With big-name publishers commanding so much attention, the world of photobook publishing is more of a struggle for smaller publishers. Their pockets aren’t as deep, meaning they can’t offset the losses from a book that doesn’t sell against the income from many other books they print. Getting the word out there is harder, too. Often, you have the same person playing a wide range of roles at the same time: editor, designer, publisher, PR person, packaging and shipping department, etc. So I decided to focus this week’s set of photobook reviews on books made by small publishers.

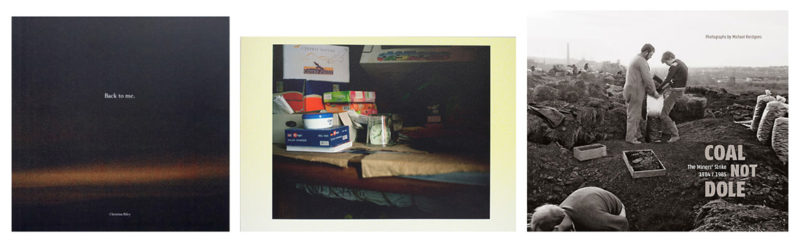

I wasn’t going to review Back to Me by Christina Riley after I learned it was sold out. It’s not that I don’t like the book – quite on the contrary. But if a book is sold out, and people have no chance of buying it… However, there now is going to be a second edition, which gives those who either didn’t get to buy it or those who haven’t even seen it before to get their own copy.

The world of mental illness is hermetically sealed from a camera’s probing eye. Whatever is going on in your head might manifest itself in whatever ways in your expression, in what you do or don’t do; but the thinking and feeling and worrying and being excited and being drained is unphotographable. You can, however, photograph anyway, even if it’s “just” because you feel you have to. Out of whatever set of photographs you create might then emerge the story in ways that might seem almost miraculous. In a nutshell, that is the background of Back to Me.

For those who have never been depressed the world of depression is and will forever be completely inaccessible, and it’s the same for any other mental trouble one might be afflicted with. In other words, as a viewer you can’t look at a set of photographs and expect to see or even understand what mental illness is like. It’s just not possible. But there are connections that we all can tap into, given that our world of emotions is complex. While some emotions might be vastly amplified in the case of mental illness, we all know what it’s like to be sad or heart-broken or happy or excited.

And that is why Back to Me works so well. It doesn’t convey the photographer’s anguish and feelings directly; instead, it makes us feel with her, and it gives us an idea of the intensity of suffering, an intensity that most of us will never have to experience. Photographed with an old digital camera, the pictures contain the added element of rawness through the low quality of the sensor, driving the point home that a photographer is sharing something that is unsharable. But it’s being shared regardless, and out of that gesture derives the power of this initially unassuming book.

Wytske van Keulen‘s Sous Cloche is a double portrait of two people – Saskia and Andrez – who each decided to essentially live in solitude somewhere in the French Pyrenees. At some stage of their lives, both of them were confronted with a trigger that had them move away from everything. Saskia was diagnosed with cancer and did not want to subject herself to the standard medical treatments. Andrez lost his wife and unborn child. People have run away from what they had for lesser reasons; but these two certainly underwent traumatic shocks.

Presented literally side by side in the book, Saskia and Andrez never knew each other. Pictures on the left-hand and right-hand side of a spread are from Saskia’s and Andrez’s life, respectively. This juxtaposition makes for a very interesting effect, since their stories are made to merge, even though they are also kept apart.

We like to think of ourselves as unique individuals, but in reality we share a fair amount with other people, even when it comes to such extreme decisions in life as those taken by the protagonists of the book.

Just like Back to Me, Sous Cloche is an initially unassuming book, which reveals its beauty only upon closer engagement with it. It features text written by the photographer, descriptions of events or meetings with either Saskia or Andrez.

Saskia didn’t make it. She lost her struggle with cancer. Andrez still lives up somewhere in the Pyrenees. There are demons you just can’t run away from.

The subtitle of Michael Kerstgens’ Coal Not Dole – The Miners’ Strike 1984/85 – might make it look as if we were dealing with a book that looks back to a specific, historical event. And in a sense, it is. The strike involved a brutal fight against a government – Margaret Thatcher’s – that ultimately prevailed. As Kerstgens notes in the book “It was the birth of deregulation, the chief tenets of which were laid down in the 1980s by conservatives such as Margaret Thatcher, US President Ronald Reagan, and German Chancellor Helmut Kohl, followed by Tony Blair’s New Labour and Gerhard Schröder’s Social Democracy in the 1990s.”

The book is, in other words, showing us one particular – and noteworthy – facet of a development that has landed us in the, well, mess we’re in now, with jobs being rare and badly paid, and profits being the yard stick used to measure whether the economy is doing well or not. The book smartly makes this connection very clear, because the photographer went back to the places and people he photographed three decades later, most prominently among them a man named Spud Marshall.

Should photography be political? Should artists have an opinion? Well, who is to say? But it actually doesn’t hurt to occasionally come across a book like Coal Not Dole that reminds us of what photographs can do when there is an agenda, when someone decides to take a side, instead of waffling around conflicting points of view.

We might not have to agree with what we are being presented here. But it certainly makes for a livelier engagement. And it’s so refreshing to see a bit of passion, a passion that reminds us of a time when it seemed photographers were a little bit less afraid to offend someone, and jobs and the social structures around them were much more meaningful than they are now.

Back to Me; photographs and text by Christina Riley; 52 pages; Straylight; 2014 (both editions)

Rating: Photography 4, Book Concept 4, Edit 3, Production 3 – Overall 3.6

Sous Cloche; photographs and text by Wytske van Keulen; 80 pages; Kominek; 2014

Rating: Photography 3, Book Concept 4.5, Edit 3, Production 3 – Overall 3.4

Coal Not Dole; photographs and text by Michael Kerstgens; 132 pages; Peperoni Books; 2014

Rating: Photography 4, Book Concept 3, Edit 3, Production 4 – Overall 3.6

Ratings explained here.