A few years ago, I lived in Pittsburgh, PA, a city trying to get over the fact that while there were much better days in the past, those are unlikely to come back. My apartment was somewhere close to the line that divided an area considered attractive to one seen as anything but. The line wasn’t completely invisible, as it is in so many American cities where you simply know where you belong. There was a public-transportation route cutting through, to be used by buses only and usually deserted, a rude, brutal conglomerate of concrete. Even the buses offered a bit of a divide, with its regular buses, stopping everywhere, and the express ones that zoomed right to the university areas.

A couple of years after I moved there, the city decided to tear down a large public-housing building that was deemed to be an eye sore, to be problematic. The people living there were promised alternative housing, which might or might not have arrived. In any case, they had to go. And then Whole Foods moved in or rather, it literally crossed that dividing line, building a supermarket, daring those who thought better of venturing across the line to do so, provided they wanted, say, their tiny piece of “gourmet” cheese for $15. Other corporations followed, including a chain book shop (I don’t quite remember the name any longer, they’re all the same anyway), and a chain thrift-store that sold to used dresses for $20.

Essentially the better off had chipped way a little at the territory of those who weren’t that, those who still had to worry about what to spend money on. Far beyond the dividing line, things didn’t change that much, despite the city’s best efforts to lure in, for example, artists, offering them houses to buy for little more than a wet hand shake. There was a fair amount of violence going on, and people peddled drugs. Artists did move in, and some of them moved back out again.

I haven’t been back to Pittsburgh since I left, so I have no idea what happened to those areas. But this story seems to be fairly typical of the country as a whole. Now, I only need to drive down a few miles, and I’m in Holyoke, MA, a city that makes Pittsburgh look like a tremendous success story. Or I could drive down to Hartford, CT. In fact, wherever I drive there always is some city that has not only seen better days, but that essentially is trying to put a brave face on the simple fact that there is if not no hope then very little for it.

Not too long ago, you were able to find this kind of situation in New York City, right in Manhattan. You wouldn’t know necessarily this from visiting the strip mall for the wealthy the island has become of late. But you might be aware of it, given that so much of its transformation is tied to the arts, tied to it providing the fuel for the arts, some of it anyway.

Maybe this is too convenient an argument to make, and just like any convenient argument it’s essentially false. But that energy coiled up in the city, in Manhattan, fueled the arts as much as did the existence of incredibly cheap (albeit often ridiculously dangerous) housing. Just to digress a little: Now if that is correct, then we might as well find an alternative term for New Formalism: Gentrification Art. Because, you know, if so little matters to you in your life, if there is so little actual risk other than maybe missing an opening, then why would anything matter in your art? Why not just produce visual fluff?

Anyway, I’m not sure I personally would have lived on, say, Avenue B at a time when the founders of Sonic Youth lived there, or Ken Schles, the photographer.

There’s this general problem with looking back to a time that in retrospect looks so alluring because of some of its symptoms. All that art coming out of Manhattan in those days – that’s really a symptom, and I don’t mean this in any bad way. I love a lot of the stuff. Bad Moon Rising is awesome in ways that contemporary music simply doesn’t seem to aspire to any longer. But it’s still a symptom, the result of a sickness of the municipal body.

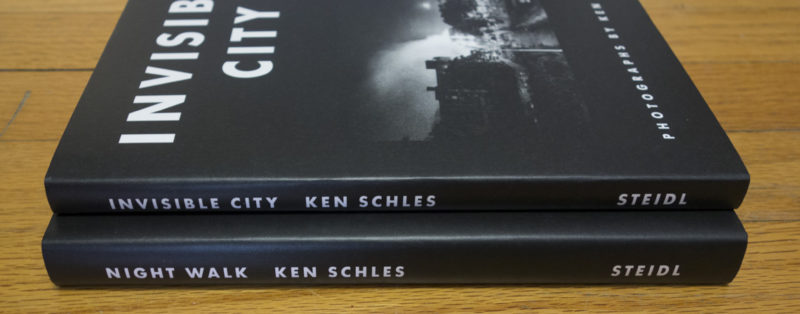

So there is that push and pull here that one needs to be aware of. The story often sounds great, but at the same time, its beauty is grounded in circumstances that are anything but beautiful. I think this applies to Schles’ Invisible City and Night Walk

. Invisible City is a re-release of its original 1988 incarnation, which has long been hard to come by (for those with limited funds). Night Walk, in contrast, was compiled from material that didn’t make it into the 1988 book, material that has now been given a life in book form. So you can treat these books as companions. They certainly speak of the same thing, even though there is quite a bit of a difference in their focus.

Photographically, both book provide copious amounts of photographic references. In City, for example, there is a photograph of a kid pointing a gun at you, clearly echoing William Klein’s New York book. With their bleak and harsh black-and-white treatments, occasionally using considerable blur, the books also echo Japanese photography from around the Provoke era. Of course, many of these references have since been picked up by a younger generation of artists.

I got a bit of a weakness for this kind of aesthetic, even though I realize that it’s also a bit easy. I mean, anything will look kinda cool if you just boost the contrast in b/w and show some serious grain. It’s a bit like visual punk rock: as long as its really loud and fast, and you cram 20 songs into 30 minutes, you got yourself some punk. But it’s one thing to do that, and another thing to be the Ramones.

My first reaction after looking through both Invisible City and Night Walk was that I like the latter better. A lot better. The thing about City is that while it contains some pretty great photographs, the overall edit is a mixed bag. And the added quotes from Kafka, Borges, Orwell, Beaudrillard, and others really make it feel as if someone was trying a bit too hard. It feels very self-conscious. In contrast, Walk sings.

The reality is that as we age, we get a little wiser. We don’t really have to try so hard any longer. And I think Invisible City and Night Walk make a pretty great case for just that. Walk feels expansive in ways that City feels restrictive. There’s a specificity to City that doesn’t allow its viewers to enter it under any conditions other than the one it lays out. Walk, in contrast, both echoes the times and circumstances under which the photographs were made, but also our times and circumstances, the things we do (or don’t do), the things we share (and don’t share).

Seen that way, Night Walk does what it needs to be doing, given our cities’ lives: it references the past as much as the present and the future. It doesn’t glorify or condemn outright. It’s really only punk in visual form. To stay with music analogies, it has much more in common with latter-day Swans than with 1985 Sonic Youth.

Invisible City; photographs by Ken Schles; 80 pages; Steidl; 2014

Rating: Photography 3, Book Concept 3, Edit 2, Production 5 – Overall 3.4

Night Walk; photographs by Ken Schles; 162 pages; Steidl; 2014

Rating: Photography 3, Book Concept 4, Edit 4, Production 5 – Overall 3.9

Ratings explained here.