A 1989 publication entitled Hollandse Taferelen (Dutch Scenes) by Hans Aarsman presents the authors views of his home country through a combination of photographs and text. Photographically, the book is very much a product of its time, with the view-camera images referencing more widely known bodies of work, whether (mostly in process) Joel Sternfeld‘s American Prospects or (in the spirit of the work) Joachim Brohm‘s Ruhr. Much like Brohm’s portrait of parts of Germany, Aarsman’s portrait of Holland reveals a rather unremarkable place being made utterly remarkable. In a sense, Aarsman’s views of the country are much more true to it than any tourist brochure could be (but then, they do make for very bad tourist-brochure material).

In a country as educated as the Netherlands, with its long and widely shared artistic and cultural tradition, I suspect that these 1989 scenes would have not necessarily be seen against either Sternfeld or Brohm. They would have been seen against the long history of portrayal of the country over the whole course of art history. Aarsman’s photographs are completely unlike Dutch Golden Age Landscape Paintings. But ignoring media and styles of portrayal, I think the spirit of these works is very much the same: artists celebrating this fragile part of the world which is constantly threatened by the sea not only for what it is but especially for how it reflects the lives and efforts of those living within it.

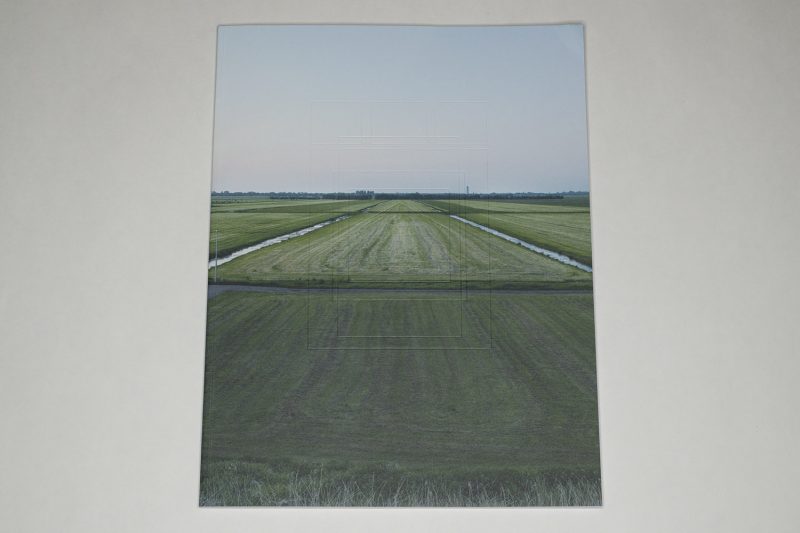

Marwan Bassiouni‘s New Dutch Views follows this tradition. To write that it does so with a twist is both correct and not correct. It is correct because the Dutch views each are part of another view, one in which the interiors walls and windows of mosques are visible. It is not correct because the inclusion of who is looking at the land might have been made explicit — but isn’t all art made from a particular view point? To insist that there’s a twist might just reinforce the very separation the book in my mind works so hard against, namely the one that divides those Dutch citizens who happen to be Muslims from all the others.

I can think of at least two immediate reads of the work. The Dutch views present the land outside of a very specific environment, the mosque. I’m alternating between reading the work as aspirational, as wanting what is inside these buildings to be an integral part of what is visible outside, and reading these photographs as an expression of a frustration, a frustration arising from the feeling that the inside and the outside might not be easily reconcilable, given societal and political circumstances.

A country like the Netherlands is embedded in a larger geographical region — Europe — that is no stranger to the persecution of religious minorities. To pretend that Islamophobia is anything other than yet another variant of any of the various religious follies that have wrecked the continent for the past two millennia is disingenuous. The various neofascists pretending they’re aiming to protect the values of whatever countries they’re from — in the Netherlands, you’d have Geert Wilders — are not doing that. Instead, they’re following a tradition that has led to the deaths of millions of people over the course of Europe’s history.

But the toothpaste has long been out of its tube anyway: Islam is a part of the Netherlands, just like it’s a part of Germany and many other European nations. This then would be the third read of the work, the read that in the ideal world that we don’t live in would be the only one, the obvious one: these pictures happen to show what the Dutch landscape looks like from the windows of mosques. The aspirational read, the frustrated read — they are caused by the politics inserted into our societies.

As is the case with most photography, it’s really the context that provides the fuel that drives a work’s power. These photographs are powerful and challenging because they assert what ought to be the case, given the constitutions of Western nations, but what is being challenged on a daily basis by neofascists and also many conservatives, namely that all people are equal, regardless of their gender, sexual orientation, religion, political orientation, or whatever else. The photographs do what they do because of what we bring to them when we see them. In other words, they make us react, and we better pay attention to how we react to them: we might learn something about ourselves.

The book contains some added text in the form of short fragments that are hidden inside the pouch pages. The pages haven’t been trimmed at the top, so the interiors of the pouch pages are easily accessible, but they don’t present themselves right away. With these fragments, Bassiouni expresses his own sentiments and ideas, covering his upbringing and identity. This adds another element to the book, a human voice that will help the viewer get a better understanding of the photographs on view.

With so many complex, narrative-driven photobooks having emerged recently, I’m enjoying seeing one that tackles a complex subject matter as simply and beautifully as New Dutch Views does. With just a few basic devices employed (also for the design and production of the book), it demonstrates the power of the photographic book.

New Dutch Views; photographs and text by Marwan Bassiouni; 64 pages; Lecturis; 2019

Rating: Photography 4, Book Concept 4, Edit 3, Production 4 – Overall 3.9

Ratings explained here.