We are so used to handling printed matter that we do not pay much attention to its physical properties. Looking at a book requires work: you have to hold it or use a table for support, and you have to turn the pages. But we’re used to the work, so it doesn’t register. It is when a book deviates from its basic, standard form that this aspect of our engagement becomes vastly amplified. Suddenly, we notice the work that goes into our engagement with the object, and we note the details of its physicality.

In the world of the photobook, this particular physicality has the potential to become essential for a book’s experience. Take Kikuji Kawada’s The Map (I’m talking about the original). The book was assembled using a unique construction. Every other spread contains gatefolds on both sides. There is an image, and when you open up the gatefolds, there is another one (occasionally there might be two, but they’re usually so fused that they communicate as one).

You can only appreciate the construction’s effect when you handle the book yourself. Looking at the book requires considerable amounts of work. But since the unfolding and refolding of the gatefolds happens in such a regular fashion, after a short while, a routine sets in that becomes oddly mesmerizing. The act of moving your hands acquires its own significance, and the act of looking at the book takes on aspects of meditation.

As the later two-book version demonstrates, if you take that aspect away from The Map and if you organize the photographs by category, you destroy most of the work’s magic. In one case, the work is a piece of art, in the other it’s a not very interesting photography catalogue.

The Map might be an extreme example; even so it points at the essential fact that every aspect of the physicality of the book matters: the book itself, the object, can help communicate the work’s ideas and feelings. That’s why generic photobooks, books produced without spirit and feeling, are so bad. It’s what in the past I referred to as the Tupperware approach to making a photobook, where you dump the pictures into a generic container and call it a day.

Let’s say you’re a photobook maker and your task is to make a book that communicates a voyage along a river. How would you go about this? In the most basic fashion (and that’s probably the route 99% of photobook makers would take), the sequence of photographs in a book can be seen as such a voyage. That’s very pedestrian, but it works.

But let’s say that you’re a photobook maker and you’re ambitious. Is there a way to make a photobook where the physical form of the book helps drive home the point of such a voyage? Well, yes, there is.

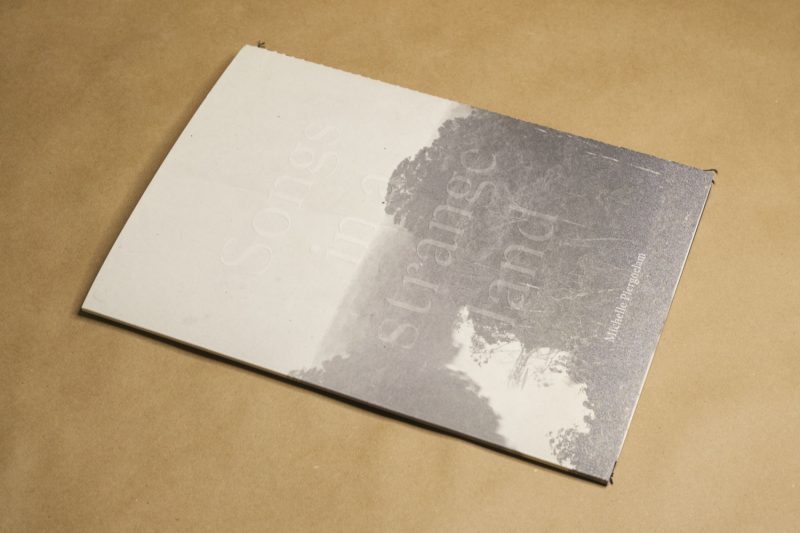

Michelle Piergoelam‘s Songs in a strange land is a roughly letter-sized softcover book that, when opened, reveals two sides. The left side of its interior contains the book’s essay, printed on a single folded sheet of paper that is sewn into the case. If you pay careful attention, you’ll admire the precision with which the images on the outside align with the images on the cover itself.

The right side of the book reveals what at first comes across as a dark block with some text on top. You can unfold it on its left side, to encounter more darkness and more text. If you look carefully, you will see some details in the darkness — leaves. But you need to unfold the block (let’s call it that) again and again to arrive at what you could think of as pages. By now, the book has become a lot wider than its original form, and unfolding the pages doubles its width yet again.

You will realize fairly quickly that you’ll need a table to look at the book (the floor will do, too). Please note that these photographs only show very small sections.

There are four pages to turn. Four doesn’t sound like such a huge number: do you know any books with this few pages? But when engaging with the book, you’re already in a world where such considerations are mere trifles. Each of the spreads (if that’s what we want to call the unfolded sections) presents a distinct set of imagery.

The first shows a boat, a river, a person, some leaves — all of that in darkness, with dark blue tones revealing what little the eye can make out. There are four photographs of a pair of hands engaged in different gestures in the next spread. After that, the person again (it must be the same as in the first), but now you’re made to sit behind him in the boat, and there is more colour (albeit not much). The final spread shows his face three times, and there must be a song that is sung. Next to it, there are what look like photograms (leaves etc.).

Folding the book back up, you might pay more attention to the dark pages (at least that’s how I first approached the book). There’s text on them. It’s a song.

From the above, it might be clear that the act of looking at the book provides an essential part of how it works. The book is delicate, requiring careful handling (or maybe that’s just me, I don’t like to tear the pages in my books). Its meaning literally unfolds in front of your eyes.

But the object itself also is very beautiful. Those long spreads work very well purely in a visual fashion. They do what a standard book would never be able to do. This is photobook making at its finest, here through the concept/design developed by Sybren Kuiper.

Songs in a strange land uses river travel as a device to address the lives of slave under Dutch colonial rule in Suriname. Thousands of people had been abducted from their homes in various places in Africa, transported across the Atlantic under the most brutal conditions, and made to work the plantations the Dutch used to build their colonial/financial empire. In Suriname, a locale filled with rivers, river travel played an integral part of the endeavour.

Songs brought from their ancestral homelands — now far away — played an important role for those having to live under the most brutal conditions. “Dawn,” some of the text reads, “brought them hope for better lives / And their songs still echo on the rhythm of the water”. Of Surinamese descent but born in the Netherlands, Piergoelam originally knew very little of that country. Her work has centered on attempting to get closer to the lives and experiences of those whose stories she alludes to.

For all these reasons, Songs in a strange land is an absolutely essential photobook. It combines the best aspects of photobook making with a very contemporary way to tell a story that needs to be told.

Highly recommended.

Songs in a strange land; photographs by Michelle Piergoelam; essay by Alx van Stirpriaan; 36 pages*; Lecturis; 2023

*please note that given the construction of the book, the page count is rather irrelevant

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing to my Patreon. There, you will find exclusive articles, videos, and audio guides about the world of the photobook and more. For those curious, there now is the possibility of a trial membership for seven days.

Much like journalism, photography criticism involves a huge investment of time and resources. When you become a subscriber, you not only get access to more of my work. You will also help me produce it (including the free content on this site).

Thank you for your support!