There’s a photograph of Mikiko Hara that shows the artist posing with the tool of her trade, an old fold-out camera without a viewfinder that she carries on a rather short strap around her neck (you can find the photograph here, scroll down past her pictures). A few years ago, I was able to meet the photographer and came away deeply impressed by both her singular dedication to photography and her personality. Even as I only heard her words with delay and in translation, her soft spoken and thoughtful demeanor left a deep impression on me.

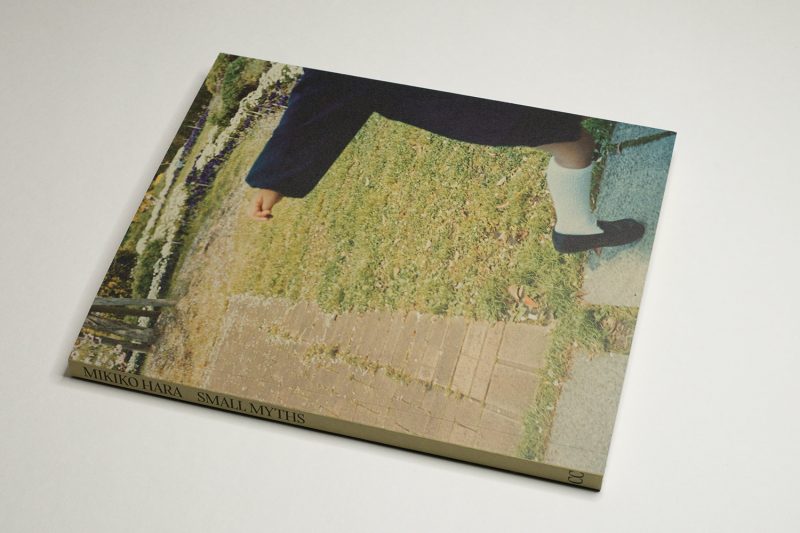

It is tempting to file away Hara as a street photographer, especially when one looks at the work the Getty has in its collection. Ever since I met the artist, I realized that such a filing essentially misses the point of her work. To begin with, the pictures that easily fall into the category of street photography are not remotely as interesting as the rest of her work. A recent book, Small Myths, that collects work made over the course of two and a half decades, makes this very clear. The book presents the street photographs in the context of a large number of other photographs, many of them taken within the confines of the photographer’s own home.

Hara’s photographs are the outcomes of brief encounters (of course, this much is true for a lot of photography), but it’s encounters in which the artist’s presence is essential (this is not). For a short moment, a subject and herself get to share the same space, a space that goes beyond the physical one. Unlike the regular street-photography crowd, Hara is not photographing as an outsider, someone who records what is in front of her camera for the sake of demonstrating her artistic wit. Hara also doesn’t view her subjects or subject matter merely as raw material for her pictures.

Instead, this artist experiences the richness of a moment that might bypass other people completely — a richness beyond visuals, a richness of full of feeling. The pressing of the camera’s shutter is but an attempt to capture a fraction of it in a photograph. The overall richness of the world that is experienced in this manner only unfolds once a viewer sees it not in a single image, but rather in a collection such as the one presented in the book.

This has very little, if anything, in common with the way standard street photography operates along the lines of the so-called decisive moment. With their often helter-skelter compositions (remember, the camera has no viewfinder), Hara’s photographs simply do not fit into Henri Cartier-Bresson’s idea that form and content have to be perfectly resolved. Here, form isn’t necessarily resolved (at least not in an orthodox sense); and yet Hara demonstrates what can be gained from ditching what more often than not reduces photography down to a petty craft.

There are worlds between those who hunt for their pictures with expensive Leicas and this Japanese photographer with her old-timey tool that doesn’t even remotely come close to what today would be considered a good camera. Street photographers are interested in demonstrating their ability to shape the world into a picture. Mikiko Hara is interested in the world.

Where a viewer will encounter a demonstration of skill in the former, in the latter, they get to be immersed in the actual richness of the world, a richness that is based on connecting with things and people, on being in and with the world — and not on extracting pictures.

Being in and with the world means being open to its magic. Every moment might reveal such magic at any given time. Small Myths is filled with it, whether it’s a small child being basked in light in a domestic space, the interior of a fridge with a cake topped with strawberries promising some future enjoyment, dirty dishes in a sink, a woman on the phone in front of a bright blue wall, or whatever else.

In Nan Goldin’s The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, one of the key images is a picture of an embrace. The photograph shows a woman’s back, with a muscular male arm exerting a very strong, violent grip around her (it’s entitled The Hug). Small Myths contains the same kind of photograph, except here, there is nothing violent about the embrace (it’s the fourth picture in the slide show for the book). The man’s hand rests on the woman’s behind, who, in turn, seems relaxed. Both pictures demonstrates their photographers’ very different visions, and I really like both photographs.

In light of the above, I think Small Myths is an absolutely essential release. The book showcases Mikiko Hara’s sensitivity and genius in ways that I have not seen in other books. It’s interesting that Chose Commune have been consistently publishing books with Japanese photographers that are very, very good (unlike the rest of their program, which I find mostly underwhelming).

Even as I don’t want to see Japanese photography as distinct from photography made elsewhere (this would be a form of exoticizing or othering), there can be different sensitivities at play when Japanese artists face the world with their cameras. It is these sensitivities that Western photographers and audiences can learn a lot from.

You can make good photographs if you follow ideas such as the decisive moment (and thus turn your picture taking into an exercise of artistic genius). But you can also forget about the strictness and inflexibility of many of those ideas and embrace looser approaches that prevent the camera from becoming the barrier between photographer and the rest of the world that it often is.

Honestly, even if you don’t care about any of what I wrote above, you still want to get yourself a copy of Small Myths: the book is filled with incredible photographs.

Very highly recommended.

Small Myths; photographs and short texts by Mikiko Hara; 104 pages; Chose Commune; 2022

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing to my Patreon. There, you will find exclusive articles, videos, and audio guides about the world of the photobook and more.

Much like journalism, photography criticism involves a huge investment of time and resources. When you become a subscriber, you not only get access to more of my work. You will also help me produce it (including the free content on this site).

Thank you for your support!