“No new photographs until the old ones have been used up,” Joachim Schmid decreed in 1989. His idea was not to be taken literally — at least that is my read. Instead, Schmid implored us to look more carefully at the photography that already surrounded us, to understand what it tells us.

As I’ve argued on this site beforee, this approach also entails looking at the photographs that should surround us, the photographs taken by all those who up until now have mostly been finding themselves at the margins of the written and discussed history of photography. Geography here plays a major role in defining the margins in the world of photography — even in Europe.

In particular, once you cross what four decades ago was the demarcation provided by the so-called Iron Curtain from the West to the East, there is a sharp drop off of visibility of artists. Artists might have worked for decades, making incredible work, but the world of photography — still dominated by Western European and US American power players — is slow to embrace the incredible richness of photography practiced in countries that formerly de facto were occupied by the Soviet Union.

In my understanding as someone who grew up in West Germany, dealing with photography made in East Germany has to be done with particular care and attention. On the one hand, of course these photographers deserve their spot in the canon just as much as those from the West. They deserve to be placed into the established history, to be evaluated using the same high standards. At the same time, given that these standards and references were largely formed before the Wall came down, they are very Western-centric.

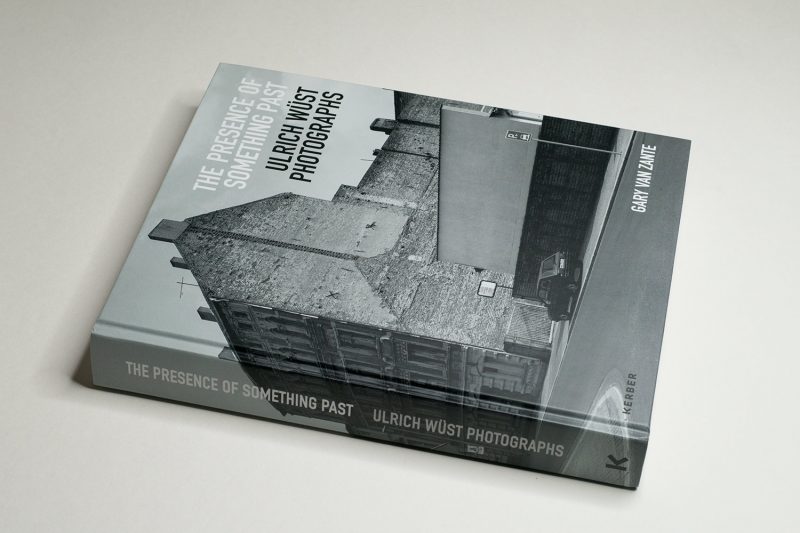

Looking through The Presence of Something Past, a career retrospective of Ulrich Wüst, drove home this particular point to me (full disclosure: the book was produced by Kerber Verlag, the publisher of my book Vaterland). What people refer to German reunification in reality was little more than a semi-hostile takeover of East Germany by West German elites. The ramifications of that takeover are likely to continue to poison Germany’s well being for many more decades. East Germans were mostly pushed aside. I don’t think their struggles to accommodate to a completely different way of life was even remotely understood by Western Germans (I’m writing this as someone for needed a couple of decades to grasp this basic fact).

Thus on the one hand, adding Wüst’s incredible pictures to what people understand as German photography is an essential task. It not only elevates the artist to the position that he deserves. It also enriches our own understanding of both German photography and East Germany itself. On the other hand, I believe that one has to be incredibly careful to give the artist’s background full consideration and to avoid insisting too much on comparisons with the usual Western photography suspects. While such comparisons can yield photographic insight, they are of limited utility when it comes to what is actually depicted in the pictures.

In actuality, though (assuming one has the mental flexibility), there is no real conflict. If you take Wüst’s Stadtbilder (translated as Cityscapes), possibly the artist’s most well known work, comparisons with artists such as Lewis Baltz, Walker Evans, and Stephen Shore are inevitable. Wüst himself took some inspiration from these Western artists (or maybe it might be better to say: Wüst felt a kinship with them).

But one needs to be careful to note the vast differences as well. These differences cover the tools used, the artists’ professional backgrounds (Wüst trained as an architect/city planner), specificity of subject matter, and more. These Cityscapes are New Topographics in East Germany, and yet they also are not. Papering over the differences for the sake of art-historical filing runs the risk of diminishing Wüst’s achievement.

As a West German, I don’t think I will ever have a full understanding of what it meant to live and work in East Germany. There is an interview with Ulrich Wüst at the end of the book that drove this point home to me. The artist makes it clear that the kind of black-and-white understanding that a Westerner might have can only serve as a cartoonish image of his own lived reality.

One might wonder to what extent any of this might matter, given it’s the work — the photographs — we should be paying attention to. But that’s exactly the point: if you only know Wüst’s Cityscapes, then you only know a very small fraction of his work, whose breadth is fascinating in more ways than one.

For example, Wüst also used a compact 35mm rangefinder camera (an Olympus XA) to document his daily life in East Berlin, in particular in the then run-down neighbourhood of Prenzlauer Berg (which since reunification has been gentrified into what only can be described as oblivion). More recently, the photographer documented the state of various East German cities and areas in reunited Germany, bringing the sensibility he established decades earlier to the much changed country he is finding himself in now.

Thankfully, the extended essay by Gary Van Zante at the beginning of the book allows access to a huge number of details about this photographer’s life work — his background, motivations, ideas, but also possible references and ways to understand the work. Even as I felt that occasionally, Van Zante embraced Wüst conforming to the medium’s (and the usual suspects’) established history a bit too much (your mileage might obviously vary), the essay manages to successfully set the stage for a viewer who might not know anything about either this artist or the country he grew up in. It’s an essential piece of writing that deserves to be read widely.

Furthermore, there are introductions for the chapters that each focus on one particular body of work. If there’s anything I have to complain about it’s that I would have loved to see even more of Wüst’s work — obviously an impossible task, given that there already is plenty. Maybe there will be more books with a focus on some of the individual projects that have not yet been published. One can only hope.

One can also hope that books such as The Presence of Something Past will now be made for other artists that grew up on the Eastern side of the Iron Curtain. Obviously, there is a rich repository of such artists not just in East Germany but also beyond.

If there is value in photography, then it can only be what allows us to grow into better versions of ourselves. Those who have gone through that process in the context of their own life work have much to offer, in particular if their life circumstances were markedly different than ours. We need to look at what they have produced not merely to acknowledge their life work, but also to be able to grow ourselves.

I would argue that in this particular case, the need to look is particularly important for West Germans, the people who allowed their leaders to crowd out East Germans on that balcony in Berlin when they celebrated “reunification” on that night that is remembered so fondly.

Highly recommended.

The Presence of Something Past; photographs by Ulrich Wüst; text by Gary Van Zante (incl. an interview with Ulrich Wüst by Ulrike Heine and Gary Van Zante); 320 pages; Kerber Verlag; 2022

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing to my Patreon. There, you will find exclusive articles, videos, and audio guides about the world of the photobook and more.

Much like journalism, photography criticism involves a huge investment of time and resources. When you become a subscriber, you not only get access to more of my work. You will also help me produce it (including the free content on this site).

Thank you for your support!