Davide Degano‘s Romanzo Meticcio begins with reproductions from a 1938 pamphlet or magazine. I don’t speak Italian, but many of the words are familiar enough even in their somewhat different spellings. Razza bears similarity to Rasse from German (race in English). Il principio della razza seems clear enough (the year is 1938 when Italy was under fascist rule), and I bastardi certainly is, especially given the range of photographs used to illustrate the idea.

And it keeps going this way for two more pages; I can’t help but move a little faster through these pages. It’s not that I can’t believe that almost 90 years ago this type of material was so widely believed and assimilated; it’s the fact that the Vice President of the country I live in essentially repeats it on a regular basis on TV.

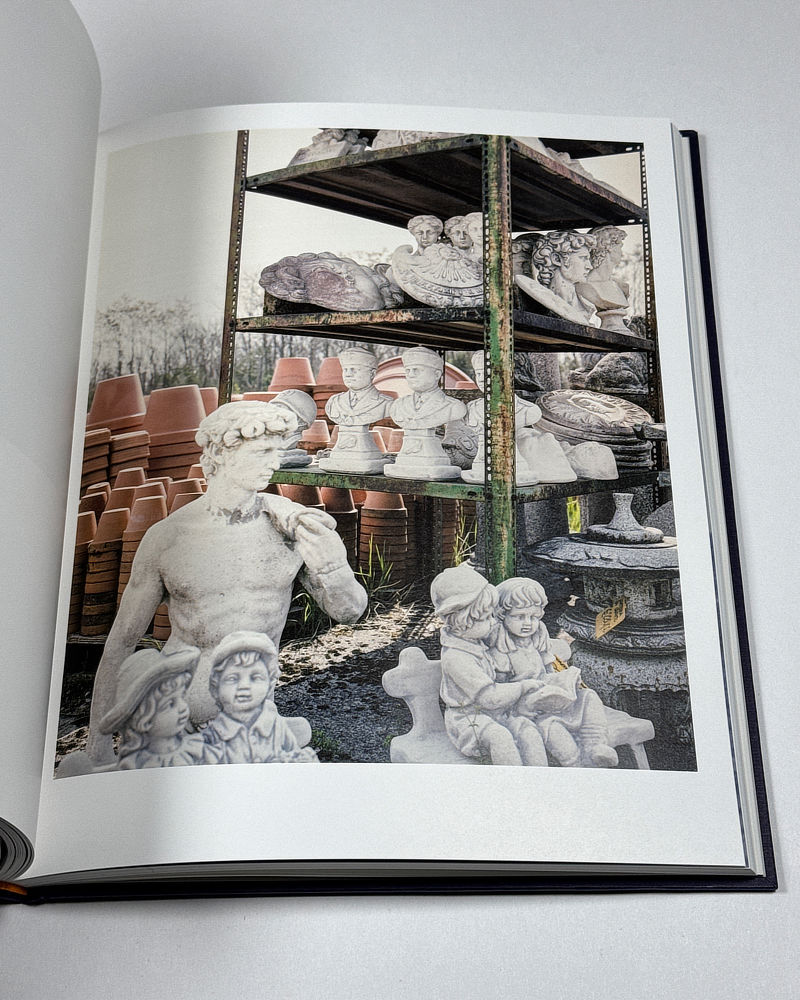

Italy’s curse is that it occupies the territories from which the Roman Empire sprang many hundreds of years ago. It’s difficult to go anywhere there without stumbling upon some of its ruins.

I don’t know how many generations have passed since it crumbled into dust; but it’s probably exactly those many generations that allow for the idealization that we can now observe not just in Italy (some of the most powerful people in Silicon Valley are very fond of that Empire even as it is obvious that they know very little about it).

Mussolini, the original fascist, built the foundation of his rule on his country’s distant and presumed glorious past. Never mind that the Romans were actually very liberal with their ideas of citizenship. A number of Roman emperors actually weren’t Italian. Trajan and Hadrian hailed from what is now Spain. Septimius Severus was born in Northern Africa and appeared to have had roots there. Marcus Julius Philippus is commonly known as Philip the Arab.

As one of the texts in the back of Romanzo Meticcio explains, Trajan, Hadrian, Septimus Severus, and Marcus Julius Philippus would have to apply for Italian citizenship if they lived today: “To this day,” Davide Valeri explains, “Italian citizenship is considered a right for those with the same blood, while it is a prize or a gift for all the others. Non-descendants of Italians have to earn it by proving how deserving they are to be accepted by Italian society.” (emphases in the original)

Up until fairly recently, the situation was exactly the same in the country I was born in, Germany. Many thousands of young people, born to so-called guest workers from Turkey and elsewhere, did not have German passports even though they had never lived in a another country. Based on what the texts in the book tell me, this is still the situation in Italy, meaning that many of the people in the photographs are finding themselves in this situation.

Race and citizenship ultimately are merely constructs to divide people, regardless of whether that division is ideological or bureaucratic (let’s not argue over whether you can have one without the other).

The inclusion of the historical text right at the beginning of Romanzo Meticcio is heavy handed. It’s likely that a viewer would have figured out what’s going on by looking at the photographs first, to then be told some of the background. Alas, we don’t live in times that ask for a more, let’s say, polite treatment of the matter.

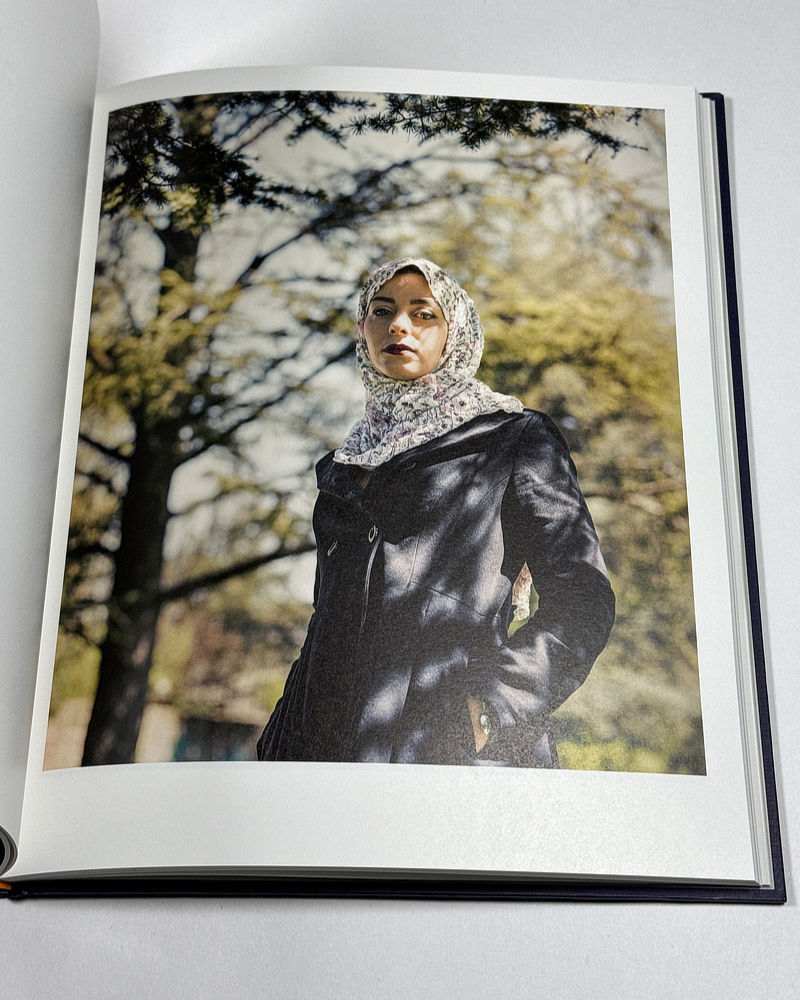

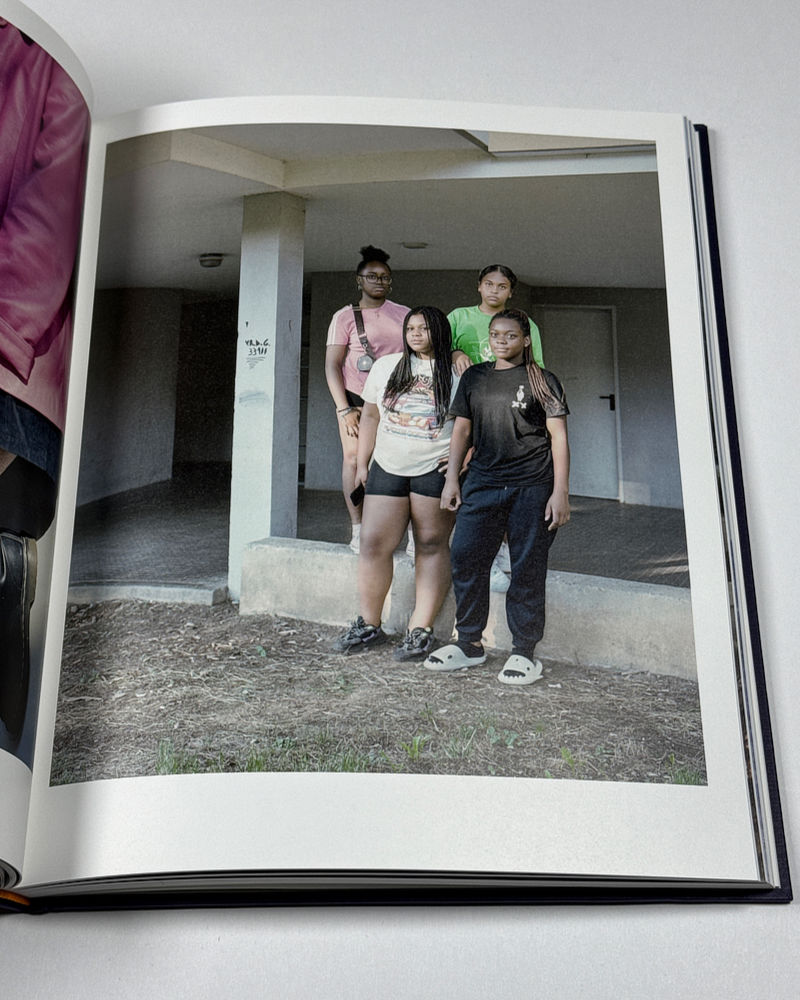

Furthermore, the texts charges the photographs before the viewer has seen them. And it is exactly that fact that lends them such potency, in particular the many portraits of people, most of them young, who one suspects belong to the group that would have to prove that they’re “deserving […] to be accepted by Italian society”.

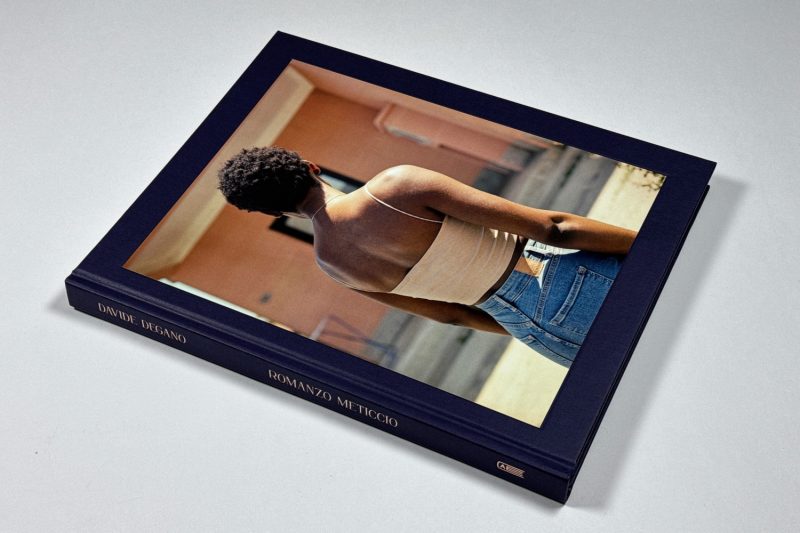

Romanzo Meticcio unfolds through a combination of photographs of Italy’s lived environment and portraits. We could have a discussion over whether all of the photographs of people are in fact portraits. But that would take us into the neutered photoland territory where ultimately nothing matters other than photographic dogma. So let’s not do that. If we define a photographic portrait as a picture that conveys something about a person’s spirit, we’re good.

Because that’s what this ultimately is all about — the book as much as the struggle we’re now witnessing in our collective sphere: is one person’s spirit of equal value as another person’s, regardless of how different the two people might be?

As far as I can tell, typically discussions start out from abstract concepts and then try to move to the people affected by them. However, it’s very much worthwhile to do it the other way around: to start from basic principles. Doing it this way places the burden of proof on the Italian government to justify why some people have to earn their right of citizenship even though they’re born in the exact same country as the others who don’t.

Romanzo Meticcio clearly is a book of and for our times. Unlike many other contemporary photobooks, in which their makers try very hard to avoid making an open statement, here it’s very clear. And it works not only because of Degano’s clear convictions but also because of the quality of the photographs.

The photographs are seductive and delicate, even when there is someone in a portrait who channels his inner Mussolini. Don’t get me wrong, I don’t have any illusions about people who vote for fascists. But I also know what denying another person’s humanity can lead to. Still, at any given moment, the focus cannot be on trying to understand fascist voters while so many other people are literally fearing for their lives.

Romanzo Meticcio was published with a relatively modest edition size — 300 copies, meaning (possibly) that you might have to act fast to get yours (assuming you want one). The book is a marvelous achievement by Davide Degano, a new addition to the Italian photography scene.

Recommended.

Romanzo Meticcio; photographs by Davide Degano; texts by Davide Degano, David Forgacs, Igiaba Scego, Davide Valeri; 160 pages; Artphilein; 2024

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing to my Patreon. There, you will find exclusive articles, videos, and audio guides about the world of the photobook and more. For those curious, there now is the possibility of a trial membership for seven days.

Much like journalism, photography criticism involves a huge investment of time and resources. When you become a subscriber, you not only get access to more of my work. You will also help me produce it (including the free content on this site).

Thank you for your support!