It’s a bit of an understatement to say that there’s a lot going on in the world of US politics right now. I believe that a much larger majority than the one that already exists will come to regret this time bitterly. But I’ll leave it to others to comment on the various injustices committed in the name of the American people. If there’s one thing I had not quite anticipated is what role and importance photographs would have and play, though.

Specifically, while I have always spent a lot of time looking at how a photograph’s form and content might inform each other, I had not expected such discussions to spill out into the larger area of the news, which to some extent they now have done. Outside of the narrow confines of photoland, photographs mostly tend to be discussed based on what they show and not how they do it.

Under the Obama presidency, for example, this fact helped create an image of the man that, for me at least, is at odds with what that man actually achieved in office. But Obama knew how to look and act cool, especially in photographs — something that was part of his appeal. His supporters very clearly enjoyed the idea of having a cool president, someone who would drop the mike and do all the stuff the cool kids do.

You can’t say the same thing about Donald Trump. It’s not up to me to attempt to analyze these two men’s personalities from the distance. I’m neither qualified to do so nor interested. Based on the photographs that have emerged, it’s obvious that they both are incredibly image conscious.

This observation might not surprise anyone who is familiar with the incredibly shallow world of presidential campaigns where a single “bad” photograph can ruin your whole candidacy, however qualified you actually might be for the job. You just have to be good with pictures to become president — those who will vote for you must like what they see. It’s very visual. You must attempt to project exactly those qualities your voters want (and make sure the photographers deliver them — here, you’re usually in collusion with the press, which will be happy to go along).

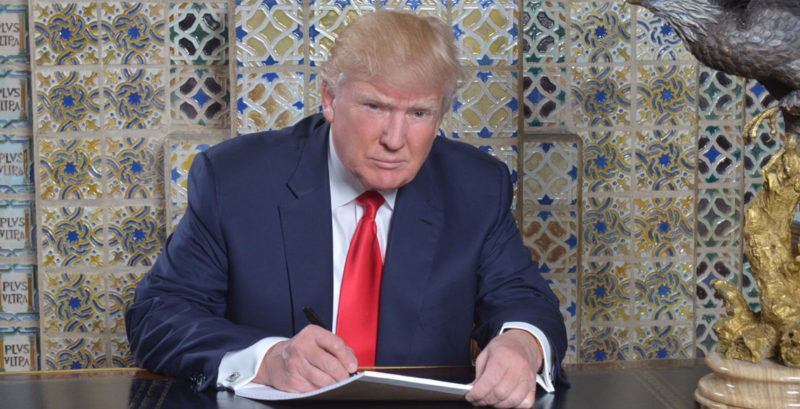

This is the background against which I look at photographs from the political arena. The other day, I burst out laughing when I saw the photograph on top here, which Donald Trump tweeted on 18 January, 2017: “Writing my inaugural address at the Winter White House, Mar-a-Lago, three weeks ago.” It’s a pretty amazing picture, isn’t it? To begin with, he is so obviously not writing anything — you would have to be a complete and utter fool to believe this. Yet somehow, he seems completely unaware of the fact that the picture gives this away in such an obvious way. That’s comedy, right there, Alan Partridge style.

Once my laughter subsided, I couldn’t stop looking at the picture, though. To begin with, everything about this picture gives me the impression I’m dealing with an image straight out of the Soviet Union — or maybe one of those landlocked post-Soviet Asian republics that are ruled by some pompous autocrat. To begin with, the colours are just so weird. It looks like what you’d find in an older book that was printed using some pre-CMYK process, where all the colours would be a little strange, and only red (the Soviet colour) would stand out so much. Of course, the decor plays into that, those weird tiles (where do you even find those?), plus what might be a completely tacky desk statue of an eagle. I’m still incredibly fascinated by the picture for all these different reasons, including, of course, that it was made and disseminated in 2017.

“He’s very difficult to photograph,” Martin Schoeller said after having been tasked to do exactly that. “He literally has one angle. If I ask him to smile, he puts on a big grin and then he goes back to his Zoolander ‘blue steel’ look.” So clearly, the “speech-writing” picture features that Zoolander look. And you’ve probably seen this look quite a bit, given it’s what Trump prefers for his official photographs. It’s quite different than the cerebral, yet somehow cool Obama look, isn’t it? But ignoring the differences between these two men, the overall idea is exactly the same, namely to project an image.

How much Trump is obsessed with image became even more clear when the “controversy” erupted over the turnout at his inauguration. I put quotes around the word “controversy,” simply because I’m not even going to entertain the idea that “alternative facts” should somehow be taken seriously. Obviously, a lot less people showed up for Trump than for Obama eight years earlier, and obviously that was clearly visible in the photographs.

There’s something in Trump’s personality that has him pick fights that make him look even worse when he already looks bad. So he not only kept talking about it himself, he also sent his minions out to make complete fools of themselves (which they happily did). I found that all completely fascinating, because at the basis of this all were discussions about photographs. The photographs very clearly showed what had happened. Yet here were people who had been just handed a lot of power arguing that somehow this all was wrong. Only explanation: There had to be other photographs that showed a larger crowd. There weren’t.

Why does this matter? Or how? There are a lot of discussions now about photography and the news especially, and how about people don’t trust the news any longer. The irony here is that the people who create fake news and spread it around do so claiming you just can’t trust the news. Anyway, given it is so strongly connected to the news, this lack of trust supposedly has repercussions about photography, in particular with respect to the topic of “manipulation”.

I think all in all this problem is very similar to the issue of voter fraud: it does exist, but it’s a very small number. Voter fraud is not a problem because it exists. Especially right now, it’s a “problem,” because there’s simply no other way to account for the fact that Trump got almost 3 million less votes than Hillary Clinton. In other words, it’s a conspiracy theory.

In much the same fashion, image manipulation is not a major problem for (news) photography. People don’t mistrust photographs because they’re manipulated, they mistrust photographs because they don’t show them what they want to see. Donald Trump just provided a clear example (follow the link about the crowd size). This doesn’t necessarily mean that we, in the world of photoland, should relax our concerns about manipulation and what can or should be done etc. But we ought to realize that a large part of the problems that are attached to photography come from the outside and have nothing to do with the medium.

I’m getting to the point where I’m becoming a bit exasperated that discussions around manipulation never seem to talk about this simple fact. If people don’t want to believe your pictures because there’s a conflict with what they believe in or want to see, that’s not your problem. That’s not an issue of how much you can tweak this or that adjustment layer in Photoshop (or Lightroom or whatever else you might do). This is a much more fundamental problem, and you simply cannot solve it by buying into it (if you don’t believe me, try arguing with a conspiracy theorist about UFOs — you just can’t win, because every fact that refutes their idiotic ideas simply points at an even larger conspiracy).

Consequently, I believe photographers ought to play to their strengths. We need to have open and honest and in-depth discussions about photography, without buying into the crazy. Where unacceptable manipulation happens, we need to point it out. But the world of photography will only gain trust by producing high-quality work that has been done with integrity and respect. That’s all it takes. Not more, but certainly not less.

On top of that, given that discussions around photographs are now being started, we should make sure they get expanded. The conspiracy theorist in the White House wants to talk about what the pictures show? OK, let’s do it! That’s great! Let’s give the larger public more insight into what pictures show, how they do it, and how the “what” and “how” are related.

Larger problems such as vast parts of the population angling for “alternative facts” aren’t a problem for photography. This complex is a larger societal problem that, of course, we all need to work on as well — not as photographers, editors, critics, but as engaged citizens. So we need to step outside of our photoland bubble just as much as reach out of it: of all the people qualified to speak about photographs, it’s the members of photoland that are most educated and capable of doing exactly that.