In late March, an essay I wrote for Hyperallergic about Contemporary Photography’s Capitalist Realism was published. In the piece, I attempt to look at a fairly significant portion of contemporary photography from a different angle, investigating its position vis-à-vis capitalism itself, and placing used strategies into an actually well-known framework from art history. The term Capitalist Realism isn’t new. It was used in similar, yet somewhat different ways in the past. My own use differs a bit from previous incarnations, in that here, in the realm of contemporary photography, it is entirely devoid of irony.

Capitalist Realism almost always demands a somewhat critical position. Socialist Realism, in contrast, isn’t critical at all. Instead, its goal is openly and admittedly propagandistic, presenting a happy, pleasant world that in reality does not exist (because its underlying political/economical system is incapable and/or unwilling of producing it). But while Socialism of the Stalinist (and related) kind(s) is unwilling to deal with criticism, Capitalism does the exact opposite. In fact, if you look at the recent history of art, it’s almost as if art dealing in whatever ways with the system is only good if it is critical of that very system.

As a consequence, large parts of contemporary photography are at least on the surface openly critical of, let’s say, pollution or social injustice, and those photographs are then sold to very wealthy collectors in upscale galleries and/or auction houses, the same people who represent the system the most. This is a contradiction that I think needs to be discussed more. And it might just point to what I centered my essay on, namely that the criticism in large parts of contemporary photography actually mostly supports the system, without resulting in any meaningful change.

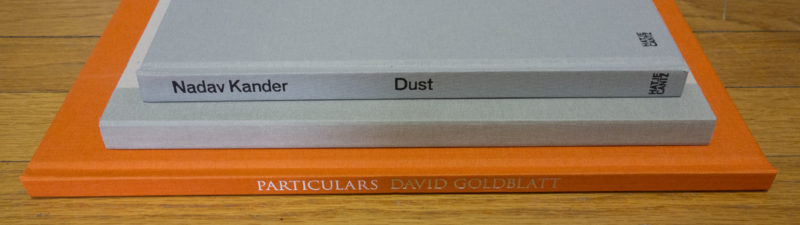

I focused my essay on two recent photobooks, one by Tor Seidel, entitled The Dubai. Seidel’s book is easy to understand in the context of Capitalism Realism – it really is mostly a visual celebration of one of the icons of Capitalism, the city of Dubai. The other book I discussed is Nadav Kander‘s Dust

. This seemingly is a tougher nut to crack, given that unlike The Dubai it so much more critical of what it depicts, the remains of previously closed military/research sites in the former Soviet Union.

Kander’s photographs employ the aesthetics this artist has been known for. The vistas are usually sweeping, with a level of stylization that leaves everything a bit more lifeless than it maybe should be. How much to stylize such photographs is possibly the most important conundrum photographers such as Kander (but also Gursky, Burtynsky, et al.) have to face. Take things too far, and you got something that looks like like a painting, but actually too much like a painting: too removed to convincingly make the viewer think that the maker actually cares about anything else other than his technical skills (Gursky literally zoomed out of scenes until he was left with utterly pointless photographs of the planet’s oceans).

Here, Kander struggles with this problem, and he finds himself at both sides of this crucial divide. Some photographs are potent and moving, because they make the foolish pomposity behind the depicted scenes resonate with the viewer’s emotions. Other photographs are just too removed, too stylized, to achieve that goal, leaving the viewer with essentially exercises in how to make photographs of vast landscapes.

So Dust ultimately fails to make me care. I’d love to care about what I’m presented, but there aren’t enough hooks to lure me in. It is all a bit too precious, a bit too concerned with photographic form, a bit too, well, calculated.

Dust; photographs by Nadav Kander; essays by Will Self, Nadav Kander; 120 pages; Hatje Cantz; 2014

Rating: Photography 2.5, Book Concept 3, Edit 3, Production 5 – Overall 3.3

Jo Metson Scott’s The Grey Line is an odd book to include in these reviews, for a variety of reasons. For a start, it was published in 2013, which doesn’t exactly make it a too recent book. But then, unlike bread, phoobooks can be just as fresh a year (or more) after they were published.

What’s more, the book might not even strictly be a photobook for some people, given it places so much emphasis on text. Without the text, it won’t make much sense to someone merely being interested in looking at its pictures. As far as I am concerned, that’s not necessarily a problem. I’m perfectly happy with the photographs in a book only doing some of the lifting, as long as the text doesn’t just become a crutch for an artist unable to take the pictures s/he needs. Here, that’s clearly not the case. The text supplements the pictures, telling large parts of a story that photographs cannot convey.

And somewhat oddly, The Grey Line also is a photobook that is critical of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq that moves beyond the widely shared modus operandi of most work produced around them, where the lives of soldiers will be presented in – often – excruciating detail, yet the wars themselves, and especially the more than dubious rationale behind them, essentially don’t exist. Unlike during the Vietnam War, say, soldiers now can expect a lot more sympathy from those covering what we now call “conflict.” Unlike during the Vietnam War, the government doesn’t have to worry about being held accountable for what looks to many people as at least one extremely foolish adventure any longer.

A facsimile sketchbook, The Grey Line presents photographs and, crucially, the words of a number of soldiers who refused further service during the wars in Iraq or Afghanistan. Their reasons vary in detail, but they agree – to paraphrase a bit liberally – that these wars, either including some of their consequences or the reasoning behind them, were not what they signed up for. This hardly is a new problem, but maybe a bit surprisingly, it’s not something widely discussed.

If, for example, you find yourself appalled by your peers just for the fun of it scooping brain matter out of the skull of a man shot essentially willy-nilly, wouldn’t that qualify as a good enough reason to say “I’ve had enough of this”? (Not making this up, an episode like this is included in the book) Now, if that is no good reason to refuse further service, what would be a reason? At what stage does society allow a soldier to follow her or his conscience? This is an important question, especially for those societies that are democratic. And this is what this book centers on.

I’m tempted to think the book is not so much about the individuals discussed therein, as it is about us, about our willingness (or maybe also ability) to question authority, especially when said authority is leading us into what looks like an abyss. Any nation waging war will inevitably face this problem, given that war tends to bring out the worst in people. To merely celebrate the bravery or heroism won’t suffice. Instead, it will ignore the costs of war, and it will make future wars only more likely.

The Grey Line; photographs by Jo Metson Scott; texts by Jo Metson Scott and others; 122 pages; Dewi Lewis; 2013

Rating: Photography 3, Book Concept 4, Edit 3, Production 3.5 – Overall 3.4

The announcement of the (then upcoming) (re-)release of David Goldblatt‘s Particulars had me excited. Here was a body of work based on an extremely simply idea, which made it incredibly hard to photograph it well (this is how photography tends to work): details of the human body, produced from people encountered somewhere (thus not studio work, which would be something entirely different).

I don’t know how his happened, but I somehow convinced myself that the book would be not only a modest affair, it would in fact be quite small, maybe around the dimensions used by Gerry Johansson for most of his photographs. Have I been teaching too long? Have I spent too much time thinking about the best form for a photographic body of work? Possibly. What I clearly wasn’t prepared for was to receive a book in the mail that is in fact anything but modest and intimate. At 13.75″ (35cm) wide and high, it is, well, huge (Amazon lists it as 20″ by 20″, but, you know, that is exaggerated). Wha’ happened?

It might feel wrong to dwell on the fact that these pictures would have required a much smaller, a much more modest affair of a book. But still, it’s quite crucial. After all, here we have photographs that pay the utmost attention to the ways people shape, contort their bodies, many of them focusing on hands or feet. And that discovery needs to be shared with the viewers. The viewers ought to be given a chance to almost feel they are the ones discovering what is there to be seen, not the photographer. Instead, the photographs are so large that the energy contained therein dissipates.

(I’m going to factor the size of the book into “Book Concept.” “Production” really only refers to the technical production value of the book, which, Steidl being Steidl, is pretty much impeccable.)

There are some killer photographs in this book. It’s somewhat obvious that photography is all about looking carefully, but it’s a lot less obvious what this actually means. One of the problems with so much photography produced these days is that it replaces the careful looking with a hyper-caffeinated gawking. Now that’s fine for a little entertainment, but just like the caffeine will wear off, so will the pictures (and you’re left with, well, not much). Goldblatt is too smart a photographer to allow this to happen.

Especially the best photographs in Particulars what what can be gained from an attentiveness to the world that knows it needs to balance a desire for the perfect photographic form with the resulting pictures containing more than just that.

Particulars; photographs by David Goldblatt; 64 pages; Steidl; 2014

Rating: Photography 4, Book Concept 1.5, Edit 2.5, Production 5 – Overall 3.4

Ratings explained here.