After I received Nicholas Albrecht‘s One, No One, and One Hundred Thousand, I looked through it. Then I looked again, and again, and I liked what I saw. Still, I had no clue what this was actually supposed to tell me (thankfully, I didn’t discover the blurb on the book’s back until much later – do yourself a favour: don’t read it). When teaching photography, the question “what is this about?” usually arises, one of those inevitable constants. It’s a great and necessary question in many cases, as much as it is pretty dreadful as well.

Why does everything always have to be about something?

I smell a flower, and I enjoy that – what the hell is that supposed to be about?

(If any of my current and/or future students read this: don’t even think about using what I’m writing here as an excuse for not being able to talk about your own work.)

But photographs aren’t flowers, they’re photographs. They can act like flowers in their own specific ways, causing chemical reactions in our heads that we treat as if they were connected to something in the external world, and that might or might not be the case. Who is to say?

That is, to repeat myself yet again, the beauty of photography: it’s often not quite clear to what extent what we think or feel when we see a photograph comes from what’s actually in the picture. There is all this other stuff we carry with us, which, inevitably, will have us see photographs in our own – unique – ways; and you can’t have photography without that.

There can’t be photography if you think it’s about projecting something onto a blank slate. This is a big problem for photography, of course, one of the most technical, geeky, and seemingly overtly descriptive forms of art.

In this particular case, the back of the book gives you some information concerning the “about.” I don’t think it was a very good idea to print that on the back. I suppose when you want to sell a book that’s oblique you need to give people pointers. But still… The back story and the little explanation simply don’t matter. Ultimately, these pictures work very well on their own, creating a world that is more than just a little bit unsettling.

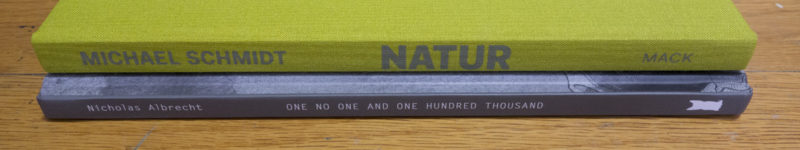

One, No One, and One Hundred Thousand; photographs by Nicholas Albrecht; text by John Marlovitz; 84 pages; Schilt; 2014

Rating: Photography 4, Book Concept 3.5, Edit 3, Production 2.5 – Overall 3.4

Just a few days after being awarded the Prix Pictet photography prize, Michael Schmidt died in a Berlin hospital following a long battle with illness. At around the same time, Natur was being published, a book that he had been working on while being sick. There remains much to be said about this particular artist. I believe a reassessment of his work is overdue to understand his artistic accomplishments more fully and deeply – moving away from the Waffenruhe centric focus, towards a wider understanding of how this artist made everything he touched truly his own, while opening up new ways of seeing. This new, most recent book can help us understand Schmidt’s legacy.

The photographs in Natur were taken between 1987 and 1997 and edited and compiled this year. As the title indicates, they deal with nature, or maybe more properly with our own understanding or ideas of nature. Most of Schmidt’s work was done in his version of black and white, as is the case here, a seemingly vast stretch of grey tones, with black and white being mostly absent. A Michael Schmidt photograph always looks and feels like one in part because of that. It’s almost as if the image had a weight itself, a weight not necessarily related to feelings of being heavy or light, but instead to having a presence.

If you go to Berlin, you can still find spots that look like Schmidt might have photographed there. But while it’s somewhat straightforward to see those spots, it’s impossible to conjure the weight and presence that an actual photograph by this artist would produce. This is, after all, why we look at photographs: not to see what we can see, but to feel the photographer’s presence, to experience the photographer assert her/himself in the scene, onto the scene.

Natur easily references work done by other artists, and it contains echos of Schmidt’s earlier work (how could it not?). It also showcases some of the visual strategies Schmidt employed, which include repetition and/or just very slightly modified vantage points. But descriptions are hardly able to bring the experience of looking through the book any closer.

Instead, imagine sitting on a bench somewhere, and you hear a curious little and somewhat peculiar tune, a tune which after a while you can’t get out of your head any longer. You’re not quite sure why it appeals to you so much, but you don’t want it to stop.

Natur; photographs by Michael Schmidt; 104 pages; MACK; 2014

Rating: Photography 4.5, Book Concept 4, Edit 3, Production 4 – Overall 4.0

Ratings explained here.