Photography is not interesting because of what it shows; it is interesting because of what it does. By that I mean its uncanny ability to trigger ideas, thoughts, and memories in ways that are largely outside of our own control.

That’s why debates around what critics have called compassion fatigue are such a dead end. Those debates only focus on what photographs show (as terrible as that might be). Crucially, they assume that human beings are simplistic creatures that can be swayed by a photographer’s (or editor’s) intentions — as if those were magically present in the photographs. And when that doesn’t work, it’s somehow the viewers’ fault.

In reality, our minds are more complicated than that, and for all kinds of reasons (some good, some bad) we might not be swayed the way someone intended us to be.

In essence, photographs might move us for reasons nobody could have foreseen — not a photographer or editor, and certainly not we ourselves. If it were otherwise, photography would only be a blunt propaganda tool (which, of course, it sometimes is — just not most of the time).

It was telling that years ago, when I occasionally asked students working towards an MFA whether they were looking for beauty, every single one of them recoiled in horror (a horror usually barely hidden behind a mask of politeness). Beauty was suspicious, something not to be touched.

After a while, I figured out that it was probably because you can’t control beauty or will it into being. But beauty also was something those outside of the narrow confines of the art school might appreciate (the frequent rejection of an appreciation of beauty in the world of art is little more than barely disguised elitism).

Of course, beauty is everywhere in photography (usually just not where MFA students want it to be), and it plays a crucial role in undermining our critical facilities to make us face truths about ourselves that we’d rather not deal with.

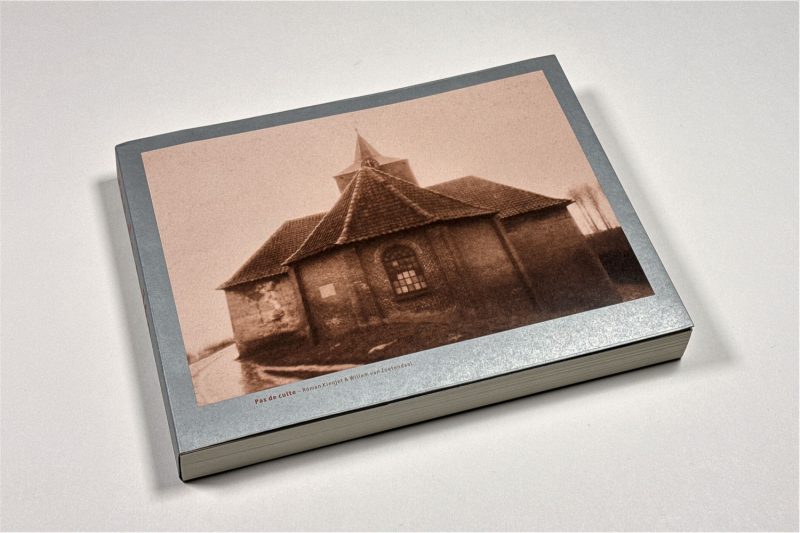

I had to think of all of the above when trying to find out why Pas de culte, a new book created by Róman Kienjet and Willem van Zoetendaal moved me so deeply. A collection of photographs of places of worship (the majority of them Christian churches), sourced from various Dutch collections and archives — I would not have imagined I might even be interested in this.

In the end, it probably comes down to a set of factors. Many of the photographs reminded me of the kinds of structures I would see near where I was born, the locale I grew up in. What is now the northwest of Germany visually is very similar to larger parts of the Netherlands (it is, in fact, part of a larger structure called Frisia).

In this relatively featureless flat land that for centuries has been beaten down by strong winds and occasional storms (that up until not so long ago brought regular flooding), many of the churches in the many little hamlets and towns in the countryside are bulky and sturdy. In essence, they’re hunkering down in advance.

If you drive across the land, you’ll spot the next hamlet first by seeing the top of its church. Anyone familiar with landscape paintings from the Dutch Golden Age will be familiar with this: within the somewhat nondescript land and the vast expense of sky, you’ll occasionally spot a church which will guide your eye towards the city it is a part of.

Pas de culte shows you some pictures of what this kind of landscape has been looking like ever since photographers arrived on the scene. In addition, there are many other pictures of churches (and other houses of worship) that bring you closer to details, whether it’s their facades or their typically bare bones interiors.

As I noted, I was born into this protestant landscape. I realized many years ago (as a teenager in fact) that I never believed in the Christian god and the various stories around them. At first, this realization felt like a small crisis (in particular since it happened during the “classes” I had to take for what was called confirmation).

With a little time, I was able to shake the mental shackles of the Christian thought that had been embedded in my mind. The faith that I was born into but that I did not have became just another one of the things tied to a past long gone.

But here was this familiarity, triggered by the visuals of the stout churches in small Dutch hamlets that can be found in Pas de culte. I was reminded of the wind, of the sparseness of the land; I was reminded of how the land’s unforgiving nature had carved deep lines into the minds of the people living there, how it took me many years to shed those lines to instead embrace my current more forgiving self.

And then there’s the beauty, or maybe rather the aspiration towards it — not so much the beauty of the buildings (your mileage might vary) but beauty as an ideal to strive for: the beauty of a life lived in community with other human beings that are seen and treated as equals.

Even as Christianity has fallen woefully short of its own central message (and continues to do so every single day), the aspiration itself is beautiful, and it also hints at the beauty our world could take on if we all adopted the idea (the idea, not the religion).

Seen that way, beauty becomes subversive (and maybe that’s also why those MFA students were so eager to run away from it): beauty reminds us of how flawed we are as human beings, and of how little we often do to attend to those flaws in an attempt to at least reduce their numbers.

I don’t have to describe how in this particular moment, as the worst human instincts have taken over our body politic, wrecking havoc with people’s lives and well being, the idea of beauty has its most political moment: to insist on beauty is to resist.

And resist we must.

Highly recommended.

Pas de culte; photographs by Pieter Oosterhuis, G.H. Breitner, Alfred Stieglitz, Adolph Mulder, Ed van der Elsken, and numerous others; edited by Róman Kienjet and Willem van Zoetendaal; introduction by Róman Kienjet; interviews with Marinus Boezem, Paul Kooiker, Marc Mulders, Fiona Tan; 288 pages; Van Zoetendaal; 2025

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing to my Patreon. There, you will find exclusive articles, videos, and audio guides about the world of the photobook and more. For those curious, there now is the possibility of a trial membership for seven days.

Much like journalism, photography criticism involves a huge investment of time and resources. When you become a subscriber, you not only get access to more of my work. You will also help me produce it (including the free content on this site).

Thank you for your support!