Of late, the idea of the female gaze — as opposed to the male gaze — has been gaining traction. The concept of the male gaze was introduced in 1975 by Laura Mulvey in her essay Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema. Its core idea is that of a man looking at a woman and of the female body being objectified in such ways that men are empowered: women are being treated as objects of male (predatorial) desire. That type of looking at women is made the dominant visual approach for everybody, men and women alike.

Part of the reason why I prefer thinking about the male gaze this way is not only because it kills the whataboutism that inevitably will be produced by many male photographers (“But what about [female photographer]’s work?”), it also focuses on the aspect of the skewed power dynamics involved.

For me, this aspect of power is crucial in a variety of ways. To begin with, I don’t subscribe to the idea that any group of people ought to have power over other people for reasons other than possibly democratic (and thus correctable) ones.

Furthermore, the idea of a dominant way of looking defeats one of the core ideas of art, namely of allowing a viewer to experience the world in a way s/he might not have considered before. If, in other words, as a man I only get to the see the world through the eyes of other men (the male gaze), then what is the point of looking at all? Having lived on this planet for decades I know quite well what that looks like. I personally don’t need to have my ideas of what the world looks like confirmed. Instead, I want art to challenge me, making me see the world in ways that I’m unfamiliar with. How else would I be able to learn something about myself and others?

Consequently, I do believe that men — and not just women — should have an interest in getting the male gaze challenged and punctured: it’s not just that the visual oppression of women — some of whom might be our mothers, sisters, daughters, partners, etc. — should be unacceptable to us. It’s also that the male gaze stands in the way of art reaching its full potential.

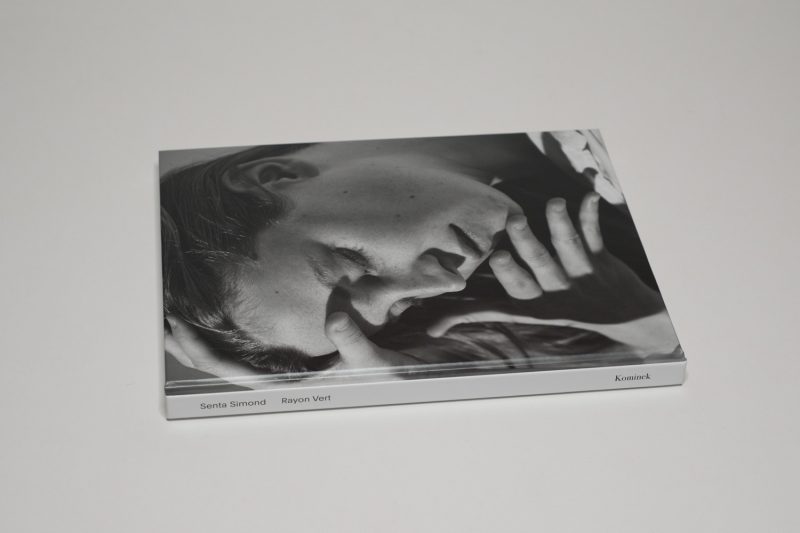

As I noted above, thankfully counter models are now being produced more and more, allowing our collective visual vocabulary to expand while helping shift the still very skewed power dynamics between the sexes. One of the most impressive and captivating recent examples is Senta Simond‘s Rayon Vert, a collection of portraits of young women.

What makes these photographs so thrilling is the sheer variety of approaches used by the artist. For each model, considerable work appears to have gone into figuring out how to portray her. Poses vary considerably, as do the angles with which the women were approached. There are colour pictures and black and white ones, there are tight crops and wide ones — in the hands of a less gifted photographer, this variety would have been a recipe for disaster. But Simond made it work. It’s very impressive.

What is more, the form of book itself helps elevate the work even further. There are blank spreads between the portraits plus slight variations in image placements and sizes. As a result, the viewer has no choice but to see each photograph on its own terms. It’s no gallery of portraits that invites possible comparisons. Instead, it’s a collection of individual portraits that, however, powerfully add up to a larger whole: here is part of the world beyond the male gaze, and it’s magical.

Highly recommended.

Rayon Vert; photographs by Senta Simond; 100 pages; Kominek Bücher; 2018

Rating: Photography 5.0, Book Concept 5.0, Edit 5.0, Production 5.0 – Overall 5.0

Ratings explained here.