There is a very telling anecdote in Robert Slifkin‘s excellent Quitting Your Day Job: Chauncey Hare’s Photographic Work. “Such was the power of Hare’s singular vision,” Slifkin writes near the end of the book (p. 215), “that […] his mother resisted having her portrait taken by him for fear that she would look like all of the other characters in his pictures.” The source for this is a tape that the photographer produced himself, a recording of a conversation he had with designer Marvin Israel around the time of his first and only exhibition at MoMA.

It is relatively easy to spot a photograph by Chauncey Hare, in particular one of the peopled interiors. Typically, one or more people are depicted in what through the use of a wide-angle lens looks like a cavernous, barren room. More often than not, the scene is harshly illuminated by a flash. At times, some of the subjects in a picture are posing for it, while other are not. Some of Hare’s sitters were unaware of the wide-angle lens so they simply assumed that they wouldn’t end up in the picture.

Today, Chauncey Hare would be a well-known name in the world of photography, much like, one suspects, Diane Arbus, Lee Friedlander, or maybe Allan Sekula. But he is not. There were three books made during his lifetime, two of which I own. The first — Interior America — was published by Aperture at the occasion of the aforementioned MoMA exhibition in 1977. The second book — Protest Photographs — was published by Steidl in 2009. They’re both out of print. For a number of reasons, Interior America is the vastly better book. Hare’s third book — This Was Corporate America — was self published in 1984. By that time, Hare had completed his withdrawal from the world of photography almost completely.

There’s something very interesting about Hare’s photographs. You could crop parts of some of them, to arrive at a different photograph’s picture. Often, a single photograph will allow for more than one such crop. I can’t easily think of another photographer that includes, say, a Diane Arbus picture alongside a Walker Evans. This is not to diminish the quality of Hare’s work — on the contrary. I think that Hare was a more interesting photographer than (to stick with my example) both Arbus and Evans. He was able to combine an incredible skill at composition (with some very minor staging thrown in) with highly charged portraiture.

Much like in the case of Arbus, there’s a deeply unsettling aspect to Hare’s portraiture — exactly the thing his own mother picked up on when she declined to be depicted. In the photographs, people typically come across as being completely lost in the cruel and unforgiving world of their own homes, when they don’t look like Arbusian characters. It’s not clear whether Hare was aware of the fact that his portrayal of people could be seen as abusive, even as he set out to show with them how they were being abused by corporations.

I’m writing these words as someone who has long admired Hare’s work. Over the years, I have come to the realization that good photography (or maybe photography that manages to reach the level of art) does not offer a single path towards what it might mean. In good photography, there is more than one element. The combination of the different elements creates a push and pull for the viewer, having them face conflicting emotions.

(For a long time, I thought Arbus possessed this element. But now, I think the pictures merely reflect their maker’s cynicism and cruelty. There’s the push, sure. But the pull viewers end up having to construct for themselves: nobody wants to admit that much like Arbus, they’re fascinated by visually sneering at people.)

There’s an agenda behind every photographer’s work, even if some (possibly many) of them would like you to think that’s not the case. Hare was upfront about his. In fact, any time you see a photograph of his today (which is very, very rare) it comes with the disclaimer. In the list of image credits in Quitting Your Day Job, the disclaimer can be found after each of Hare’s pictures. It reads in full: “This photograph was made by Chauncey Hare to protest and warn against the growing domination of working people by multi-national corporations and their elite owners and manager.”

How or why this makes sense (or not) is brilliantly laid out by Robert Slifkin in Quitting Your Day Job, which might be re-setting the standard of what a photographer’s biography actually ought to look like. It balances criticism with admiration. It presents the photographer as the kind of conflicted human being that we all are. This is a much needed deviation from the hagiographic attempts of biography produced for a number of famous American photographers recently.

I suppose in many ways, Hare made this easy: he had quit the world of photography in ways that decades later left strong recollections with a great many people. In fact, it would be tempting to view Hare as a strange interloper (in my own experience, I’ve noticed how photoland loves these kinds of people — they’re part of the system but, intriguingly, they’re not). While you could certainly think about it this way, the care and attention that Slifkin devoted to Hare and his work resulted in a book that goes very deep into this man’s life work and that indirectly also comments on the world of photography itself.

Throughout the book Slifkin manages to remain accepting of Hare’s predicament, even as he details the many, many unusual events that happened during the time when Hare was considering himself a photographer. Told out of context, some of them are too strange to be true. Did Chauncey Hare actually picket an exhibition at SFMOMA that he was included in, severely damaging his prospects of future engagement with the museum? Yes, he did. But there are a lot more details here (and elsewhere) that are worthwhile knowing.

What struck me when reading the book was how Slifkin managed to strike the perfect balance between being sympathetic to Hare’s ideas and aspirations and laying out all the details of the various conundrums and problems created by a photographer who found himself at odds with the world around him more or less all the time. In a nutshell, Hare must have been an incredibly difficult person who appeared to have lacked the understanding that human relationships of any kind are impossible without a degree of compromise. I’m thinking that these are the perfect ingredients for great photographs and great trouble.

Hare had started work as an engineer for the company that is now known as Chevron (previously SOCAL), possibly the kind of job that would have set him up for a comfortable life. But he was deeply unhappy in that job and had found that photography offered him an outlet. Through sheer determination, he managed to produce photography that was so good that it easily competed with what was being fêted by John Szarkowski, the most well-known and most powerful curator at the time.

After his MoMA exhibition, Hare pursued an MFA. Attending San Francisco’s Art Institute, he studied with teachers such as Sekula, Martha Rosler, and others — even as, the book makes clear, Hare clearly didn’t think he needed to learn anything. He wanted the MFA to be able to teach. The book dives into these aspects as well, much as it covers, say, Hans Haacke’s institutional critique, which could have easily provided a framework for the direction Hare was heading in (with his inclusion of text and audio materials in exhibitions).

I’m now thinking of Hare’s photographs as the missing link between American photography as established by Walker Evans and the photographers that ended up being lumped together in the New Documents movement. As I already noted above, Hare managed to charge most of his pictures with elements of both. The combination makes the results more interesting than either the older or Hare’s contemporaries’ work. The contradiction between two impulses creates the sparks: it’s not either blank description or slightly cynical (and possibly sneering) observation at arm’s length — it’s both at the same time. What a combo!

However, as Slifkin writes (p. 127), “MoMA […] was just as much corporate entity as SOCAL (one, moreover, that had shared origins in the Rockefeller family), and the museum seemed to propagate many of the same oppressive practices that made his experience as an engineer so frustrating and at times nauseating.” In Hare’s own words (p. 126f.): “I couldn’t tell any difference between Szarkowski and some person at Chevron who is about three levels above me. The same kind of authoritarian outlook.” Within the logic of his own mind, there could only be one conclusion, one possible way to deal with the situation he had placed himself in.

“Hare’s disavowal of photography,” Slifkin observes (p. 188), “wasn’t so clearly an act of willful renunciation as much as one of disheartened resignation.” If you want to take anything away from this biography, it’s this. Hare deeply loved and cared for photography. But the world of photography was unable to love him back on the terms that he wanted.

It was, in Hare’s words (p. 159), a “playground for the rich”, filled with people who are “seeking personal recognition above any responsibility to themselves as complete human beings.” He followed through on what he believed in and eventually ended up becoming a therapist.

Hare had, in Slifkin’s words, “sought — and in many cases succeeded — in rendering the world in his photographs as an extension of his interior self.” It’s just that in his particular case, the photographer’s interior self was unable to deal with the fact that while the world of photography loved the world in his photographs, the world in his photographs was incompatible with the world of photography.

Very highly recommended.

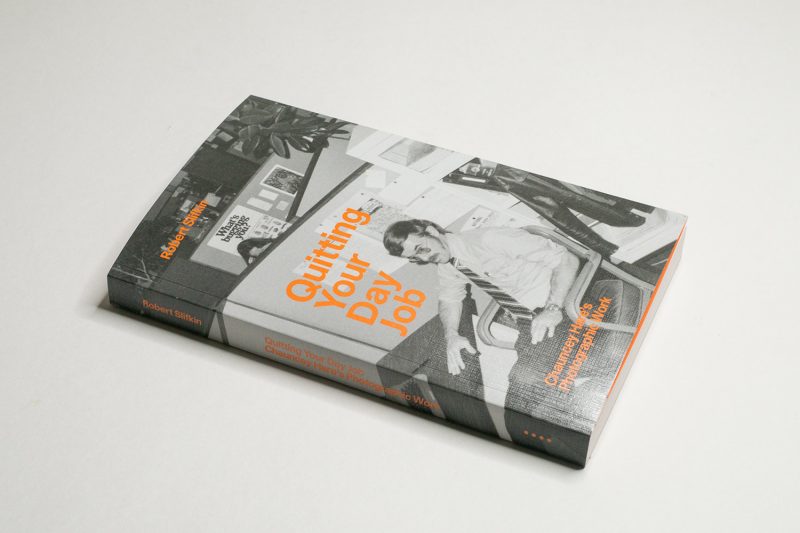

Robert Slifkin — Quitting Your Day Job: Chauncey Hare’s Photographic Work; 242 pages; MACK; 2022

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing to my Patreon. There, you will find exclusive articles and videos about the world of the photobook and more.

Much like journalism, photography criticism involves a huge investment of time and resources. When you become a subscriber, you not only get access to more of my work. You will also help me produce it (including the free content on this site).

Thank you for your support!