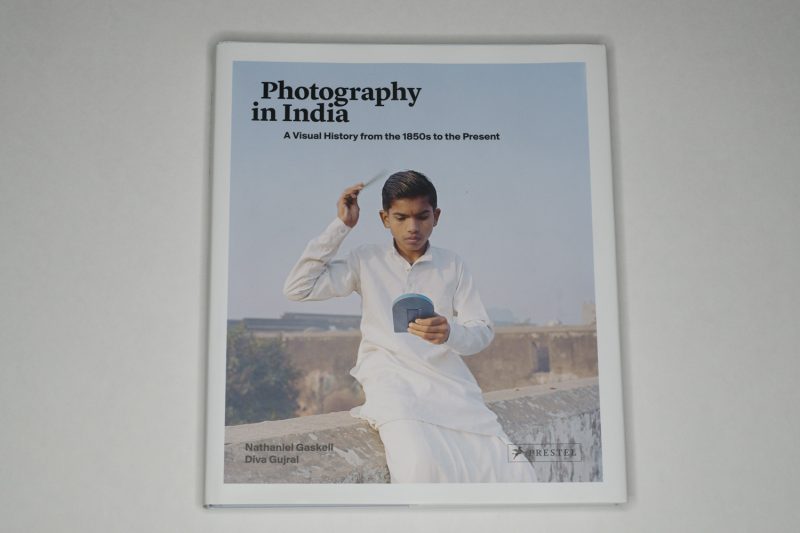

“The erroneous understanding of anthropology coupled with the deeply problematic way in which the subject is rendered, as well as the speed at which it was digested by Western audiences, sets the tone for much of the way early photographs made in India functioned.” This sentence, taken from the description of the very first photograph that is discussed in detail in Nathaniel Gaskell and Diva Gujral‘s Photography in India, sets the stage not only for what the reader is going to encounter time and again in the book, it also explicitly spells out how photography from its earliest days was a medium filled with huge problems, most of which have not gone away 180 years later.

Photography’s dark side is curiously underexplored. Its being a willing handmaiden in humanity’s worst excesses, some of which cost millions of people their lives, is known to academics and some critics and artists. However, for the most part this aspect of photography’s history continues to be glossed over with silence, resulting in discussions of, for example, the Other often being led from perspectives of curious ignorance.

Seen this way, Gaskell and Gujral’s decision to write Photography in India and not Indian Photography makes sense in more ways than one. To begin with, photography in India cannot be understood without the work produced there by people not native to the country — first the colonizers, later visiting artists some of which have been delivering neocolonial fantasies (more of this later). Indian photographers, in other words, cannot escape working in an environment whose visual understanding in the West to a large extent has been shaped by foreigners.

At the same time, while the book focuses on photography made in and about India, its themes apply in some variation also to many other countries, in particular if they were at some stage also colonized by Western powers. I’m not sure this is a situation that can be understood easily by most Westerners, a situation where your own history and culture have already been told in a very simplified, distorted, and demeaning manner by people who clearly didn’t (and often still don’t) know and/or care to do better (imagine signing up on some social network, and there’s already your profile with all kinds of demeaning and nasty stuff set up by other people, none of which you can change).

The photograph from whose description the sentence above was taken is not the first image in the book, but it’s the first one discussed in detail. It’s such a ghastly picture, though, that it might take the viewer a while to be able to read the text. Entitled Andamanese group with their keeper Mr Homfray (1865) and produced in the studio of John Edward Saché and W.F. Westfield (in then Calcutta), it shows Mr Homfray (fully dressed) and seven Andamanese people (naked), with the latter curiously arranged around the former. When I first saw it, it took my breath away (but not in a good way). It’s a very violent picture, and the violence is structural. It’s an image of oppression.

A different type of oppression, albeit one most Westerners will be more oblivious of, is given space a few chapters into the book as “The New Exotic.” Here, some of photography’s (supposed) greats are revealed as perpetuating what I usually think of as a neocolonial fantasy. In the authors’ words: “the photographs fix India in a designated past, a ‘there and then’, out of which its inhabitants cannot escape.” The photographer — whether Henri Cartier-Bresson, Marc Riboud, Don McCullin, or Steve McCurry — here becomes “a sort of time traveller who, in photographing India, appears to reach into the past in order to bring an ‘authentic’ India to light.”

Obviously, Photography in India not only focuses on the visual abuse the country has suffered at the hands of colonial or neocolonial photographers. There is ample work included by non-Indian artists that has much to offer, and of course there are many Indian photographers featured whose names might not be very well known (yet). Dayanita Singh and Raghubir Singh both recently became known in the West. One can only hope that many of the other artists featured in the book will be lifted out of their obscurity in the West.

The reader/viewer will inevitably gravitate towards what s/he most strongly responds to. I found myself mesmerized by Annu Palakunnathu Matthew‘s An Indian from India, Ketaki Sheth, Sohrab Hura. Of course, there also are the photographs from Suresh Punjabi’s Studio Suhag, even though there I’m torn between my own delight coming across the photographs and my concern over their own becoming a bit too much of a spectacle for the possibly wrong reasons (as always, your mileage might vary).

All of this makes Photography in India a book that anyone seriously interested in photography might not want to walk past. It crucially pulls back the curtain that still conceals too much of the medium’s horrible past and its ongoing contemporary abuses, while opening a large variety of views of a complex country (that has more inhabitants than the US and Europe combined).

I’m hoping that the approach used for and in the book will be emulated should other authors decide to approach other countries whose reception and photographic treatment in the West has been equally problematic.

Highly recommended.