Publishing photobooks is a labour intensive and almost completely thankless business: at best, you might see your company’s name listed in one of the many, many shortlists (that often aren’t so short at all). If a prize is given, it’s the photographer who gets it, regardless of the fact that while it’s her or his photographs, it might actually be other people who made the book what it is, starting with, well, the publisher. The reality is that good publishers know how a photobook can succeed, whereas many photographers don’t.

The best way to understand photobook publishers is through looking at their books. With many publishing houses, if the name on the spine is mentioned, one instantly has a good idea of what a book might look like or, roughly, what work an artist might have produced. For example, everybody knows what a Steidl book looks like and what kind of photography is likely to be found therein. In this particular example, there is a dedication to the craft of printing that I can appreciate regardless of whether or not I like every book made in Göttingen (I don’t) or whether I think every book needs to come with heavy layers of ink (nope).

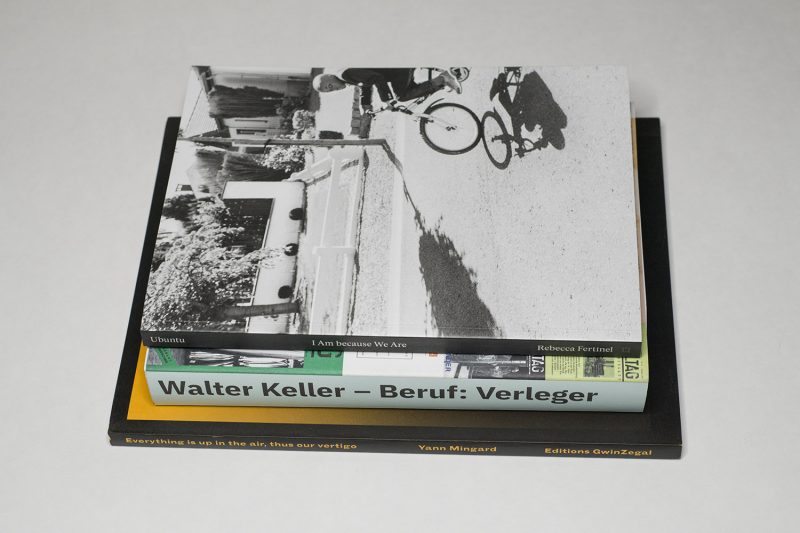

Walter Keller might not be a household name in photoland, even though many of the books he produced and championed clearly are. In the world of photobook making, he’s a legend. Whether it’s Richard Billingham’s Ray’s a Laugh, Michael Schmidt’s Ein-Heit, Merry Alpern’s Dirty Windows, Roni Horn’s You Are the Weather, Gilles Peress’ Farewell to Bosnia, Nan Goldin’s I’ll Be Your Mirror, or Here Is New York — A Democracy of Photographs (the book that would ultimately wreck the publishing house) — these are just some of the books made by Walter Keller, some in conjunction with Fotomuseum Winterthur, an institution he co-founded.

A new book, Walter Keller — Beruf: Verleger (Walter Keller – Profession: Publisher), now dives into the man’s life and work (note that at this time, the book only appears to be available in German). Keller wanted to publish early on in his life, and he wanted to work with photographs. His earliest product was a pamphlet that later turned into a more refined magazine named Der Alltag (The Everyday). Besides Keller, the magazine involved a number of people who would go on to play serious roles in the world of photography, such as Urs Stahel (one of the driving forces behind the book) or Patrick Frey (whose own company published it).

There are ample examples of spreads from Der Alltag, just as there are spreads from the many books Keller ended up producing. In addition, there are numerous essays and conversations about the man, who comes across as incredibly driven and visionary, with the flip side of not the best sense of business and a certain degree of myopia. The book also dives into Keller’s womanizing, devoting a whole essay to it, which I found a little bizarre. What insight is gained from the essay is unclear to me.

One aspect that I enjoyed about Walter Keller — Beruf: Verleger is to discover artists whose books I hadn’t heard of before. So far, my own biggest discovery is Marianne Müller’s truly extraordinary A Part of My Life, which is still available for next to nothing everywhere online. If that book were published today, I think it would be widely discussed: it’s such strong work that does not betray its age at all (the photographs were all made in the early to mid 199s). It’s not included in the recent How We See: Photobooks by Women, so there’s a book by a well known publisher that somehow ended up being more or less forgotten.

Walter Keller — Beruf: Verleger; editors: Urs Stahel, Miriam Wiesel; texts by Theres Abbt, Bice Curiger, Regina Decoppet, Nan Goldin, Martin Heller, Martin Jaeggi, Liz Jobey, Friedrich Meschede, Michael Rutschky, Joachim Sieber, Andreas Spillmann, Urs Stahel, Nikolaus Wyss;432 pages; Edition Patrick Frey; 2019

(not rated)

Rebecca Fertinel‘s Ubuntu (I Am because We Are) employs a few tricks to elevate pretty standard documentary-style photographs into a interesting book. It speaks of a sense of community in ways that don’t feel quite as restricted as an ordinary documentary photobook would be. To begin with, the text that provides the (basic) background of the pictures is hidden underneath the flap of the back cover. There are no title page or table of contents. The photograph on the front of the book continues inside, and this device is used for all horizontal images: one half can be seen on one side of a page, the other half on the reverse.

Such an approach runs counter photobook orthodoxy (which is most pronounced in the United States). But the key here is that while it’s a photobook, it’s not necessarily a collection of photographs any longer, with some added text. This is not a new idea, but one that said orthodoxy just can’t wrap its head around: the book is the entity to be considered and not any one (or a few) of the photographs contained therein. Consequently, the various celebrations contained in the book blend into one another, whether it’s a wedding, a birthday, a funeral — it’s all one community coming together to celebrate life through being a community.

It’s not just some community. The title already contains a hint. Ubuntu is often translated as I am because we are, “but is often used in a more philosophical sense to mean ‘the belief in a universal bond of sharing that connects all humanity.'” (sadly, if you Google just the word “Ubuntu”, you’ll learn all about some computer operating system). The term originates in Africa, and so do Fertinel’s subjects. There are a few hints in the photographs betraying the locale, and the text at the end of the book confirms what an attentive viewer is able to puzzle together: the portrayed form part of the Congolese community in Belgium (background).

This is a book for our times. Not only does it show the beauty of a group of people that, I’m sure, is not very widely known at all. It also very strongly hints at the value and beauty of the idea of community, the idea of belonging together and of living with and for each other — and not against each other, as seems to have become the modus operandi pushed by neofascists and populists all over the world and amplified on social media. The fact that Ubuntu is as much a concept originating out of Africa as humans themselves holds special relevance: there is much that can be learned from those who for too long have been at the receiving end of colonial violence.

And it is really only the form of the book itself that conveys this message as it refuses to reveal time and again the kinds of specifics that anyone based in a Western tradition is used to expecting. With the idea of community in mind even the treatment of the photographs, the wrapping of the horizontal ones around the pages, makes sense: it’s all about the overall result, about making a viewer feel the larger whole instead of them getting each and every one in an atomic fashion.

Ubuntu (I Am because We Are); photographs by Rebecca Fertinel; texts by Hans Theys, Rebecca Fertinel; 164 pages; Lecturis; 2019

Rating: Photography 3, Book Concept 5, Edit 3, Production 5 – Overall 4.0

On a surface level, Yann Mingard‘s Everything is up in the air, thus our vertigo has nothing to do with Ubuntu (I Am because We are). It’s highly conceptual — a stark contrast to the documentary approach used by Fertinel. But in both cases, the larger idea is being approached through photography’s strange muteness: pictures show, but they don’t tell — because by construction they can’t. In this particular case, the Swiss artist presents a number of seemingly separate topics that, together, address the larger issue of the Anthropocene.

In each case, a grouping of images (presented without captions — some very basic factual captions are hidden in the book’s front flap) is being accompanied by some short, factual text. The images might be photographs by Mingard, or they might be screen grabs of videos, or reproductions of documents or paintings. The text itself then reveals the very basic underlying topic, which explains everything and nothing: everything because the viewer/reader gets an understanding of what s/he might be looking at, and nothing because abstract or long-term processes cannot really be visualized, let alone understood. They just are.

I think it’s the book form that’s most conducive to allowing for a project like this to shine. The photographs are beautiful and incredibly competently made, but I’m not sure on a wall, with some text next to it, they’d work as well. Maybe this is me being impatient with reading wall text; but maybe this is also me being a little bit tired of looking at large prints in expensive frames in some white-wall environment (that you might have to pay an admission fee for) attempting to speak of some larger drama: I’m just unable to look past the production value and the sheer artifice of it all. But I haven’t seen the exhibition the book is based on, so maybe I got it all wrong.

Regardless, the challenge of conceptual work always is that it runs the risk of coming across as too complicated, as too cerebral, as too much made for that small crowd of curators that really loves conceptual photography. I think the only antidote possible is for the photographs to be beautiful and not too clinical. With its inclusion of a relative wide variety of materials, Everything is up in the air, thus our vertigo succeeds. I particularly like the beginning of the book that compares Turner paintings with screenshots of air pollution in China. The colours themselves are visceral, and the artifice in the image sources makes for an unexpected comparison.

Much to his credit, in his “straight” photographs, Mingard resists the temptation to stylize the work too much. A lot of the photographs are very dark or use a black background, but there are enough others that avoid the risk of the style becoming a gimmick. Taken together, however cerebral the idea of the Anthropocene might be, its consequences are all around us, most notably in the form of climate change. There is much for each and everyone of us at stake here. Hopefully, books such as Everything is up in the air, thus our vertigo can help raise awareness of what we’re dealing with.

Everything is up in the air, thus our vertigo; images by Yann Mingard; texts by Frédéric Moser; 144 pages; Editions GwinZegal; 2018

Rating: Photography 3.5, Book Concept 4, Edit 3, Production 3.5 – Overall 3.6

Ratings explained here.