I have long thought of photography as being centred on what you do with cameras and photographs — instead of merely as being centred on cameras and photographs. In other words, I see photographs as means to an end — and not as the end itself. Of course, I enjoy a lot of photography that ends with printed pictures in expensive frames. But ultimately the fetish of the print bores me (it helps that all the photos I like are priced way out of my reach).

There’s something very restrictive to having photography centre on the fetish of the print, or maybe the printed picture. Over the past few years, I’ve seen a lot of photography that looked great as part of the stream of images on Instagram but fell completely flat when printed. This is as much an issue of translation (screen to print) as of context. Some pictures rely on the context of the stream: instead of losing their lustre (as critics like to claim), they actually gain from sparkling as the gems they are when surrounded by mediocrity.

If you instead think about photography as what you do with cameras and pictures, it’s almost inevitable that you’ll end up in social contexts, the same social contexts that under neoliberal capitalism have become increasingly impoverished, to the point where we now mistaken typing short messages into our smartphones in isolation as being “social.”

In a social context, there is a give and take — this sits at the core of something being social. The opposite of this would be to only take. Photographers take pictures. Thus, on its own, and if it ends there, photography is an extractive practice.

Over the past few months, I’ve seen this word used more and more: extractive. To extract is to take something and make it your own. Extraction is inherently tied to capitalism, especially its neoliberal kind that does away with any social obligations.

But photography can be more than extraction, because there is what you do with pictures. Like I noted, you can print your pictures and hang them on a wall, adorned by expensive frames. That way, you mostly aim for beauty (let’s ignore the inevitable commerce bit). The idea of beauty is social, too: if I find something beautiful and I can’t find a single other person on this planet who does as well, is that still beauty?

The appreciation of visual beauty, however, is not social (especially when compared to music). At San Francisco’s Pier 24, they only allow in a small number of visitors so each person can enjoy the photographs on their own. I personally find this not enjoyable at all (it’s actually rather creepy).

I would rather go to a museum and not only look at pictures but also notice other people looking and reacting to what is on view. I personally prefer the shared experience, even as what is shared is literally only the fact that something unsharable — an interior experience — is happening in the presence of strangers.

I suppose what this comes down to is that I enjoy photography that is made to be shared. This is part of the enjoyment I get out of good photobooks: beyond the pictures, there’s something else happening, someone thinking about how to shape a unique experience. With its many different options, the photobook also allows for photography to move beyond its extractive state.

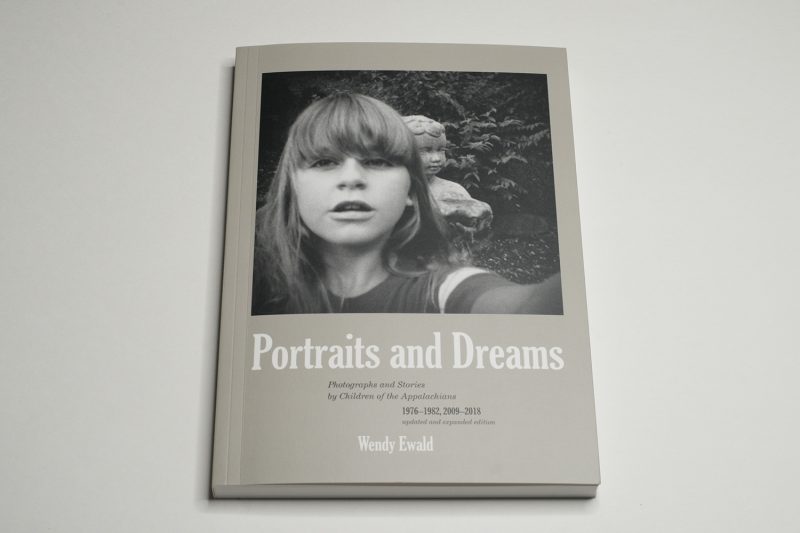

A prime example of how photography can overcome its extractiveness is provided by Wendy Ewald‘s Portraits and Dreams: Photographs and Stories by Children of the Appalachians, recently reissued by MACK in an updated and expanded version (full disclosure: MACK are going to publish an expanded version of one of my essays as part of their Discourse series.).

In 1976, fresh out of college, Ewald moved to a very rural part of Kentucky and started teaching photography to children there. Like many parts of the United States, Appalachia has a stereotype affixed to it. If we just stay with photography this has resulted in its people being portrayed in ways that might be unique for the US: typically, it only is regions — or whole countries — elsewhere, far away, that were or are being depicted in such a skewed and cruel manner. To learn more, this interview with Roger May is a good starting point.

“The students,” Ewald writes, “bought ten-dollar Instamatic cameras from me; I hoped that by buying the cameras they would value them as things that had worked for and would have as long as they took care of them. If they didn’t have the money, they earned it by mowing lawns, or holding a bake sale or a raffle. I supplied the students with film and flash.” (p. 113)

The majority of photographs in the book were taken by the children — as is evidenced by their technical qualities. In one of the texts in the book, there is talk of a Hasselblad camera Ewald used. There are some photographs that clearly look as if they had been taken with such a camera. Mostly, though, the pictures have an Instamatic look.

In addition, the majority of the photographs come with a name and caption underneath. For the most part, these captions are prosaic descriptions, even though at times, the children also talk about the ideas that went into the photographs they made (“I dreamt I killed my best friend, Ricky Dixon” — Allen Shepherd, p. 96).

There also are extended texts that read like transcriptions of what the children told Ewald. Again, these texts range from the prosaic to the profound — in a way that only children could come up with. In a nutshell, it is the children who tell the story of their part of the world through their photographs and words.

The children’s photographs were the outcome of assignments: make a portrait, make a picture of a dream. How does one go about making a picture of a dream? Adult artists would probably agonise over such an assignment. But children just do it: there’s the dream, so you assemble your props and, where needed, a friend, and then you make a picture.

“In 2008,” Ewald writes, “[…] forty years after I began collaborating with the students whose photographs appear in the book, many of them, now in their forties, started to get in touch.” This is the first sentence in her brief essay that marks the beginning of the expansion of the original book. Here, some of the students speak about their lives now, again with a mixture of text and photographs.

Portraits and Dreams offers such a strong counter model to photography’s extractiveness that it deserves to be seen for that alone. At the same time, though, the book also provides an endearing look into the lives of people who grew up in Appalachia, often with rough family lives.

At the end of the day, every photographer will have to make her or his own decision concerning how to deal with what the medium has to offer. As I have argued before, s/he will also have to deal with the fact that the age of innocence in photography is truly over (assuming it actually ever existed). There just is so much baggage from the history of the medium that many areas of photography are incredibly problematic.

This does not necessarily have to translate into a prohibition of entering those areas: maybe there are other ways of dealing with a subject matter that avoid obvious problems? As Wendy Ewald demonstrated when Portraits and Dreams was first published, you can make work in Appalachia that does not reduce the area to the bad stereotypes that, sadly, are still being produced today.

It is exactly here where thinking about photography as a social practice — and not as some fancy craft — can help. For the fancy craftsmen any discussion of (for them) unforeseen consequences of their work always amounts to something unpleasant. More often than not this outcome would have been completely avoidable if the process of photography had not been stopped with the pictures.

If anything, Portraits and Dreams demonstrates what is gained from allowing your subjects to enter your work as active participants — instead of being merely subjects whose picture you take. Or, in Wendy Ewald’s words: “these students taught me the guiding principle of my life’s work: to frame the world according to others’ vision, as well as to my own.” (p. 125)

Recommended.

Portraits and Dreams; photographs and texts by Wendy Ewald and her students; original introductory essay by Ben Lifson; 160 pages; MACK; 2020

I’ve set up a tip jar. If you’ve enjoyed this article (or site), feel free to leave a tip to support my work. Thank you!

Also, there is a Mailing List. You can sign up here. If you follow the link, you can also see the growing archive. Emails arrive roughly every two weeks or so.