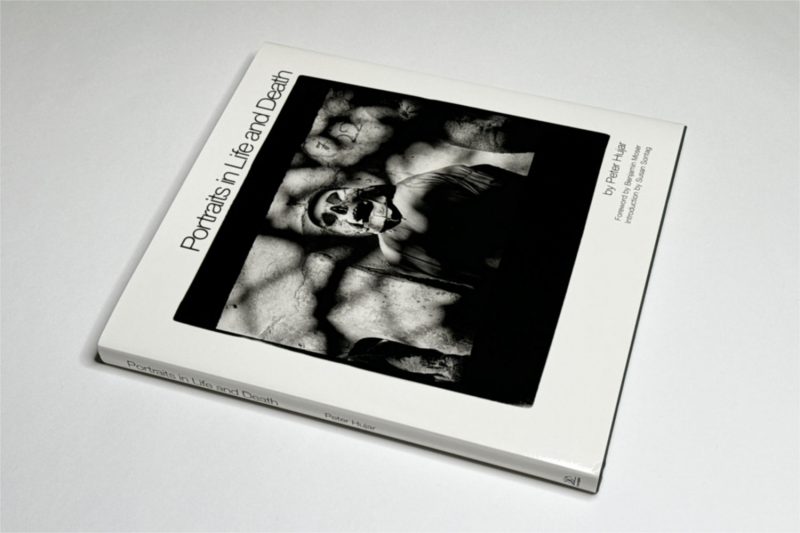

There a numerous reasons why Peter Hujar is not as widely known as anyone who is familiar with his work would assume. Such familiarity has so far been difficult to obtain. Hujar published one book during his life time, the 1976 Portraits in Life and Death. The book had been out of print until this month. Now, there is a much overdue reissue.

Hujar has so far been shoehorned into being a very specific photographer: a photographer not just of any time and place, but one who lived in New York City before and during the AIDS crisis. His own untimely death at age 53 would include him in the countless victims of that disease — at the time, they were stigmatized in the most revolting fashion.

Of course, Peter Hujar was very much a member of New York’s artistic community, and the death toll created by AIDS is very much real. When I wrote that he was being shoehorned, I do not intend to take anything away — on the contrary. What I mean to argue instead is that beyond that specificity in time and place, there is a universality in his work that deserves to be seen more widely.

It’s a trite statement to say that portrait photography uniquely centers on the human condition. The moment you place yourself with a camera in front of someone who has agreed to be photographed, the resulting picture (or pictures) will say something about the human condition.

What makes photographic portraiture so interesting is that if you take a picture of someone famous, most people will obtain a picture of someone famous. In his very good pictures, though, Hujar was able to create photographs of human beings, people as brilliant and flawed and vulnerable and lonely as he was, and the fact that they were famous plays no role in any of that. You can see people with an inner life, possibly a very rich one.

Being able to take these kinds of photographs is a gift that even someone like Hujar was not able to conjure at will. In Peter Hujar’s Day, a conversation with Linda Rosenkrantz about a single day in the artist’s life, Hujar somewhat casually re-narrates how on 18 December 1974, he set out to photograph Allan Ginsberg as a commission piece for the New York Times.

Long story short, he treks over to what at the time was one of the seediest areas in Manhattan, 10th Street between Avenues C and D. “The neighborhood intimidates me,” he tells Rosenkrantz, “it’s frightening, so run down and dreary. I don’t have any real fear but it’s very uncomfortable to go down there.” Thinking that Hujar somehow is much more connected to the Times than he was, Ginsberg at first acts like a real jerk, only to warm up a little later (in the way that an incredibly chilly morning might do in mid-winter).

The photography session unfolds as a real disaster. Ginsberg breaks out into chanting at various times (“He sat down in the lotus position, looking very Buddha, right in the doorway, and started to chant. And I really thought well, I can’t interrupt God.” — Hujar), but there are pictures for the photographer. And he knows that these pictures are of the first kind I mentioned above: they’re of someone famous. But they’re not more than that.

After all, even for someone as gifted as Peter Hujar, there is only so much that can be done when the stars do not align in the right fashion as someone’s portrait is being taken. You can see one of the Ginsberg photographs here.

What it is (or rather was) that enabled Hujar to align the stars in just the right fashion I don’t know. Of course, there are all the statements made about Hujar by those who knew him (many of them found themselves in front of his camera; many of them the kinds of irritating motormouths New York tends to produce in such abundance).

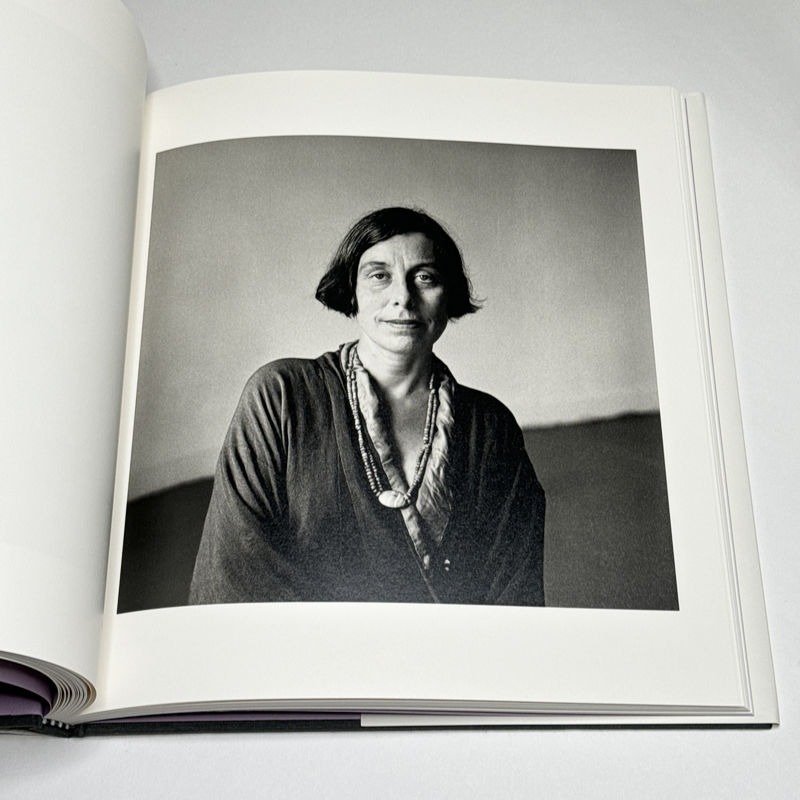

Susan Sontag, a close friend, wrote the introduction to Portraits in Life and Death, which is included in the reissue. The portrait of her by can be found in the book. I suppose it’s maybe the one photograph by this artist that is more widely known. Alas, it’s also just a picture of someone famous. It’s very good. But it doesn’t go where many of Hujar’s real treasures went.

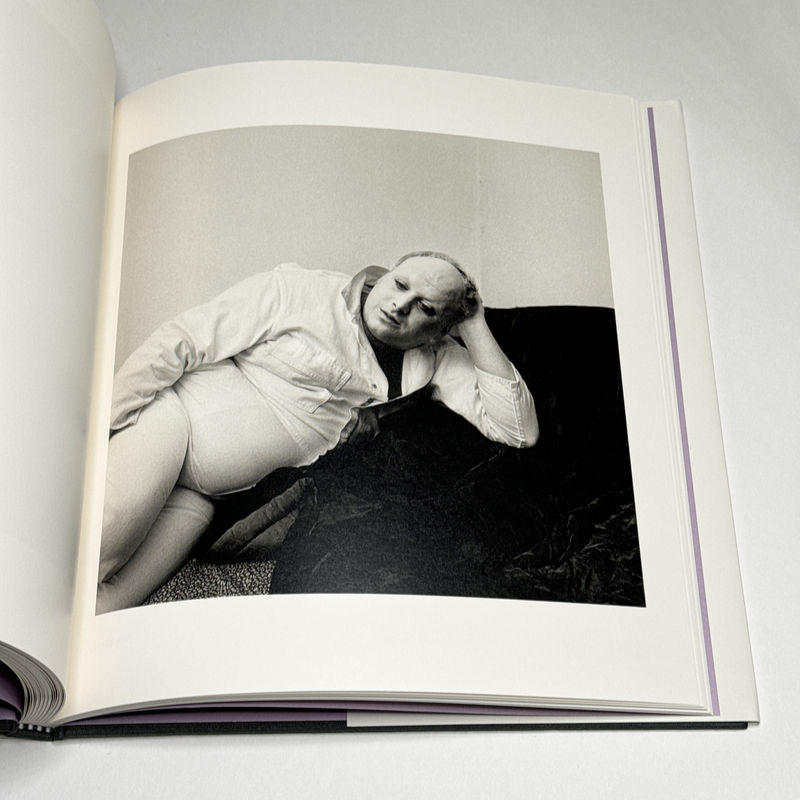

I’m thinking that Peter Hujar knew of the power a camera can have because he placed himself in front of his own many times. There are two such picture in the book. The first shows him mid leap in his own apartment, giving a military style salute to the camera. This is brilliant. It’s not necessarily a masterpiece photograph; but I don’t think I can imagine another photographer, living or dead, who would pull this off (other than, maybe, Nadar whose photographic materials were way too slow to allow him to do this).

The second photograph can also be found on the cover of Peter Hujar’s Day. It shows Hujar lying in bed. His arms are raised above his head and rest on the pillow. The photographer has turned his head just enough for him to be facing the camera.

I have no way of knowing whether this photograph was made on the same day that he took my favourite photograph of his (which, alas, is not included in the book). In that photograph, Hujar, fully nude, is slouched on a chair. To say that there is a quiet desperation on view would be to take words to describe a situation that exists outside of language itself. The photograph is entitled Seated Self-Portrait Depressed, 1980.

It’s one thing to expose others to the camera’s cruel gaze. It’s quite another to be as relentless in exposing yourself to it as Peter Hujar did. He knew what it meant to suffer. So he knew what he was asking of others when they presented themselves to his camera. That, and only that, is what it takes to be a really great photographer.

When you look at Portraits in Life and Death, you want to ignore everything you know about those portrayed (there’s an index in the back). Instead, try to see the human beings that Peter Hujar saw.

Highly recommended.

Portraits in Life and Death; photographs by Peter Hujar; essays by Susan Sontag and Benjamin Moser; 100 pages; Liveright; 2024

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing to my Patreon. There, you will find exclusive articles, videos, and audio guides about the world of the photobook and more. For those curious, there now is the possibility of a trial membership for seven days.

Much like journalism, photography criticism involves a huge investment of time and resources. When you become a subscriber, you not only get access to more of my work. You will also help me produce it (including the free content on this site).

Thank you for your support!