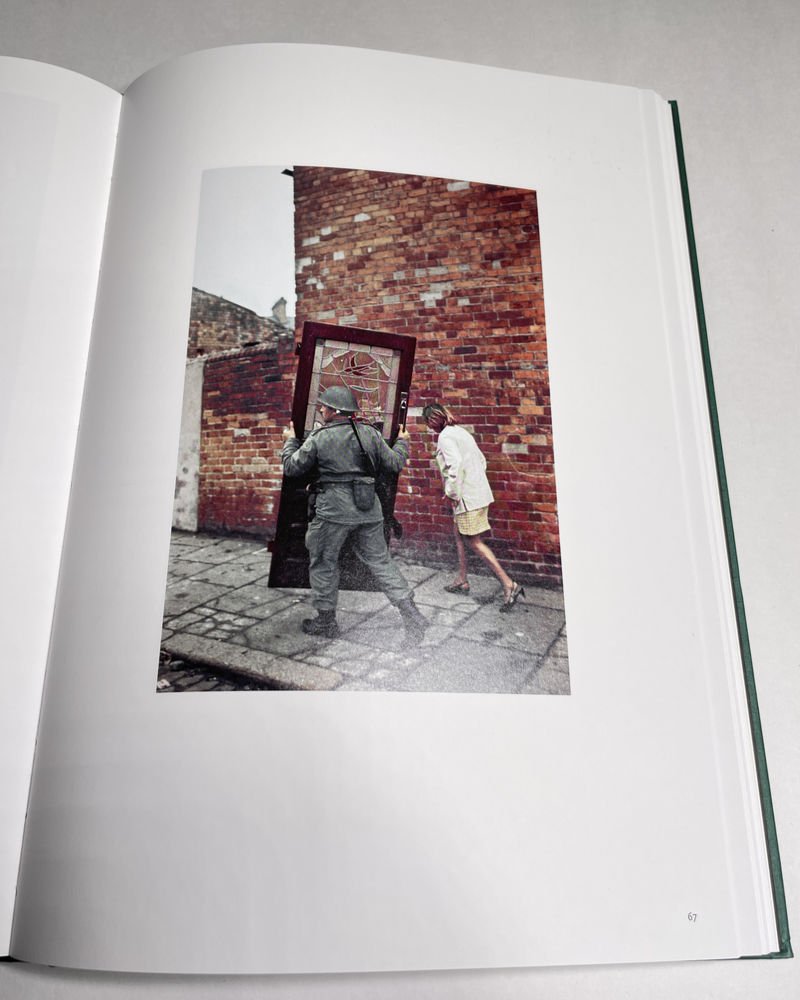

Some of the imagery made by Okamura is almost too bizarre to be true. For example, one photographs shows a soldier carrying a door while walking next to a woman. As a viewer, you want to believe that he is carrying the door for her, even though you obviously have no way of knowing. And why would the door have to be moved? In my whole life, I have never seen anyone carry a door on the streets, let alone an armed soldier.

How does that picture fit into the certainty with which observers typically look at Northern Ireland? It doesn’t. It refers to the violence — the solider is outfitted for war; but it also refers to something completely different, which in part is (or at least looks) absurd in this frozen moment. The photograph catapults us out of what we know (or we think we know) and forces us to consider other possibilities.

In another picture, two women stand in front of a burned out house. The older one of them is holding a number of empty coffee or tea cups. In front of them, there is what might be a kitchen appliance on top of which some plates are stacked. Were these items rescued from the house behind them? Or are people being offered food and drink? It’s impossible to know.

In fact, trying to find explanations might be precisely the wrong approach. Explanations only lead to certainty, and it is the irreconcilable certainties of the two sides at war that caused the horrendous loss of life, a loss of life alluded to in many pictures, such as when a black flag is being shown that is waving over two sets of flowers. Someone had lost a lot of blood and their life in that spot. The blood had not yet been cleaned up.

There is a very touching and rather sad short essay by Kusi Okamura, one of the late photographer’s daughters, at the very end of The Memories of Others. “His Irish photographs,” she writes, “hold an intimacy that his other photographs don’t have. They hold the key to where my father’s heart lay.”

I’m imagining the consolation this insight must bring, however small or large it might be, given that “he was absent for much of my childhood, away working, and died when I was just 9.” I suppose that there always is a price to be paid for photographs to be taken. It makes me feel bad that in this case, it fell on Okamura’s next of kin.

If there is one thing I took away from the book it is deep sadness that so much was sacrificed for so little. You could probably say that about every war, civil or otherwise.

Still, that’s not how we typically discuss or treat war. After all, wars usually have winners and losers, there is a good and bad etc. Sure, there is a good and bad here. And yet I cannot help but feel that in the end, everybody ended up being a loser, being poorer, being deprived of so much happiness — until an agreement in the late 1990s put an end to the violence. Despite the Tories’ recent best efforts to damage the agreement because of their “Brexit” folly it has (so far) remained in place.

The Memories of Others is filled with incredible photographs. As I’ve argued, the book can show a way forward for all those who cover what euphemistically is called “conflict”. You can’t just parachute in. Most importantly, though, you have to be emotionally involved in the place you’re trying to say something about (and not merely in your own personal story).

Furthermore, the essays included in the book provide much needed insight into what is on view and into the person behind them. They’re a delight to read because they’re well written and avoid tedious jargon. And I might as well note that the photographs have been edited and sequenced deftly so that even the many stand-out pictures still exist in the continuum of the work and context.

For all these reasons, The Memories of Others is a landmark publication that deserves to be seen widely. And Akihiko Okamura should be remembered for creating such a deeply meaningful body of work around a country far removed from the one he grew up in.

Highly recommended.

The Memories of Others; photographs by Akihiko Okamura; essays by Trish Lambe, Pauline Vermare, Masako Toda, Sean O’Hagan, Kusi Okamura; 160 pages; Prestel; 2024

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing to my Patreon. There, you will find exclusive articles, videos, and audio guides about the world of the photobook and more. For those curious, there now is the possibility of a trial membership for seven days.

Much like journalism, photography criticism involves a huge investment of time and resources. When you become a subscriber, you not only get access to more of my work. You will also help me produce it (including the free content on this site).

Thank you for your support!