It’s probably fair to say that the one place that has most severely been photographically misrepresented is the continent of Africa. There are many contributing factors, most notably, of course, colonialism. The European colonial project relied on the camera for its purposes, defining to a large extent how Africa was to be seen. But it doesn’t stop there.

Western photojournalism played and still plays a major role in the continued misrepresentation of Africa. It doesn’t matter at all whether photojournalists went or go to Africa with the best of intentions (as they typically do); what matters is that many of them appear to be oblivious of the issue at hand.

One of the key approaches to rectifying the situation entails looking at the work of local photographers. How have photographers born and working in Africa portrayed the people in the various countries they were and/or are living in?

In photoland, this approach is typically broadly described as centering on a person’s gaze. It’s likely that you will be familiar with the term “the male gaze”. But you need to be careful with that term, because the male gaze is not identical with a man being the photographer. What it means instead is that the world is portrayed in such a fashion that the visual representation conforms to how an assertive heterosexual man views it. As is very obvious from the world of fashion photography, women photographers can easily re-produce the male gaze.

In much the same fashion, to discover the African gaze you need to go deeper as well. Photographers from Africa can easily produce what you might want to think of as a neocolonial view of Africa (the most obvious example is provided by some of Pieter Hugo’s work).

The following might be tad naive, but it still might serve as a good initial approach to how to distinguish the neocolonial view from a real African gaze. The former is produced for outsiders (in Hugo’s case, a Western art market interested in pictures that look good over wealthy collectors’ couches). The latter is produced for a local audience (even if it could eventually reach an audience outside of Africa).

Amy Sall‘s new book The African Gaze provides a most welcome overview of some of the richness produced by photographers and filmmakers from Africa.

I should note that in the following, I will focus on the first half of the book, photography. This is because I know next to nothing about film making in general. I don’t mean to imply that film making is not interesting. It might well be. I simply don’t watch many movies. As a consequence, there’s nothing of any value that I could say about them. I am in no position to assess the second half of the book in any kind of critical capacity.

In a nutshell, The African Gaze contains introductions to 25 photographers and 25 filmmakers. In the photography case, the artists hail from Algeria, Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Congo, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Mali, Nigeria, Niger, Senegal, South Africa, Sudan, and Uganda (several countries are represented by more than one photographer).

Individual biographies might be more complex. For example, Augustt Azaglo Cornélius Yawo was born in Togo. He spent his childhood and formative years there and in Ghana. He then became a prominent photographer in Côte d’Ivoire after he settled in that country at age 31.

For sure, some of the names will be more familiar to a Western audience than others. Malick Sidibé’s work is relatively well known in the West (not necessarily compared with Western artists but certainly when compared with photographers from Africa), as is Ernest Cole’s, Samuel Fosso’s, or James Barnor’s.

One of the most interesting aspects of looking through the book — besides the discover of any number of incredible artists — is understanding the many shared sensibilities between the photographers, since it connects the known names with the lesser known ones and their background.

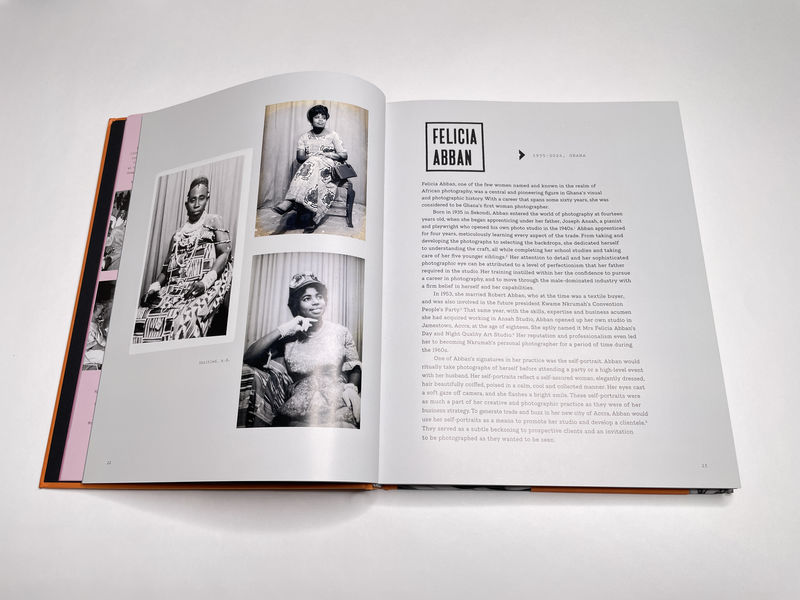

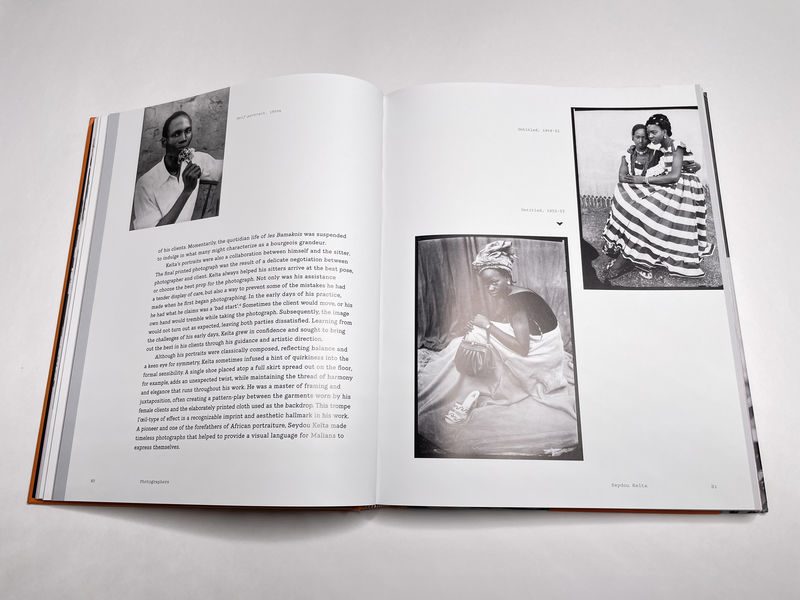

The business of the photography studio provides the most prominent backdrop of vast parts of the work showcased in The African Gaze. The photographs in question were commissioned by people coming to the studios who wanted to have a visual keepsake — much like how in other parts of the world photo studios played the same role.

The role of photography studios is possibly underappreciated in photoland for any number of reasons. Where photo studio artists have become known, it’s mostly because of the perceived exoticism of their work — and this is not necessarily only the West looking at the rest of the world. Reading about the work of, for example, Mike Disfarmer, I usually can’t help but think that it’s the perceived exoticism of those in the photographs that provides most of its appeal.

Of course, there also is the fact that given its very traditional and conservative leanings, photoland demands that photographers be artists, and an artist is supposed to be independent of the whims of the people paying for their work (however laughable an idea this is once you look at how the art market works). A true photolandian portraitist must insist on their own artistic genius over what their sitters want. Throw in some classism, and thus the whole rich genre of the photo studio is mostly relegated to the dustbin.

If as a viewer, you’re able to free yourself from how photoland views photography studio work, The African Gaze has much to offer. Time and again, the photographers were able to produce the most amazing work, even as they often eschewed what elsewhere were considered photo-studio conventions.

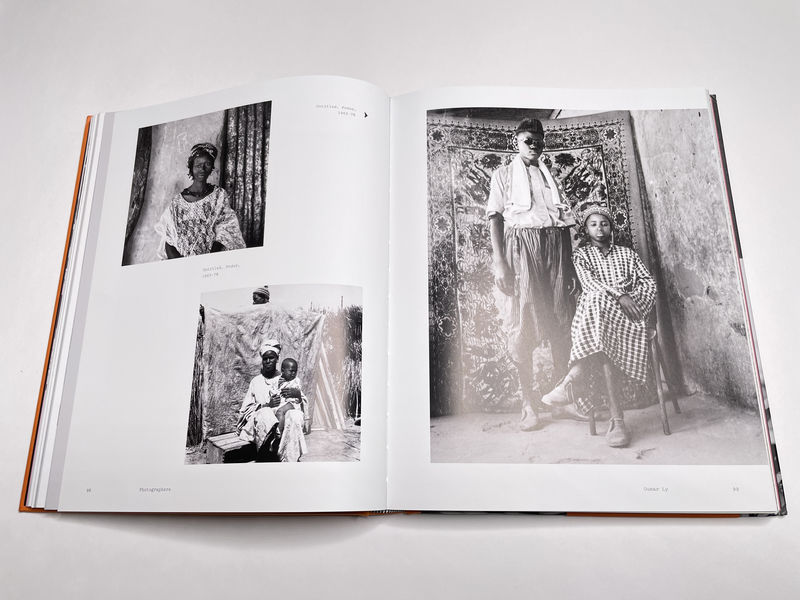

In maybe the most exciting such example, Oumar Ly’s assistant spread his arms while standing behind a young woman holding her young child, creating a backdrop with the fabric of his garment. In Ly’s framing, the assistant’s head and left hand remain visible, as does part of the background. The resulting photograph is a portrait of a woman and her child. But it also is a portrait of a life situation — the complete opposite of the family propaganda that was so commonly produced in the West.

This is the main point of The African Gaze: how you look at someone (and with what ideas in mind) determines what you will see. A whole continent narrowly defined using racist ideas can only emerge on its own terms if it is allowed to do that, if, in other words, it is encountered on its own terms.

The photographers in the book — in combination with those who commissioned their work — set those terms, terms that not only enrich our understanding of Africa but also challenge some of the ideas we have adopted for the depictions of ourselves.

Recommended.

The African Gaze; images by various artists; essays/texts by Amy Sall, Mamadou Diouf, Yasmina Price, Zoé Samudzi; 288 pages; Thames & Hudson; 2024

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing to my Patreon. There, you will find exclusive articles, videos, and audio guides about the world of the photobook and more. For those curious, there now is the possibility of a trial membership for seven days.

Much like journalism, photography criticism involves a huge investment of time and resources. When you become a subscriber, you not only get access to more of my work. You will also help me produce it (including the free content on this site).

Thank you for your support!