If, like me, you have a hard time remembering people’s names, reading history books becomes a real chore, especially in cases such as Japan. There, for the longest time the ruling class played elaborate games with the idea of power, all of them of course at the expense of those not typically mentioned in history books at all: all those thousands of people listed as numbers in battles and all those millions of people whose job it was to sustain all of it.

Furthermore, the ruling class also created a bizarrely complicated power structure for the country, with emperors resigning the moment their heirs were old enough to take over, only to then continue ruling behind the scenes as “retired” emperors (often “cloistered”). This immediately doubles the number of characters because each emperor of course needed his own court (power structure). You thus get twice the number of names, a game made even more complicated by not uncommon name changes.

But power did not always reside with an emperor at all, whether retired or not. Other figures — it’s easiest to think of them as warlords — jockeyed for influence in a variety of positions, whose actual amount of power would shift as well. At some stages, being a shōgun was mostly meaningless. At other stages, you were the man (and yes, it’s almost all centered around men).

When Tokugawa Ieyasu reunited the fractured country in 1603, creating what became known as the Edo period, his most important achievement for the ruling class was the elimination of all of those power games. For the rest of the country, it meant peace, a peace that had been elusive for so long.

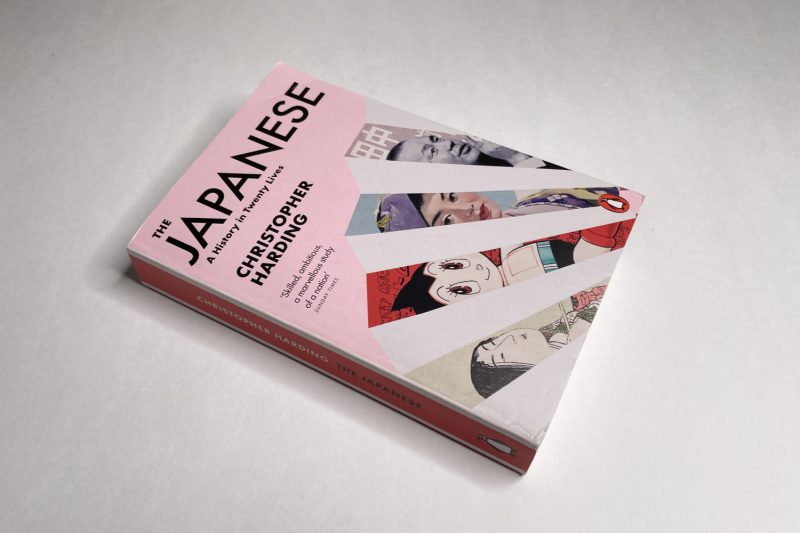

You would imagine that an arguably seminal figure such as Tokugawa Ieyasu would be featured prominently in a book that is centered on the lives of 20 Japanese people throughout the country’s history, but he is absent. As it turns out, Christopher Harding‘s The Japanese — A History in Twenty Lives is not your ordinary history book. Harding is a cultural historian. Consequently, the country’s culture features very prominently in the book.

For those eager to learn about the reunification, there is a chapter on the first of the three warlords who sewed the seeds for what Tokugawa would harvest later. In his earliest years, the fiendishly brutal Oda Nobunaga was simply known as “the fool”. Thankfully, the book only briefly mentions some of the brutality this particular man engaged in.

I have always considered it as a shortcoming that so few history books deal with anything other than power. For example, you can understand parts of Germany’s history through its rulers. But you will still not be able to understand why certain things evolved as they did and why the country even today is so insecure about its own identity. In the very different context of Japan, you could make the same observation.

Located near the much older and usually much more powerful Chinese nation, the Japanese looked to that region for inspiration in any number of ways, whether in terms of religion or culture. In fact, for the longest time the Japanese ruling class would learn and speak Chinese, adopting Chinese script to write their own language (for which previously there simply was no script).

The court was so engaged in cosplaying another country’s culture that what would turn out as one of the defining pieces of Japanese culture was produced by someone who had no real part in any of that: Murasaki Shikibu is one of the early characters in The Japanese. Her real name is unknown. “She was born around 973,”Harding writes, “at a time when it was considered poor form to record — or even use, in public — an aristocratic woman’s personal name.” Unlike the cosplaying aristocrats around her, Murasaki Shikibu left a lasting impression in the form of The Tale of Genji, arguably the world’s first novel.

Harding’s use of writers, monks, travelers, inventors, or financiers is masterly: instead of telling the story of Japan as one of battles and court successions and land reforms, it becomes one of people, around whom things are happening and who have a role, whether small or sometimes large, in it. Some of the stories are almost too fantastical to believe, such as Hasekura Tsunenaga’s travels to Europe via the Americas to meet with the pope some time in the early 1600s.

As a consequence, if there’s one overarching achievement — besides providing the sheer joy of reading an incredibly engaging book — The Japanese does the country a huge service. All too often, Japan is seen in the West as something that is just different; Orientalism — whether of the malign or now mostly benign kind — is never far away. By presenting the lives of twenty people, most of them as ordinary as extraordinary, for the reader any otherness encountered is always only the otherness of the past, an otherness that we all know from our own personal histories.

For this writer and photography critic, the book also hit a different note. Over the past few years, I have become very interested in Japan. But I have also become rather disenchanted with the fact that photography is usually discussed in ways that is not too dissimilar from how history is discussed. That photographers are embedded in their societies and that they often are deeply affected by them too often is simply ignored.

To stay in the context of Japan, I personally couldn’t care less about the Provoke movement’s use of blurry and grainy photographs if there is no mention of how the photographers got there in the first place, what the aesthetic actually says about its time, and what ideas were being played with by some of its practitioners. That way, the movement becomes a lot more interesting, because it speaks of a very particular time in recent Japanese history.

How such a retelling could be achieved is demonstrated by Christopher Harding in The Japanese — A History in Twenty Lives. Even if you’re not at all interested in the country, I suspect that you will still enjoy reading the book. Ultimately, it’s a collection of people’s aspirations, some fulfilled, others not; and not all heroes (if that’s even the right word here) remain untainted by their times.

Highly recommended.

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing to my Patreon. There, you will find exclusive articles, videos, and audio guides about the world of the photobook and more. For those curious, there now is the possibility of a trial membership for seven days.

Much like journalism, photography criticism involves a huge investment of time and resources. When you become a subscriber, you not only get access to more of my work. You will also help me produce it (including the free content on this site).

Thank you for your support!