As Western societies get richer and richer under neoliberal capitalism, the accumulated wealth is distributed more and more unequally. The problem isn’t just that a relatively small number of people (billionaires) are hoarding money like modern-day Crassi. The real problem is that what not so long ago was referred to as the 99% is no homogeneous block.

Just look at how what used to be social-democratic parties are now organizations devoted to preservation and betterment of the relatively well off. Beneath those, there is a growing assembly of citizens that politically and economically are not represented by anyone any longer and that have been stripped of whatever few rights and little wealth they might have been able to accrue under previous social-democratic conditions.

As a consequence, those at the very bottom of the economic ladder have become outcasts, regardless of whether they are refugees from foreign countries, stateless wanderers, or the kinds of economic losers whose presence is necessitated by the collusion of billionaires and the clients of “reformed” (“centrist”, “third way”, …), previously social-democratic parties. Those that advocate for the vast new underclass are now usually described as “far left” by the media that are solidly devoted to “centrist” ideas, and they often lumped together with the far right, as if social justice and fascism posed equal threats to democracy.

As can be seen in a large number of countries, this situation is toxic for democracy itself. If people are given the choice between neoliberal technocrats whose main focus is “the economy” (resulting in ever shrinking social services while taxes on corporations and the rich are lowered) and neo-fascists who offer a vision, as noxious and outright dangerous it might be, then in the long run the neo-fascists can only win, leading to the likes of Trump, Orban, Kaczynski, Le Pen, Bolsonaro, Modi, etc.

It’s easy to see how this configuration poses a lose-lose situation for democracy. A neofascist victory typically results in the erosion of democratic norms and rules (if not their outright suspension as courts are being politicized etc.). To prevent that situation, many people feel blackmailed into voting for the “lesser evil”. But that erodes trust in the democratic process itself, given people are led to think that there is no choice whatsoever. This in turn feeds the neofascist narrative that liberal democracy is the problem.

How would one go about photographing around any of this? French photographer Myr Muratet‘s Paris Nord focuses on a number of aspect mentioned above. If I understand the publisher’s description of the book properly, the book combines a number of projects and intermingles them to arrive at a searing indictment of the very mechanisms that are driving more and more people into the margins.

(It is a coincidence that I am writing this article on the day of the first round of the French presidential elections that once again resulted in the choice between a neoliberal technocrat and a neofascist that openly supports Russian dictator Putin.)

There are a number of reasons why the book is extremely noteworthy. To begin with, it’s filled with a number of incredible, visceral photographs. Even as many of its ideas aren’t very new at all, every time I look through the book I can’t help but feel that this is a milestone of photography that shows me something I am familiar with in a new light, rattling the cage that most of us find ourselves in.

It’s strange: Photography originated in France. And yet over the past few decades, the country hardly has been at the forefront of contemporary photography, even as some of photoland’s most cherished events are happening there (Paris Photo and Les Rencontres d’Arles). These days it’s mostly artists from its central and eastern parts that are pushing the conversation forward in Europe. In some ways, France reminds me a little bit of Britain before the arrival of a new generation of photographers working in colour in the 1980s re-ignited the fire there. Will we be able to witness a similar revival in French photography now? Paris Nord for sure is a book that I hope will make its mark and stake such a new claim.

As an object — and this is something I have to get out of my system, the book isn’t particularly attractive. It’s a relatively large softcover with a clear plastic dust jacket and a paper that’s rather unattractive to the touch. It’s testament to the sheer strength of the photography that this hardly matters. Possibly, the book was made with costs in mind: on the publisher’s website, the book is listed for 25 €. That’s crazy cheap for what you get when you buy a copy. And potentially making more of a luxury object would run counter to what’s presented in the book.

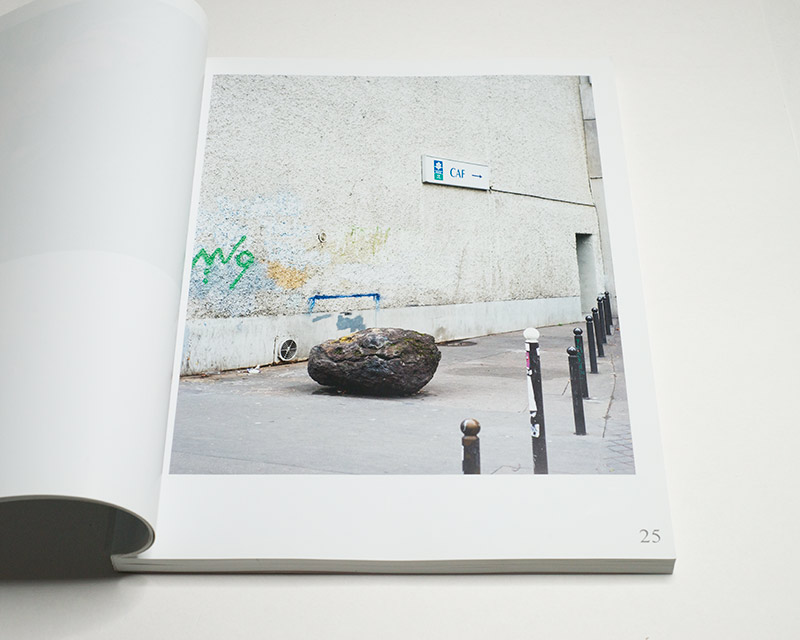

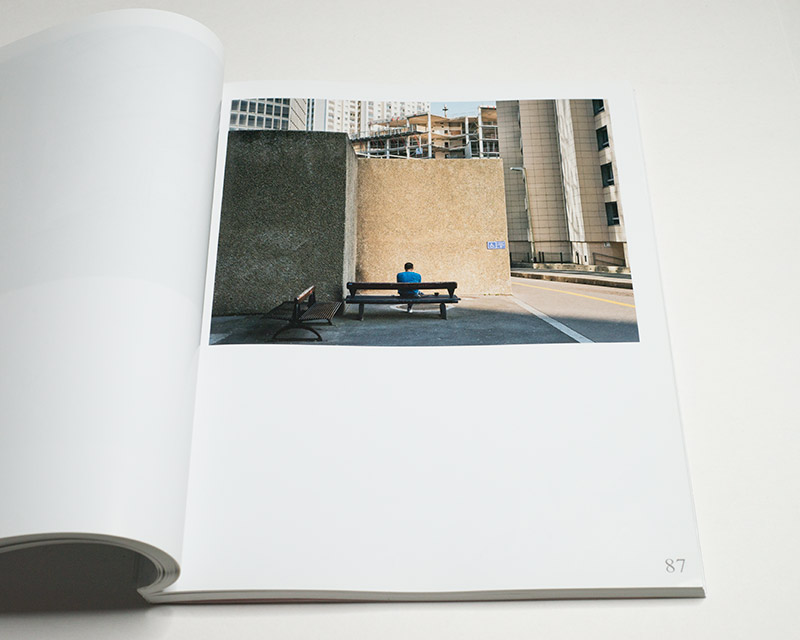

Regardless, as you leaf through the book, you encounter an urban environment that is openly hostile towards at least some of the people who are trying to find a home there. Muratet is very adept at photographing Paris in such a way that the various contraptions created around its inner-city buildings designed to keep out people without homes resemble the fences and barriers around motorways or other areas that are not to be entered. The City of Love has thus become a mirror of neoliberal violence: if there’s love, it’s strictly kept from anyone who finds themselves at the margins.

There are many photographs of these people. After all, they have no choice but to try to make the city their home, regardless of whether they’re welcomed or not. Some of the most searing pictures show people sleeping in what essentially are body bags for bodies that are still warm: large sheets of plastic or maybe thin fabric that delineate the sleepers’ contours. These photographs show how much these people are worth to the French Republic in which they find themselves in.

If you find my read of these photographs too drastic, consider the case of René Robert, a Swiss photographer aged 85, who one night slipped somewhere in Paris and then spent a total of nine hours lying in the street helplessly before he died from hypothermia. Not a single Parisian bothered to check whether the main lying on the ground was OK or not. We only know of Robert’s fate because he had friends in well-off circles. If one of the people depicted in Paris Nord dies, we will never hear about it.

If it is sheer indifference that resulted in the death of René Robert, Myr Muratet’s should be seen as an act of resistance: Indifference is a choice, whether in the voting booth, on the street, or when walking around with one’s camera.

Paris Nord is an exceptionally strong photobook that you don’t want to miss.

Highly recommended.

Paris Nord; photographs by My Muratet; essay by Manuel Joseph (French only); 240 pages; Building Books; 2021