It is one of the terrible ironies of modern medicine that sometimes, it has to destroy the body in order to heal it. Cancer might be the most commonly known situation to arise that typically ends up in that territory, a disease that is more common than we possibly might want to admit to ourselves. Fortunately, I have not been at the receiving end of such treatment, and I hope I never will be. But I suspect that much like anyone else, I know people — family members, friends — who have (a relative was just diagnosed with a brain tumor). Some made it through alive while others unfortunately did not.

What makes medical emergencies particularly difficult is that while suffering can be communicated, it cannot be shared. I am unable to feel your pain, and you are unable to feel mine — at least in a literal sense. This is a situation that pops up in photography all the time: while cameras are very good at recording surfaces, they are unable to depict emotions or feelings. Even as being empathic might allow a viewer to get a sense of another person’s suffering, there is a limit to that. (If there weren’t, photographs would have long stopped wars.)

Consequently, the best photography produced around suffering and illness uses metaphors instead of attempting to hammer home a point. Metaphors will only get you so far, of course. But we already know from the history of photography that pictures will not do what we want them to do if the direct route is being taken. Metaphors, in contrast, offer the promise of lighting up the imagination. They might make us think in ways that gruesome, direct depictions of violence or suffering are unable to.

In Outside Room 8 by Lotte Bronsgeest and Geert Broertjes, photographic materials are made to undergo the same treatments as the human body, specifically Broertjes’. After Broertjes had been diagnosed with colon cancer, Bronsgeest, a friend and colleague who was already working on a similar project (the two met as students at an art school), asked him whether there was a way to produce work together about what his body and mind was about to undergo.

Consequently, Bronsgeest not only photographed her friend. A number of photographic materials were also subjected to the same treatment that a human body might be subjected to during cancer treatment: radiation and toxic chemicals (“chemo”). In essence, larger parts of the project became process based. I’ve had my qualms about process-based work because typically, the process itself tends to draw a lot of attention to itself. But here, that’s exactly the point, and that fact has me very interested.

Outside Room 8 presents a large number of images made by Bronsgeest and Broertjes, which includes not only process-based pictures but also “straight” photographs and medical images. Visually, this makes for an intriguing and at times disconcerting viewing. Given that the book’s topic is established quickly, this viewer found himself being thrown back and forth between simply enjoying some of the abstract beauty and trying to make sense of it, trying to understand how human tissue might be affected when treated the same way as the photographic materials. If that was the idea of the work, it’s communicated very effectively.

Part of what makes the work interesting is the breadth of the images. Were they all uniformly distorted, the effect would quickly become predictable. Here, it’s never clear what comes next, which helps convey a sense of uncertainty. What’s more, some of the imagery is simply beautiful.

I usually detest the triteness of the sentiment that beauty can be found everywhere because too often, it’s used to paper over suffering and preventing oneself to engage more deeply (and honestly) with a challenge. I don’t see that sentiment at work here. Instead, the unexpected beauty that can be found in the book confounds expectations and helps the viewer to engage with it more deeply.

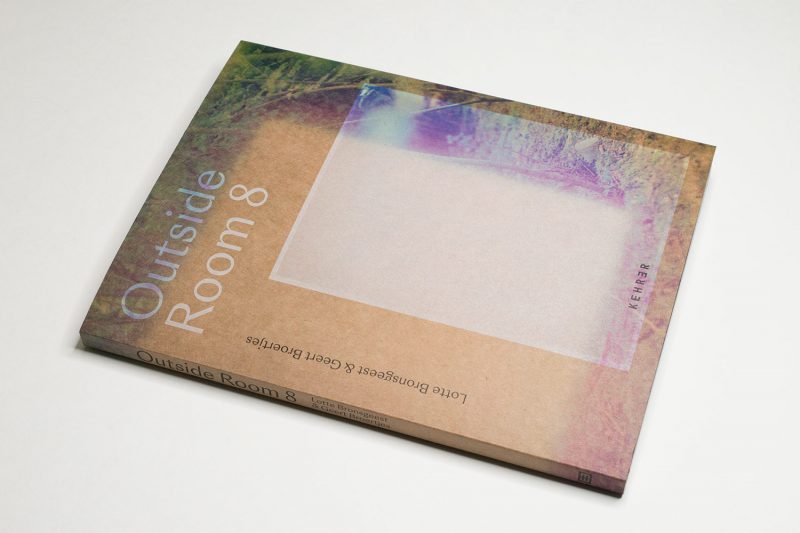

The book incorporates some design and production choices to deliver its message. Most notably, it uses pouch pages: the paper is folded at the fore edge and bound (glued) at the spine. Of late, this type of binding has become slightly more common in the world of the photobook, given that you can include material inside the pouch itself. The makers of the book did employ that trick. I ended up being slightly confused about whether or not I am supposed to cut open the pages or not. I ended up not doing it. That aside, the production of the book is absolutely impeccable — if you pay careful attention, you’ll see selected spot varnishing, a long gatefold, and more.

All of that combines to make Outside Room 8 a really interesting book that demonstrates that process-based photography is able to tackle very profound topics in a deeply meaningful manner. A very handsome production, it showcases the beauty of what can be achieved when such work is put into the context of the contemporary photobook.

Outside Room 8; photographs by Lotte Bronsgeest and Geert Broertjes; text by Lotte Bronsgeest, Geert Broertjes, Theun van der Heijden, and Jelle Bouwhuis; 128 pages; Kehrer; 2022

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing to my Patreon. There, you will find exclusive articles, videos, and audio guides about the world of the photobook and more.

Much like journalism, photography criticism involves a huge investment of time and resources. When you become a subscriber, you not only get access to more of my work. You will also help me produce it (including the free content on this site).

Thank you for your support!