One of my biggest photography related pet peeves is most artists’ and critics’ unwillingness or inability to take images made outside of the very narrow confines of photoland seriously. If you listened only to the chatter inside photoland I think you’d be very surprised once you visited Instagram or got exposed to any of the many other ways in which photographs have become a prominent feature of everyday life. Photographs are now routinely used to communicate a large variety of often incredibly mundane messages, messages that despite their being mundane still have a power that, let’s face it, most artists can only dream of in their own work.

Of course, you dismiss the richness of photography outside of the photoland cloisters at your own risk. This fact was demonstrated last year by Anika Meier‘s exhibition Virtual Normality, which focused on a number of young female artists in dialogue with not only everyday ways of sharing pictures but also with societal restrictions and taboos that still play out in the larger public sphere (even though in principle, Instagram is not a public sphere, much like Facebook it de facto has become one).

Along these lines, Talia Chetrit‘s photographs also stand in dialogue with both public and private pictures, the former ones being those widely and openly seen and discussed, the latter privately seen and if discussed then only in private settings (or in news reports about sexting blackmail, say). As already noted above, I have long been fascinated by these two spheres, by their interaction or overlap, and by the (intellectual and actual) prudishness with which most of photoland approaches that overlap.

In her essay in Showcaller, the newly released catalog of Chetrit’s work, Sahra Motalebi spells this overlap out as follows: “Any of our phones holds private directories of our workplaces, family, enemies, parties, items for sale online, other artist’s work, but also, possibly, of our genitalia, and those of others.” This simple statement has considerable power. In this particular context, I believe it allows for a fuller understanding and appreciation of what is on view in the catalog, namely many photographs that in possibly less photographically competent ways might exist in many people’s phones.

Placed into the context of photoland, there exist a variety of artists that are referenced in the photographs, ranging from Barbara Probst to Janice Guy to Izima Kaoru (the latter in the for me least interesting pictures in the book, older work in which Chetrit poses as a murder victim). There would be considerable insight gained from just that context, especially in light of the ideas around which Virtual Normality centered and which are explained much better in that catalog than I could do it here.

But as already noted, there also is that escape into the larger world of photographs, an escape that might not exist for much longer, given that photoland — much like capitalism itself — tends to annex (and then commodify) everything that successfully escapes its cloisters’ walls eventually. This escape here centers on female sexuality and agency, and the latter of inevitably is tethered to aspects of power (again, see Virtual Normality for other examples).

If, as still is the case, men live by different rules concerning their representation — regardless of whether or not they’re the ones taking their own picture, then demanding that the very same rights should also apply for every other member of society is a political — feminist — act, which just happens to manifest itself partly through what I suppose would be called sexually explicit photographs.

This brings to mind another reference, Jemima Stehli who explored some of these aspects in different ways (e.g. see this interview). But it also brings to mind Aliaa Magda Elmahdy, who became a feminist icon in her native Egypt during the brief Arab Spring and who now lives in Sweden (with Egypt having become a military dictatorship yet again; see this article).

It’s crazy that thirty years after Barbara Kruger produced her seminal image (Untitled) Your Body is a Battleground, it is just as relevant today (if not even more). That shouldn’t be the case. But it is. And with photographs having become a means of communicating at least somewhat publicly for much larger segments of society, the struggle has become ever more visible, ever more pressing, one image on Instagram that supposedly violates their “community guidelines” at a time.

I personally believe that photographs on their own are completely meaningless. Photographs only acquire meaning in context. Their meaning is then negotiated by those perceiving them while the acts of making/selecting and then placing them acts serve as catalysts. In other words, photographs are made by people, and they’re made for people: photography is a form of politics. Photoland — especially the “art” section with its gigantic, buffoonish pretenses — is awfully good at concealing this basic fact.

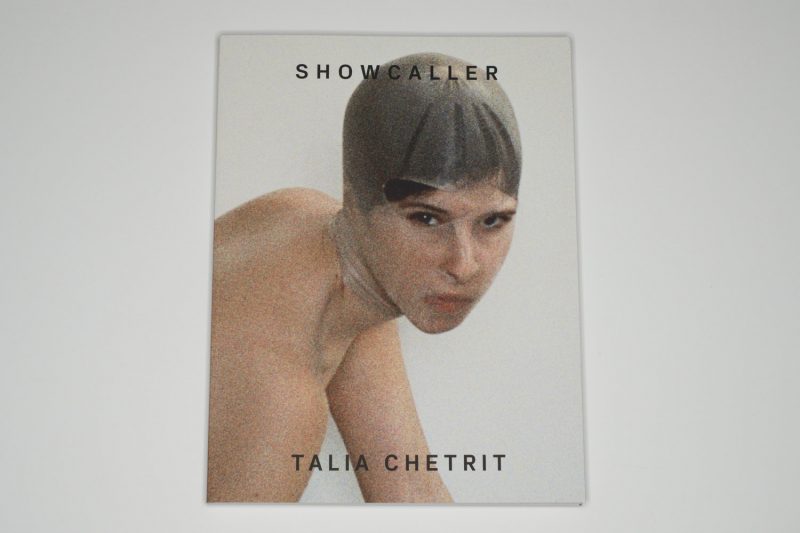

Sexuality and agency, power (or its denial thereof), observation — all of these aspects are touched upon in Talia Chetrit’s Showcaller, and all of them are of extreme relevance today. The catalog thus focuses on the politics of looking, a politics that plays itself out daily on millions of small screens. Much like Virtual Normality, it elevates what runs the risk of becoming atomized on those small screens to a larger stage.

Showcaller; photographs by Talia Chetrit; essays by Sahra Motalebi, Ruba Katrib, Moritz Wesseler; MACK; 2019

(not rated)

Ratings explained here.