Something curious happened a few days before I received Sophie Calle’s Overshare, the catalogue of a recent retrospective of the French artist’s work. Describing Voir La Mer to a group of photographers, I told them that Calle had brought people who had never seen the ocean to it so that they may see it for the first time. But, I said, she had only filmed (or photographed) them from the back. A viewer would have to imagine this particular moment in these strangers’ lives. Alas, Overshare showed me, I had misremembered Calle’s art piece; or maybe I had tweaked it mentally towards what I would have shown. Instead, after Calle’s subjects had faced — and seen — the ocean, at the artist’s request they had turned towards the camera so that we, the artwork’s viewers, would see their faces (meaning their eyes).

Thinking about this seemingly inconsequential episode, it seems to me that what I had misremembered was not so much one of Sophie Calle’s minor pieces (your mileage might vary). Instead, I had put my own interpretation of this artist onto it. Calle’s work has been very, very dear to me for many years, and I have spent a lot of time with it.

In her introductory essay, curator Henriette Huldisch writes how Calle has had to fight with what male artists never had to contend with. While, for example, writer Karl Ove Knausgård’s generous (and if you ask me completely insufferable and self-indulgent) oversharing has never counted as anything other than major literature (even as that writer’s seemingly endless revelations of life details end up being an exercise in vapid form: so many books, so many pages), for women artists such as Calle that process has not been quite as easy at all, with frequent criticism leveled at what to many people (for all the wrong reasons) did or does not look like art.

I could see how my misremembering might be seen as yet another older guy seeing a woman artist’s work in the wrong light. And yet, I will contend that my misremembering was instead fueled by my familiarity with Sophie Calle’s best pieces. While oversharing can be seen as being an essential aspect of the French artist’s work, to see it as just that or, maybe more precisely, to end the discussion right there runs the risk of missing the key characteristic of her work. After all, there is a reason why Sophie Calle is considered to be one of contemporary art’s most poignant practitioners while the stars of today’s (and by now yesterday’s) reality-TV shows are not: very crucially, Calle’s sharing stops where the real hurt begins. In contrast, in reality-TV shows, the hurt is spread out for all to witness, typically with gratuitously overscripted neoliberal solutions added at the end. Reality TV might be TV, but it has nothing to do with the reality we experience in our lives.

The point of most of Calle’s works is not so much what is being shown — as revealing as it might be. For example, inviting strangers to sleep in your bed while photographing them is transgressive in some ways (even though in the age of AirBnB and the discovery of hidden cameras, that transgressiveness has faded considerably). However, the point of The Sleepers is that the feelings that might arise — and this is where Calle’s work and reality TV depart radically — are being left to imagine. In other words, what makes most of Sophie Calle’s work so radically emotionally potent is not a revelation, however far it might go, but instead the frustration of a viewer’s desire for the painful or deeply emotional moments to be resolved. And that’s exactly why I was so disappointed to see the faces of the people who had seen the ocean for the first time.

Sophie Calle’s art thus is life, our daily life, a life that unlike reality TV is not lived around the same repeating script. For all of us, The show will be over at some point. But we won’t know whether there will be the beautiful resolution just in time or a cliffhanger (that, granted, we will not be around to deal with any longer). Chances are that some things will simply not be resolved. Put bluntly, Monique, Sophie Calle’s mother who was reported to have proclaimed “Finally!” when she became her daughter’s subject on her deathbed, is not around any longer to see the piece.

There is a distinct and at time very strong red thread of transgressiveness in Calle’s work. It’s not in all pieces, but it shines through over the years. Sophie Calle always wants to know more about someone than what might be “proper”. This is interesting, because what actually is proper often is not clearly defined. To give a completely unrelated example, when I went to Japan, a few strangers told me things I would have never dared ask them about (in fact, even in the US, asking friends about them would have been not straightforward). But there was no risk for these strangers, because I was one, too. And not only that, I also was an outsider, someone completely outside of the norms they had to live with. To paraphrase a different idea, what is proper is proper until it is no more.

Throughout the years, Sophie Calle has subjected strangers to her unbounded curiosity, whether with their consent or not. Inevitably, the ethics of doing it enter immediately. It’s one thing to invite strangers to tell you a secret to then bury it (or hide it in a safe). It’s quite another to find someone’s address book and to then not only call the people contained therein but to also write about it in a newspaper. In the end, this approach is testing a viewer’s/reader’s boundaries: how far would I go? What do I feel is proper?

Unfortunately, with ethics being ethics and strong feelings seeking an outlet, Calle has opened up herself to quite a bit of abuse. A male artist might have got away with the address-book idea more easily than a female one (there is, after all, that rather primitive idea of male bravado). Henriette Huldisch discusses this aspect at length in her essay.

This is not to say that all of Calle’s projects were ethically solid (the artist appeared to have realized as much after The Address Book). Yet, I maintain that there is much to be gained from probing the boundaries of what is proper, in particular when you include yourself in the work. I feel that this aspect or art making is criminally underdiscussed in the world of photography, where too many photographers too strongly believe in their privilege as the person in charge of the camera.

As a brief aside, this does not mean that including yourself automatically makes work OK. For example, Antoine d’Agata’s work will forever be tainted by the artist’s broken moral compass, regardless of how many times the photographer puts himself in front of his camera.

The key to probing boundaries is to be aware of them and to be aware of the transgression. This entails acknowledging other people, and it involves empathy (d’Agata’s work is failing on all counts here). For me, Calle’s work is strongest where transgressiveness and empathy both play a very important role. Where one is noticeably absent, things don’t quite take off — or they take the wrong turn. That’s why, for example, The Sleepers is so much stronger (in all kinds of ways) than The Address Book.

But is there a Sophie Calle? Is it a good idea to treat the person behind the many different bodies of work as the exact same person (as I did when I thought about Voir La Mer)? Or rather, can we distinguish different phases (if we want to use that word) in this artist’s career that might differ from each other — and if yes, what might those differences be?

Overshare solves that riddle through chapters (“The Spy”, “The Protagonist”, “The End”, “The Beginning”), which does the trick — or rather a trick. The problem with organizing an artist’s work through their artistic strategies is that you introduce a strong reductive element into things. Obviously, for an exhibition to work you will need some organization, especially if an audience (here in Minnesota) might not be very familiar with the artist in question. (If Tim Waltz was right with his “mind your own damn business” spiel, the Minnesota audience will experience the very opposite of it.)

Still, I feel that the rather simplistic chapters undermine some of the spirit of Sophie Calle’s work, larger parts of which were done with that wink towards the people whose lives were being put under a microscope — and towards the audience that simultaneously is told that they’re in on the joke, while somehow being made to feel uneasy about that very fact.

Regardless, while I stopped maintaining the illusion that the world of photography (outside of her native France) will suddenly realize how much Sophie Calle has to offer, there still is that shimmer of hope. And here’s a new book, a very nice overview with some essential pieces, some well known, others less so. You might as well have a look!

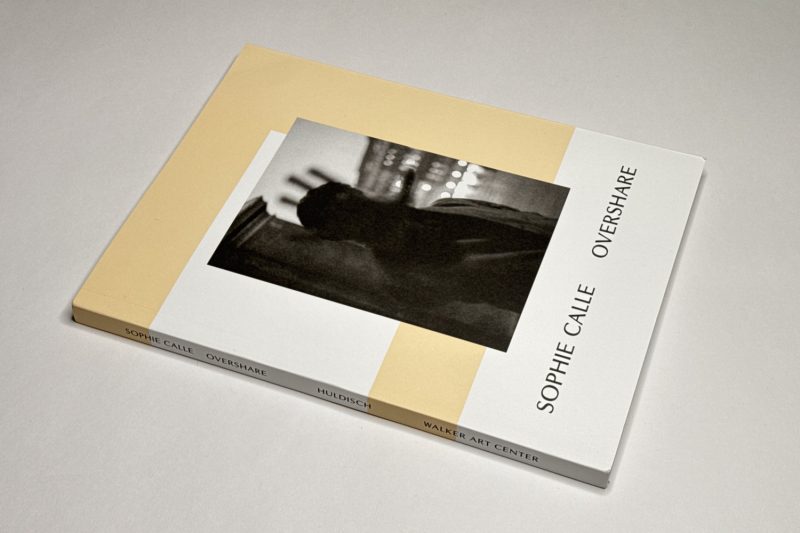

Sophie Calle: Overshare; edited with text by Henriette Huldisch; text by Mary Ceruti, Eugenie Brinkeman, Aruna D’Souza, Courtenay Finn; 200 pages; Walker Art Center; 2024

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing to my Patreon. There, you will find exclusive articles, videos, and audio guides about the world of the photobook and more. For those curious, there now is the possibility of a trial membership for seven days.

Much like journalism, photography criticism involves a huge investment of time and resources. When you become a subscriber, you not only get access to more of my work. You will also help me produce it (including the free content on this site).

Thank you for your support!