In the US, it currently feels as if the country is finally getting out of an incredibly abusive relationship. With the exception of the hardcore “MAGA” crowd, everyone seems to be taking that much needed deep breath, knowing that very soon, nobody has to listen or pay attention to the malignant-narcissist-in-chief any longer. It’s not clear what will come next — there still are ample reasons to worry; but at least the noise level appears to have gone way down.

As a consequence, I’m thinking (or maybe just hoping) that we’re going to find more time for nuance again, in particular those small moments when something reveals itself that is unexpectedly beautiful. Photography is very good at dealing with that. This is not necessarily why I personally look at photographs (and I don’t think I have much hope of finding it with my own camera). However, without such photography my experience of dealing with the medium would be vastly impoverished.

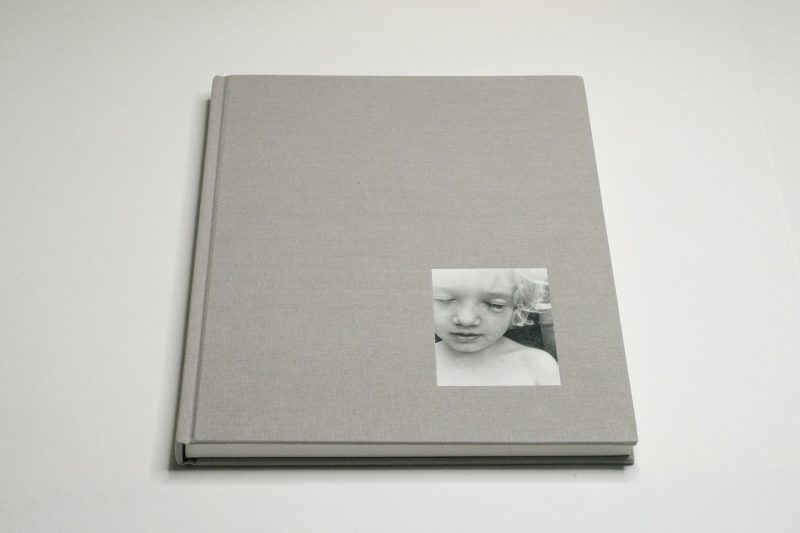

The most recent photobook to have made me think about all of this (even before the election) is Jesse Lenz‘s The Locusts. When I first received the book, I was surprised to see its photographs. The book itself is rather large and imposing — unlike the vast majority of its pictures, which depict a fragile world in a very gentle manner.

In a variety of ways (and using a variety of cameras), the photographs centre on small moments in a world seemingly inhabited only by children and animals.

In particular the square pictures are real showstoppers. In one, a little toad is shown, sitting on a leaf of much larger plant, possibly enjoying the sun. In another, a little boy with what might be a mix of a drawing and a temporary tattoo on his face looks at the camera while clinging to an apple tree bearing fruit. The pattern of the shadow cast on his body has him partly blend into his environment.

It’s precious moments like these that connect the work beyond its immediate American predecessors to other photographers all over the world who find beauty in small moments that won’t last long and that might not be seen by anyone else. I’m thinking of Rinko Kawauchi, for example. There are many small moments in most of the photographs. As Kawuchi has demonstrated, that already would have been enough for a good book.

But The Locusts adds other elements. There are many pictures of children playing. When you’re a child, the world is your playground. I don’t know at what stage one loses this approach to one’s surroundings — I suppose at a certain age, you’re just “too old” for this (which, if you think about it, really is a shame — maybe we’d collectively be a little bit happier if we regained our sense of play).

And then there is mortality. In the bucolic setting the photographs were taken in, death is a lot more visible than in a city. Here it appears in the form of a dead coyote lying in a field or, one of my favourite pictures, a black cat staring intently at a little mouse right in front of it. In one picture, a child holds a (different) cat, and two pages later, there is a photograph of what looks like the same cat being prepared for burial — a cardboard box with what looks like a towel wrapped around the body serves as the coffin.

I never had children. But I’m guessing that for all the work and worry of raising them, they also offer bringing a sense of the world’s possibilities and joys — if, that is, one is receptive to it. One doesn’t need a camera to pay attention to what the world has to offer, but sometimes, having one helps. Lenz appears to have had at least one available on many occasions, which for sure explains the plethora of work on display in the book.

While I feel that the book probably should have been a little more intimate and not quite so hefty, and the edit could have been tighter, The Locusts for sure is an impressive debut book by a photographer who I’m sure we’re going to see and hear a lot more of in the future.

The Locusts; photographs by Jesse Lenz; 144 pages; Charcoal Press; 2020

Rating: Photography 4.0, Book Concept 2.5, Edit 1.5, Production 5.0 – Overall 3.5

Ratings explained here.