One of the challenges with words is that they will shade how you view photographs. While you can in fact use words with photographs, making them an integral part of the work, I think for the most parts words are being added to photographs after the fact, to serve as a statement to go alongside them or maybe as a slightly longer text to provide some context.

Depending on whether you see your photographs as the work or not — or maybe whether you want your audience to focus only on the photographs — a problem arises: the words might draw a lot of attention to themselves or to the story that they convey, a story that maybe would not reveal itself in quite this fashion in the pictures. Words, after all, function differently that pictures: they’re specific in ways that pictures are not.

On the other hand, it’s not clear whether an insistence on the primacy of photographs really helps to work with the full breadth of possibilities the medium has to offer. In part, that insistence on the primacy of photographs derives from the medium’s practitioners’ earliest attempts to establish their craft as, well, a form of art. Conventions were copied and adopted from other media (mostly painting) that undercut photography and vast parts of its potential.

In the end, if text has not been made an integral part of the work a photographic body of work still has to convey its intended purpose in a clear and self-contained fashion. However, even though many pieces of text added on later have as much utility as, say, a blurb a publisher might produce to sell a novel, there are cases where the text might add an essential part of the experience.

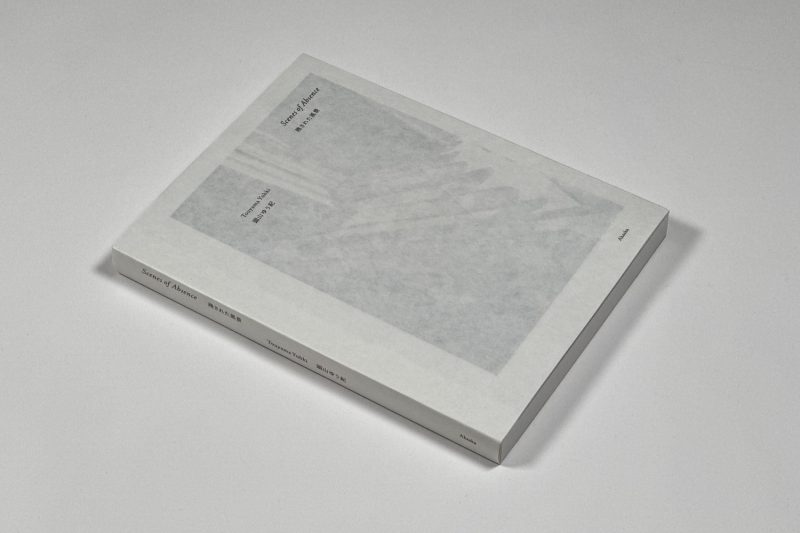

This certainly is the case for Touyama Yuhki‘s Scenes of Absence (頭山ゆう紀 — 残された風景; please note that I’m following the Japanese convention used on the book’s cover: family name followed by given name). If you were to ignore the text at the end, you would not only miss insight into how the work was made and what it alludes to. You would also miss one of the most heart-breaking pieces of text written by a photographer I’ve read in a while.

The text begins with the photographer’s grandmother announcing a cancer diagnosis that at age 92. Given her age and possibly also given the restrictions posed by the then ongoing Covid pandemic, the decision is being made not to pursue treatment. Instead, Touyama moves in with her grandmother and takes on the role as a home carer (at least initially supported through regular visits by a nurse and doctor).

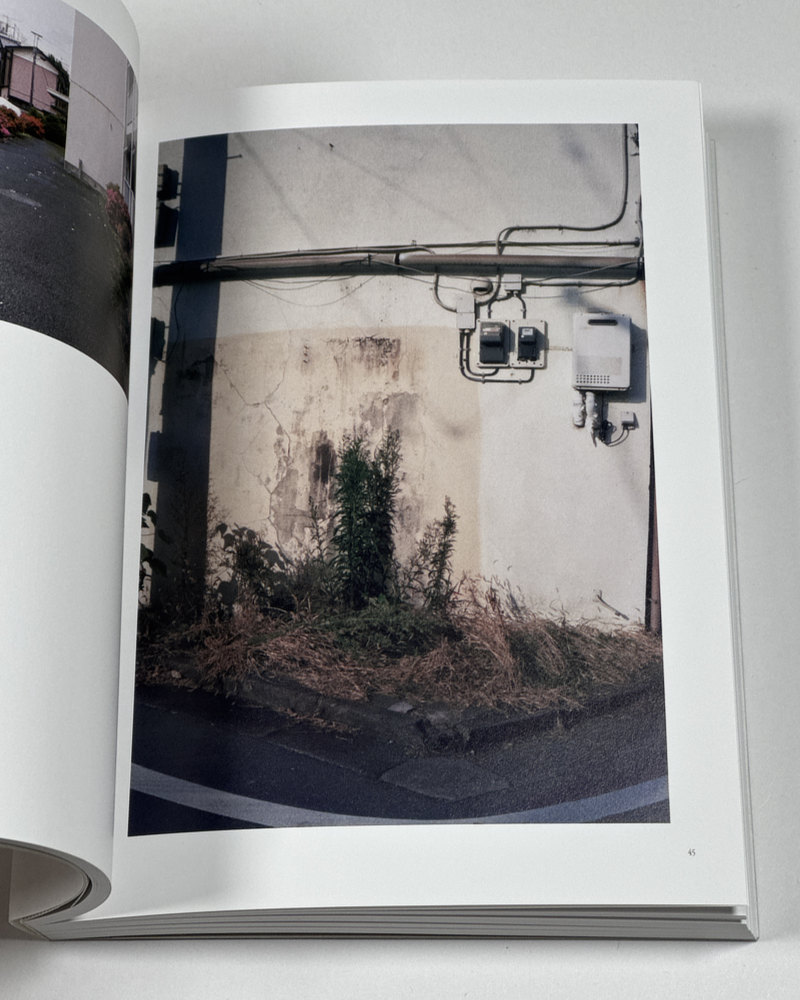

Contrary to the initial assessment (“she has only three months at best”), the grandmother beats medical odds and survives for over a year. While taking care of her grandmother’s needs, Touyama takes photographs when she finds the time: the outside world seen from the inside or scenes encountered while being out on errands. As I suppose anyone can imagine, the long-term role of a caregiver is taking an increasing toll on her, though.

“My time as a caregiver had not gone well,” Touyama writes. The final three paragraphs of her text are absolutely heartbreaking. In it, the photographer voices her frustrations with relatives who abandoned her with the task at hand (“my father’s inability to take care of my grandmother because ‘men just can’t do that'”) and with herself (“I should have shown her more kindness”).

Once the grandmother has passed away, Touyama Yuhki is left to live with, in her own words, “endless regret and questions. Although I read lots of articles and books on caregiving, in actual practice I couldn’t keep up with what I learned.” The photographs are almost entirely devoid of her inner turmoil; and it is precisely this fact that makes the combination of the text and the photographs so poignant.

After reading the text, I found myself looking through the book time and again, trying to pinpoint some of what I had read in a photograph. Was there a way to see a sign of frustration, of trying to make her grandmother’s time more bearable? In the end, I am convinced that what I saw I only saw because I either wanted to see it or because I imagined that were I in this particular position I would maybe take such a photograph.

But that’s merely what words will do: they will affect us to see photographs in a specific fashion. It’s important not to lose sight of what matters, though: the first and foremost task at hand is to acknowledge the photographer’s hurt. Then, and only then, can one move on to imagining being in her place.

Scenes of Absence might appear to be a specific book about a specific situation (a Japanese woman taking care of her dying grandmother), but it’s really not. Caregiving is a task performed all over the world. All over the world it is gendered, whether it’s taking care of young children or of dying relatives. That father who decreed that “men just can’t do that” could be almost any man, even if the verbiage, of course, might vary. More often than not it falls on women to do the caring.

Seen that way, the absence in the title of the book also points at a larger absence in our societies: An almost complete absence of meaningful conversations around the duty of taking care of someone.

“It’s fine,” Ishiuchi Miyako, the grand dame of Japanese photography, says in a long conversation with Touyama Yuhki (I’m quoting from the machine translation; there is a short video with English subtitles that you want to watch), “as long as you keep taking pictures and don’t give up,” referring to photography’s ability to give solace to those who are in need of it. While Ishiuchi’s words specifically refer to a photographers, I think they extend outwards to viewers as well.

Things will be fine, we might conclude about any of the topics portrayed through photographs, as long as you keep looking at picture and don’t give up on looking the world, understanding what it ails, and on then making it a better place.

Recommended.

Scenes of Absence; photographs and text by Touyama Yuhki; 176 pages; Akaaka Art Publishing; 2024

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing to my Patreon. There, you will find exclusive articles, videos, and audio guides about the world of the photobook and more. For those curious, there now is the possibility of a trial membership for seven days.

Much like journalism, photography criticism involves a huge investment of time and resources. When you become a subscriber, you not only get access to more of my work. You will also help me produce it (including the free content on this site).

Thank you for your support!