For a world of photography that professes to be interested in diversity and in exploring the role text can play for and with pictures, there were surprisingly little discussions of Sophie Calle’s work up until recently. Recognition of her achievements is now arriving, though. Calle won the Hasselblad Award in 2010, and at the time of this writing she is on the shortlist of the 2017 Deutsche Börse Prize. Still… I can’t help but feel that having a little less of the usual suspects (Walker Evans, Robert Frank, et al.) and more of those equally strong voices, such as Calle’s, would help breathe life into our ideas of what photography is and does.

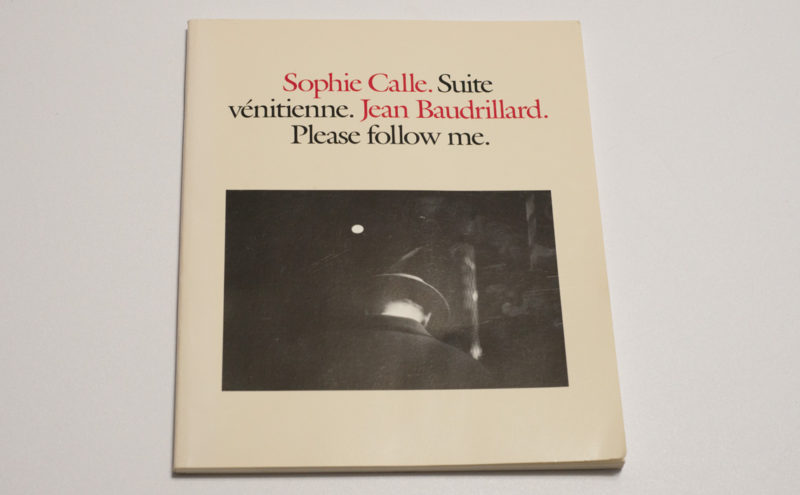

Of late, I have spent a lot of time with books made by this artist, the most recently published one being And so Forth. There have been various reissues and (re-)compilations of older books, some of which I bought. And so Forth is such a compilation of material, but it was all new to me. However, the most recent book I bought is older, dating from 1988 (in its English language incarnation), Suite Vénitienne/Please Follow Me.

For reasons that aren’t entirely clear to me, I ended up hunting for the original 1988 paperback instead of the 2015 reissue. It might have been just the pleasure of the hunt. Copies can be had on US eBay for around $130 or more. But I have a strict $100 spending limit for a(ny) photobook. I lost a bid on a signed copy a few weeks ago when it sold for $75. But not that much later, there was an unsigned copy listed for $29.99, and nobody else bid on it. So it was mine.

There is a world between And so Forth and Suite Vénitienne. It’s not just the difference in time, and really, I’m comparing apples and oranges, or rather a big basket of apples with a single orange. Not knowing how big Suite Vénitienne would be, when it arrived, I was surprised how small it is. Somehow, I had thought it would be bigger. I don’t know why. And so Forth is a veritable brick of a book, whose edges are reinforced with metal linings no less. You could hit someone over the head with the book (please don’t!) and do some serious damage. If you attempted to slap anyone with Suite Vénitienne (again, don’t!) I suspect all that would happen is possibly some laughter.

I wrote elsewhere about how the form of a book matters. Suite Vénitienne feels light in the best possible way, even though the work itself doesn’t. This is not to say that the work is grave. It’s not. But it’s conceptual in the way that all of Sophie Calle’s work is conceptual, while being light and infused with deep humanity at the same time. It is, in other words, a far cry of, let’s say, the overblown heavy-handedness that runs through the work of Taryn Simon, to name another conceptual photographer. Calle manages to bring a smile to my face even where she makes me cry. In contrast, I find Simon’s work exasperating and, to be honest, mostly boring.

Maybe if we all thought of Sophie Calle when discussing conceptual photography, that field would find a lot more dedicated followers. As far as I can tell conceptual photography has the reputation of being made for people who laugh on command. I know, that’s really not a fair statement. But let’s face it, that’s what it feels like, doesn’t it? And then comes Sophie Calle, and you realize how a completely conceptual approach, a strange set of rules that might or might not seem to be overly restricting can result in the world unfolding in all its glory in front of you. It’s quite amazing.

“For months,” writes Calle, “I followed strangers on the street. […] I photographed them without their knowledge, took note of their movements, then finally lost sight of them and forgot them.” Reading this in 2017, one can’t help but think that this is a bit strange, if not dodgy. But then, the issues of surveillance and privacy, of getting to know what is supposed to be unknowable, lie at the heart of this artist’s work. “At the end of January 1980,” Calle continues, “on the streets of Paris, I followed a man whom I lost sight of a few minutes later in the crowd. That very evening, quite by chance, he was introduced to me at an opening. During the course of our conversation, he told me he was planning an imminent trip to Venice…” Of course, Calle would have to follow him. In fact, the sheer logic of that act makes this all very Sophie Calle: in her world, the only obvious step is to follow the man to see what he’s doing in Venice. That’s the book, Suite Vénitienne.

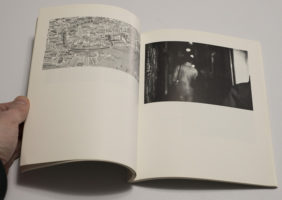

The photographs in the book aren’t its important aspects. They’re not necessarily the greatest photographs. Approaching the work with the idea of great photos in mind would miss its point. In Venice, Calle shadowed her person of interest, whom she indeed managed to track down. A lot of the pictures were taken while she followed him (and his wife) through the streets. They’re surveillance photographs, with Calle acting as a private detective of sorts (this included a disguise in the form of a blond wig).

The pictures come with text, ample text, and it really is here where the artist shines. The writing is brilliant. It’s poignant and moving, it’s clever while hinting at its maker’s various vulnerabilities. It frames the photographs and makes them a lot more interesting than they actually are.

In/with Suite Vénitienne manages to turn a viewer/reader who originally might have recoiled at the very premise of following someone and photographing him not only into a willing accomplice, she makes her/him into a co-conspirator. The viewer/reader can’t help but root for Calle, who somehow morphs from being an artist into a woman on a conquest for a man.

This is what lies at the core of why this particular artist, as conceptual as most of her work might be, manages to elevate the work out of dry conceptualism (the one with laughter on command) into something entirely different. The conceptualism — the at time strange or droll rules — aims at the most human of our desires and dreams. Even seemingly irrelevant details are made to acquire stinging meaning. For example, her disguise, the blond wig, takes on its own role: “I go back to my pensione. On the way I take off my wig. I meet the man who had followed me as a blond. He doesn’t pay any attention.” (p. 20)

For Sophie Calle it is exactly this switch that creates part of her work’s poignancy, where seemingly mundane or irrelevant details are not just given some minor role. Instead, they are made to reveal something about the artist’s own vulnerability: here, it’s not just about following some man any longer, it’s also about the flip side, about desiring and being desirable, about the various things that are tied to it.

In Calle’s work, the combination of text and photographs operates along the best lines of visual storytelling there is in the world of photography — if, and this might be up for debate in certain quarters, it can be easily seen as being part of that world (I’d argue it can). Text and photographs complement each other. The text might work without the images, but the other way around you’d lose everything.

The photographs, while usually not in that realm of amazing pictures, still add not only just enough, in fact they kind of are amazing pictures because they’re so banal. They don’t draw attention to the effort needed to make them. They’re documents more than anything. They’re deadpan, but they’re poignant at the same time. And they’re being brought to life through the text.

As a photographer thinking about text plus photographs, you’d be well advised to spend a lot of time with Sophie Calle. It will take some will power to look beyond the charm and strength of this artist’s work. It all looks so effortless, too. I’m sure it’s not — or maybe Calle is one of those people for whom the most amazing things just come easily. Either way, there are millions of ways of telling stories with photographs and text. Here’s an example where both are given more or less the same weight, elevating each other with charm, wit, elegance, and always a hint of the sadness about the frailty of human life.