If, as I pointed out last week, there are plenty of photobooks that don’t have — and need — a narrative, there are all those that do. Narrative-driven books currently are all the rage, to the point of the idea of “narrative” almost having become a bit of a fad. But this development shouldn’t get into the way of us enjoying those books that work particularly well, such as Laia Abril‘s Lobismuller.

One of the “problems” with narrative-driven books is that they tempt the reviewer to give it all away, to, in other words, talk about the story, thus (possibly) marring the possible viewers’ experience. In addition, by construction there is a literalness to photography that often extends (or actually is being extended) to our discourse around the medium, a literalness that, frankly, I’m at war with. So I’ll try to refrain from that here. Just briefly, the book centers on a Spanish serial killer who lived in the mid-1800s. There are many additional details that vastly complicate this basic story and that reveal themselves beautifully through the book.

Usually, good photography (or photobooks) is (are) good not because they’re literal, but even though they’re literal. At least, that’s what I enjoy about photography, when it’s used well: as a viewer, you rub against everything that “despite” the photographer’s best intentions is incommunicable. I’m using quotes around “despite,” because when you make a photobook, you need to be very aware of this aspect — if not, at times, make sure that you’re not ruining this very fact, in particular if you’re making a narrative-driven book. You have to resist to provide too much information, to, in other words, place the bread crumbs the viewer is supposed to follow too narrowly together.

In Lobismuller, Abril and frequent collaborator Ramon Pez employ their considerable skills, using the by now well-established tools available for the makers of narrative-driven books, such as a variety of source materials and layouts, production choices (different paper types and sizes), plus the addition of text in various places. I realize my description might make their work seem formulaic, but I don’t mean it that way. After all, if you produce your usual gallery-show-on-paper, that’s no less formulaic than adding facsimile document inserts in books.

The main question really should not be whether any of the choices used to make a (any!) photobook are new or overused or whatever else the criticism might be, but rather whether they work, whether, in other words, they help the photobook (but not viewer’s ideology) in question. Approached from that angle, the many choices that went into the making of this particular book work very well. Even though there is a main narrative, Abril and Pez actually present more like a weave of narratives, where more cerebral strands mix with decidedly emotional ones. In particular, the full-bleed section starting roughly after the middle of the book works tremendously well.

Anyone interested in narrative-driven photobooks is well advised to pay close attention to the books made by Laia Abril and Ramon Pez. Lobismuller provides a very good entry point to their thinking. And anyone else is in for a visual treat, with the book showcasing some of the things you can do with pictures and text in photobook form.

Lobismuller; images and text by Laia Abril; 192 pages; RM; 2017

Rating: Photography 3.5, Book Concept 5.0, Edit 3.0, Production 4.0 – Overall 3.9

“I believe,” I wrote in March this year, “that an exploration of ‘the social and political landscape of the United States’ is essentially useless if it systematically excludes the most dominant group, the group whose economic and political power shapes the country.” I still believe that. An investigation of the wealthy, of the incredibly privileged, of those unlikely to suffer from any of the rather basic problems 99% of the US population have to deal with all the time — such an investigation must be part of the world of photography attempting to tackle the state of the world we’re living in.

Sage Sohier‘s Witness to Beauty is, well, that: a look at privilege, privilege in more than one way. First and foremost, though, it’s an extended portrait of the photographer’s mother, a former model who at some stage was photographed by the likes of Richard Avedon, Irving Penn, or Philippe Halsman, a woman whose face was featured on the covers of magazines such as LIFE (January 26, 1948) or CHARM (December 1947; CHARM billed itself as “The Magazine for the Business Girl”). The book makes all of that abundantly clear, laying out photograph after photograph before the title page, a flurry of pictures taken by famous photographers plus an ample amount of family photographs, one more celebratory than the other.

This ought to have been a bold decision to make by Sohier: after all, the viewers would see all the photographs by Avedon et al. first. But it works, because there really can’t be a competition here, given those photographs were the distant past, whereas the other ones, Sohier’s, show the more immediate past and present. In addition, the former clearly inform the latter in this indirect way. I have no way of knowing this given my life’s circumstances are so very different. But whatever I imagine what growing up as this woman’s daughter must have been like, it can’t have been easy (it is not for nothing that the photographer’s essay in the very back is entitled “In Beauty’s Shadow”).

While Sohier makes her mother the central figure of her work, she also includes a cast of other characters, most prominently her sister and herself. Photographs always are a fiction. So who knows who contributed how much to what I’m picking up. But the mother and her display of regal beauty come across as a bit insincere, as if the facade were just about to crack, as if someone knows how to act very well but can’t help but overact just a tad. The roles of the photographer and her sister also differ, with the former displayed as being in on the spectacle — unlike the latter. My read, of course, is based solely on the pictures, on not personally knowing any of the portrayed. But my read also makes this book intriguing, given that too perfect a picture (pardon the pun) would easily make the whole affair very trite.

And then there also is the privilege, the almost complete absence of any of the more fundamental problems that so many other people have to deal with. This also makes this book intriguing to me, because it irritates me a bit. Through the various devices I discussed earlier, as a viewer I’m being given some sort of access to this world. This is not just in the way that photographs always deceive into showing more than they do. In addition, I feel I’m being held at more than just an arm’s length here. So I don’t know what to make of this world that ultimately I have no access to, other than the one I’m being granted (yes, that would be the word) here.

Witness to Beauty; images and text by Sage Sohier; text by Marvin Heiferman; 108 pages; Kehrer; 2016

Rating: Photography 3.5, Book Concept 3.5, Edit 3.0, Production 4.0 – Overall 3.6

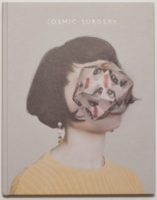

There’s a small industry of artists who will take photographs and physically manipulate them, whether by embroidering, punching holes into them to shine lights through, or whatever else. Alma Haser is one of these artists. Her Cosmic Surgery essentially is based on an iterative process that starts out with a portraits, taken by Haser, and that then moves through an origami-style stage, to eventually end with a photograph of the slightly sculpturesque contraption produced this way. As someone who enjoys when photography is being taken a step further I enjoy the idea. That said, in almost all of these kinds of approaches, a grouping of such pictures for me ends up as being a lot less than just a single one.

How do you make a photobook out of these pictures? A simple catalog, gallery-show-on-paper style, would probably be dreadfully boring (your mileage might vary). That can’t be it. Obviously, you’d want to make a book that incorporates the very process with which the photographs were made. I’m using “obviously” here probably in part because I have already seen the book, plus I’d love to think I would have come up with the same idea (whether that would have indeed been the case I’ll — possibly thankfully — never find out). So you’d want to make a book with pop-up components, given that these incorporate the basic idea. In theory, that’s a great idea, in practice, it vastly complicates the production of the book, because the pop-up components can’t be added by machines. They require hand work.

And so it was done: there is a book. The folks at Stanley James Press collaborated with Haser on the making/production of the book. The design and production choices adopted for the book are simply brilliant, arriving at what I think is the best possible realization of a photobook out of the source material. The design itself is elegant, simple, and a bit playful, while neatly avoiding doing too much, which would have turned the whole thing into something a bit too cute (or maybe twee). The production also wasn’t overdone: there aren’t a dozen pop-ups in the book — that would possibly not only have been too costly, it would ruin the whole idea through needless repetition.

So It’s really the perfect book for this body of work, a huge surprise for me when I received it in the mail.

Cosmic Surgery; photographs by Alma Haser; text by Piers Bizony; Alma Haser; 2016

Rating: Photography 3.0, Book Concept 5.0, Edit 3.0, Production 5.0 – Overall 3.7

Ratings explained here.