Exhibition catalogues typically are that, collections of pictures with lots of often borderline unreadable text written by academics and/or curators. As I have attempted to argue on this site before, it needn’t be that way. Not that there’s anything wrong with the idea of the old-fashioned catalogue. But chances are if you haven’t first seen the exhibition, the catalogue will leave you feel wanting more.

Lee Miller, published at the occasion of an exhibition at an exhibition at Vienna’s Albertina demonstrates how the experience of the catalogue can be vastly improved (the exhibition is going to travel to the NSU Art Museum in Fort Lauderdale later this year). Of course, there are many well-known photographs covering this still underappreciated photographer’s career, ranging from her involvement in the surrealist movement until her work during and right at the end of World War 2. But crucially, a lot of much lesser well-known images are also presented. What is more, there are reproductions of contact sheets and “outtakes” (many of which I had never seen before).

In addition, a set of very well written and informative essays brings considerable depth to the viewer’s/reader’s understanding of what s/he is looking at. As a matter of fact, I was left wanting more (which doesn’t really happen that often especially with exhibition catalogues). The only things I would not have missed are the two “visual essays” included in the book. While I can see how you’d want to make an exhibition/book as interesting as possible, thing is if the quality of the central work is very high, anything that doesn’t reach the same level will just stick out as falling short.

The concern about the added visual essays aside, Lee Miller is a must have for those interested in the history of photography, and in particular those interested in this photographer who still deserves a lot more attention.

Lee Miller; photographs Lee Miller; visual essays by Anna Artaker, Tatiana Lecomte; essays by Astrid Mahler, Anna Hanreich, Ute Wrocklage, Elissa Mailänder, Walter Moser; 160 pages; Hatje Cantz; 2015

(unrated)

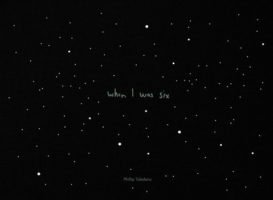

To review Phillip Toledano‘s When I was Six is a bit of a thankless task, unless, of course, you find nothing wrong with it. If you do, however, then, well, that basically makes you a heartless bastard. I suppose someone has to do it. This is not to say that it’s a bad book. Don’t get me wrong, it’s pretty good. But it also emotionally manipulates its viewers in ways that are entirely unnecessary, and that’s my problem with it.

Around 40 years ago, Toledano’s young sister died in an accident, and she wasn’t spoken of again. Literally. Many years later, the photographer found some possessions left behind in boxes, stashed away by his grieving mother. Photographs of some of those possessions comprise part of When I was Six. It’s hard to imagine what one must feel upon coming across such boxes. It’s hard enough to do so in the case of someone recently deceased. But someone else who died decades earlier and was never spoken of again?

Another large set of photographs in the book are images made to look like astronomical ones, mirroring the photographer’s intense interest in the science at the time his sister died. This is where this gets iffy for me, since as adults I don’t think we can attempt to understand the intellectually limited, but emotionally very much evolved world of young children. That’s a step too far for photography. Any attempt to do so, as in the book, for me reduces the pain a six-year old might have felt to, well, some sort of obviously metaphorical approximation that in reality can’t even come close to the real thing.

Toledano adds this all together using his own words, which, tersely, describe (and explain) what is on view in the book. Again, per se there is nothing wrong with these words, were it not for the fact that without all the pictures that would have been the book. But the combination of all of this attempts to cover every base, not allowing for the viewer to insert herself or himself in any other way than the prescribed one.

And that’s really my problem with the book. Photographs are strongest when they hint at something intensely emotional. But for them to do it best, you will have to allow them to do it, without prescribing the viewer’s experience. After all, in all likelihood as viewers we share the experiences of loss and grief, however much details might differ.

When I Was Six; photographs and text by Phillip Toledano; 78 pages; Dewi Lewis; 2015

Rating: Photography 3, Book Concept 2, Edit 3, Production 5 – Overall 3.3

At the end of World War 2, millions of Germans were forcibly expelled from land they had been living on for generations, the last of many such acts of violence during the conflagration that destroyed vast parts of Europe and laid the foundation for a new order of the continent, large parts of which are still with us. In a sense, Stalin’s ruthless redrawing of borders solved many of the problems Europe had been dealing with for a long time. Many countries that previously had sported considerable ethnic minorities now were much more uniform. But of course, for those forced to leave their homes it was a disaster, ending at worst in a frozen death on some road west, and at best as a non-ethnic minority in one’s own country.

Rosemarie Zens was born in a small town called Bad Polzin in 1945. Bad Polzin now is called Połczyn-Zdrój, and it’s part of Poland. Zens isn’t Polish, though, she is German — as a result of her mother packing up and leaving, much like many other ethnic Germans. And she went back to the land that she never got to grow up in, to see… what? What is there to be seen? To be experienced? I’m not sure anyone could comprehend. So what then is there to photograph? Well, everything and nothing.

The Sea Remembers collects what I called everything and nothing. In particular, there are photographs by Zens, many of them landscapes. In addition, there are what look like fragments of vernacular/archival photographs, which we might assume to come from the author’s family’s albums. And then there is text written by Zens, text that describes what can be describe, but that leaves everything else open, to be explored (most of it comes at the very end, after the photographs were allowed to do what they can do).

What do you lose when you lose something you don’t even really know? And how can you re-find it, assuming it’s even possible? As the viewer of the book, you’re left hanging: There is no easy answer provided. Which is, I’d argue, the only way to go about this. You’ll have to come back and look again.

The Sea Remembers; photographs and text by Rosemarie Zens; 144 pages; Kehrer; 2015

Rating: Photography 3, Book Concept 4, Edit 3, Production 3 – Overall 3.3

Ratings explained here.